Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Jack Cockerill was working for the Chester Diamond Drilling Company when he was engaged on a contract at the Leicester Mine, on one of the kimberlite pipes found on the farm ‘Holpan’ between Windsorton Road and Barkly West in the Northern Cape. He was housed in bachelor quarters on the farm and came into contact with the family of Willie Wienand, who was in the cartage business in the area. Romance blossomed with Willie’s daughter Gladys May Wienand, and Jack became attracted to the lifestyle of alluvial diamond digging. He left Leicester Mine, applied for a digger’s licence and set up on his own dig. This account of Jack’s life as a digger was written by his daughter, Judy, and is part of our family history. [Olwyn Garratt]

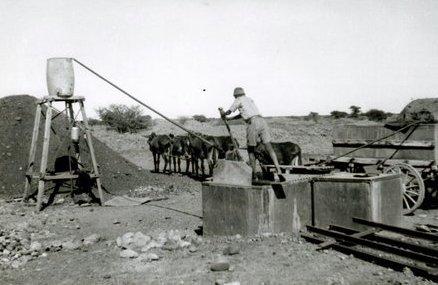

My Dad’s diggings were on a farm belonging to Mr David (Dawie) Wright. The area was proclaimed and diggers had to be of good standing to be considered eligible to be granted a licence. The Holpan diggings were not deep and they did not require a mining inspector to approve them. Although they were loosely termed alluvial diggings they were not on a river and the water required for the running of the washing plant had to be brought in by donkey wagon and stored in a tank on a raised platform.

Donkey cart bringing water

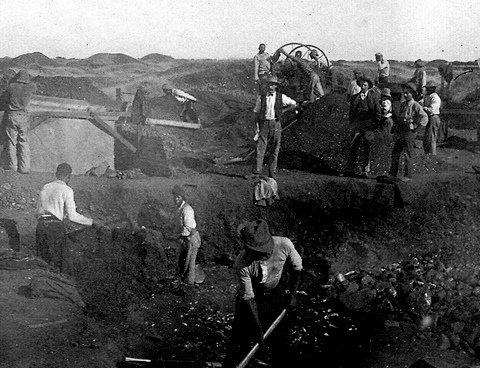

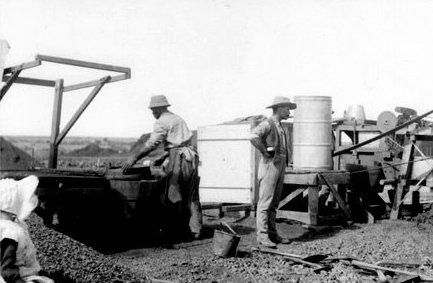

Dad had a gang of about 20 labourers who lived in a nearby settlement. The men dug with picks and shovels and loaded ground into a large bucket.

