Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

There are a number of basic principles to be followed when an Imperial or Colonial army equipped with superior firepower takes on a so-called “native” or indigenous enemy armed principally with hand-held weapons such as spears, clubs, swords etc. One of these is to be able to shoot the enemy before he can get close enough to use his own weapons.

In this event, although it might look very precarious, the situation is actually quite under control and there is little or no danger posed to the side with the superior firepower.

So long as the ammunition keeps coming! Fire control and re-supply is therefore critical.

Fire Control

Grierson in Scarlet into Khaki states:

The usual deep formations of infantry are not advisable in war against savages; on the contrary, the front rank (line of riflemen) must be powerful enough to repulse all hostile assaults by their own strength. In the Zulu War a detachment was annihilated at Isandlwana, because the endeavour was made to resist an attack of the enemy in loose order. The infantry will mostly remain in close formation, and to advance steadily so as not to weary the men uselessly, and to maintain order. Special stress is to be made on fire discipline. The firing is exclusively by volleys and at short distances. What the savages dread most is a bayonet charge.

Volley firing would have been done by section, not en masse. There was therefore no requirement for individual marksmen to take pinpoint shots – the British relied on the weight of fire rather than the accuracy.

Rapid Fire

Statistics from the battle of Kambula suggest that each British soldier, somewhat surprisingly perhaps, fired an average of less than 40 rounds during the three or so hours of hectic engagement. Contrary to popular American war-movie myth, then, weapons do not fire hundreds of rounds per minute for hours on end without magazines having to be re-charged or barrels melting. Victorian “Rapid Fire” was, in this instance, approximately a paltry 10 rounds per man per hour.

Ammunition re-supply

Grierson describes the logistics of ammunition re-supply as follows:

In battle every half-battalion is followed by an ammunition cart and a mule; the animal is placed between the supports, the cart behind the reserves; the other two carts of each battalion are combined to form the ammunition reserve of the brigade, and follow behind the second half of the brigade in charge of a mounted officer. In every company 1 non-commissioned officer and 2 – 3 privates are told off to bring and distribute the ammunition.

Before the commencement of the engagement 50 cartridges are to be taken out of the ammunition cart for each man, so that each one is supplied with 150 cartridges. During battle cartridges must be sent to the front at every opportunity. In every cart there are a number of sacks (each containing 300 cartridges), two of which sacks can be brought up by each ammunition carrier. The carriers stop with their companies, and subsequent relief must come from the companies of the reserve. It is the duty of the non-commissioned officers to see that the cartridges are taken from the dead and wounded. Although the regulations proscribe that the ammunition should be brought to the front by men, yet the ammunition carts and mules must be pushed forward as much as possible. On ordinary ground the former must stand at a distance of 1000 yards; the latter at 500 yards from the line of skirmishers; in wooded or covered ground the distances are to be still less.

Tactics

Once again we return to Grierson:

In defence it is calculated that to occupy a fairly strong and partially entrenched position; there are required for every pace of ground 5 men of all arms, inclusive of reserves. The troops are grouped into three Lines (skirmishers, supports and reserves) as is done in delivering an attack. The first Line forms a line of skirmishers as close as possible, divided into sections, with local supports and reserves, and it also sends out men to occupy advanced posts, if any. The second Line protects the flanks with troops carefully placed under all available cover; it stands ready, jointly with other spare troops, to support the first Line, or to carry out counter-attacks. The third Line is drawn up in a position, whence it can assume the offensive with greatest effect; as soon as the attack is fully developed. The troops in the first Line must be kept well supplied with ammunition, and communication must be kept up by flag signalling.

Ammunition Expenditure / Kill Ratio at Isandlwana

It is impossible to estimate the ammunition expenditure / kill ratio at Isandlwana. There are simply too many variables in play.

Current estimates are that some 1 357 British and Colonial troops lost their lives there. Zulu casualties are unknown. This figure was originally put at 1 000, since the British estimated that they should have killed at least one Zulu for every lost soldier. On second thoughts, though, that figure was bumped up to 2 000 so as to give the impression of an “honourable draw”. It was later bumped up again to 3 000, on the basis that Cetshwayo is reputed to have said that Zulu casualties were so heavy that “there were not enough tears to mourn for the dead’ and that figure made the British effort appear a little more professional.

So, then, how many Zulus died here? Was it 1 000, 2 000 or even 3 000 or anything in between? How many survivors subsequently succumbed to their wounds? Due to the lack of written empirical evidence recorded by the Zulus, It is anyone’s guess.

Ian Knight in The Sun Turned Black states:

Shortly after Mostyn and Cavaye’s companies had retreated to the bottom of the hill, Essex observed that they were “now getting short of ammunition, so I went to the camp to bring up a fresh supply. I got such men as were not engaged, bandsmen, cooks etc. to assist me, and sent them to the line under an officer, and I followed with more ammunition in a mule cart.

Smith-Dorrien, who could well have been “the officer” described by Essex, said in his memoirs that:

I, having no particular duty to perform in camp ... had collected camp stragglers, such as artillerymen in charge of spare horses, officer’s servants, sick etc. and had taken them to the ammunition boxes, where we broke them open as fast as we could, and kept sending the packets out to the firing line.

There is a bit of an anomaly here. Knight states that each soldier carried 70 rounds on his person, with 200 spare in the ammunition wagons. Grierson states that the soldiers had access to 150 rounds per man, with sacks containing 300 rounds of ammunition in reserve. These were to be brought, two at a time, to the front by troops or by mule-cart. That notwithstanding, there is consensus. Once the carriers had gone forward, it was up to the reserve troops to assume the duty of carrying ammunition forward, which was precisely what Essex and Smith-Dorrien were doing.

The system of ammunition re-supply was obviously in place at Isandlwana. There is therefore nothing to suggest that the troops ran out of ammunition. They may have run short, in some instances but not necessarily run out. If Grierson is correct, even at a conservative estimate of a total of 150 rounds per man, multiplied by, say, 1 000 men, the British should have had access to at least 150 000 rounds.

So, then, thus far we can see that the rifle was fine; the bayonet was fine, the ammunition was a man-stopper and the British had enough of it. The British purposely chose Isandlwana as a suitable defensive site. The Zulus approached from the front, in full view and uphill, giving the British reasonable time to prepare.

That being the case, it would seem that most of the men at Isandlwana should have had enough ammunition on them to last through the main battle, which was over and done with in under two hours.

It would be incorrect to assume that all of that ammunition was expended. Much of it would have been dropped in haste, fallen out of open ammunition pouches as soldiers changed position, lost in the wagons, or captured by the Zulus. It is therefore impossible to even begin to estimate how many rounds of ammunition were fired by the British and how many were left over.

It is also not possible to give an accurate figure of Zulu casualties at Isandlwana. How many were shot? How many fell to the bayonet? How many died in hand-to-hand scuffles? How many crawled away to die later of their wounds? Therefore the exercise of determining ammunition expenditure and kill ratio at Isandlwana is meaningless.