Diggers

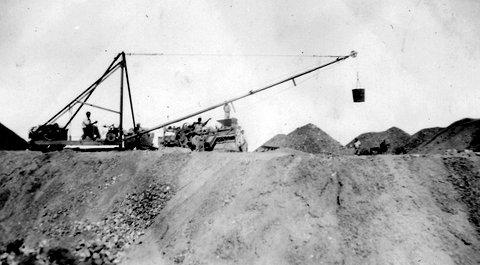

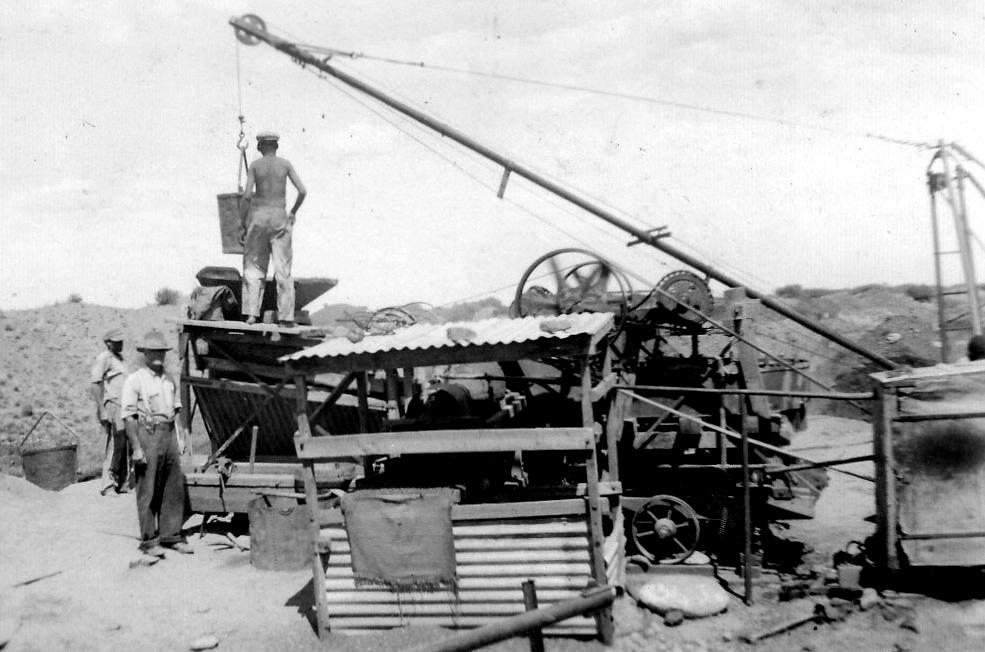

Lifting gear was mounted on a large frame fitted with two wheels to enable it to be transported from one site to another. The bucket was raised by an engine-driven crane and the gravel dumped into a hopper.

Lifting gear

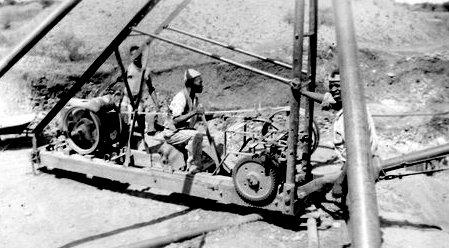

Crane operator

The heavy material in which diamonds were found consisted mainly of banded ironstone pebbles that were called bantoms, from the Afrikaans expression ‘bandom’. The early method of separating bantoms from tailings was a slow process. A gravitator comprised a large sieve which was bounced up and down by hand or by means of a cam. This sieve was suspended in a mixture of water and sand of such consistency that the light gravel or tailings floated over the sides, leaving the heavy material or wash to remain in the sieve. The sieve was slightly inclined and the wash gravitated through a small chute leading to a hopper from which the heavy material was periodically drawn off. It was in the heavy material that the diamonds were found.

Separation of material. Judy as a little girl in sun bonnet coming to watch her father managing his claim.

Later the jigger baby was used. It was thought that this was named after its French inventor, Bèbè, an oscillating sieve fitted with two sizes of mesh which caused fine sand to fall to the ground and coarse material larger than a fist to be rejected. From the hopper the ground was fed into the jigger baby and the ground which contained the bantoms was then tipped into a circular pan with a sludge mixture. In this pan a series of six arms fitted with teeth set at special angles traced a spiral pattern in the puddle of water and sand that pushed the heavy material to the outer edge of the large flat pan from which it was periodically drawn off. The tailings overflowed in the middle of the pan and over a sieve. The puddle was recovered and lifted back into the pan together with new gravel that was to be sorted.

The heavy ground went through a washing process before being tipped onto the sorting tables.

Sorting tables

The scourge of the diamond industry was illicit diamond buying (IDB), and Dad undoubtedly lost a great deal of money when his labourers sold their finds to a neighbouring digger instead of handing them up as was expected. In 1927 he accompanied Sir Ernest Oppenheimer on a trip to Port Nolloth to investigate the situation surrounding IDB and subsequently he became involved with the Board of Control regulating the affairs of alluvial diamond diggers. He was one of principal parties to a memorandum presented by the Board to the government, which had the effect of amending anomalies in the Precious Stones Act.

Dad had a wonderful command of the English language and over the course of time he was able to speak at gatherings without hesitation. The diggers began to organise themselves into committees and Dad came to be recognised as their spokesman, particularly during consultations with the minister of mines.

When the Prince of Wales visited South Africa in 1925 he paid a visit to the Kimberley diamond fields. He was taken to Barkly West at the invitation of the mining commissioner and it was Dad who was chosen to present the illuminated address to his royal highness on behalf of the digging community.

The Depression years were very troubled times for the diggers, and after struggling for a time Dad was forced to sell his gear, ending a fascinating chapter in his life.

Olwyn Garratt enjoyed a long a fruitful career in law librarianship. In recent years she done priceless volunteer work at the Transnet Heritage Library in Johannesburg. You can contact her using this address - olwyn.garratt@gmail.com

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.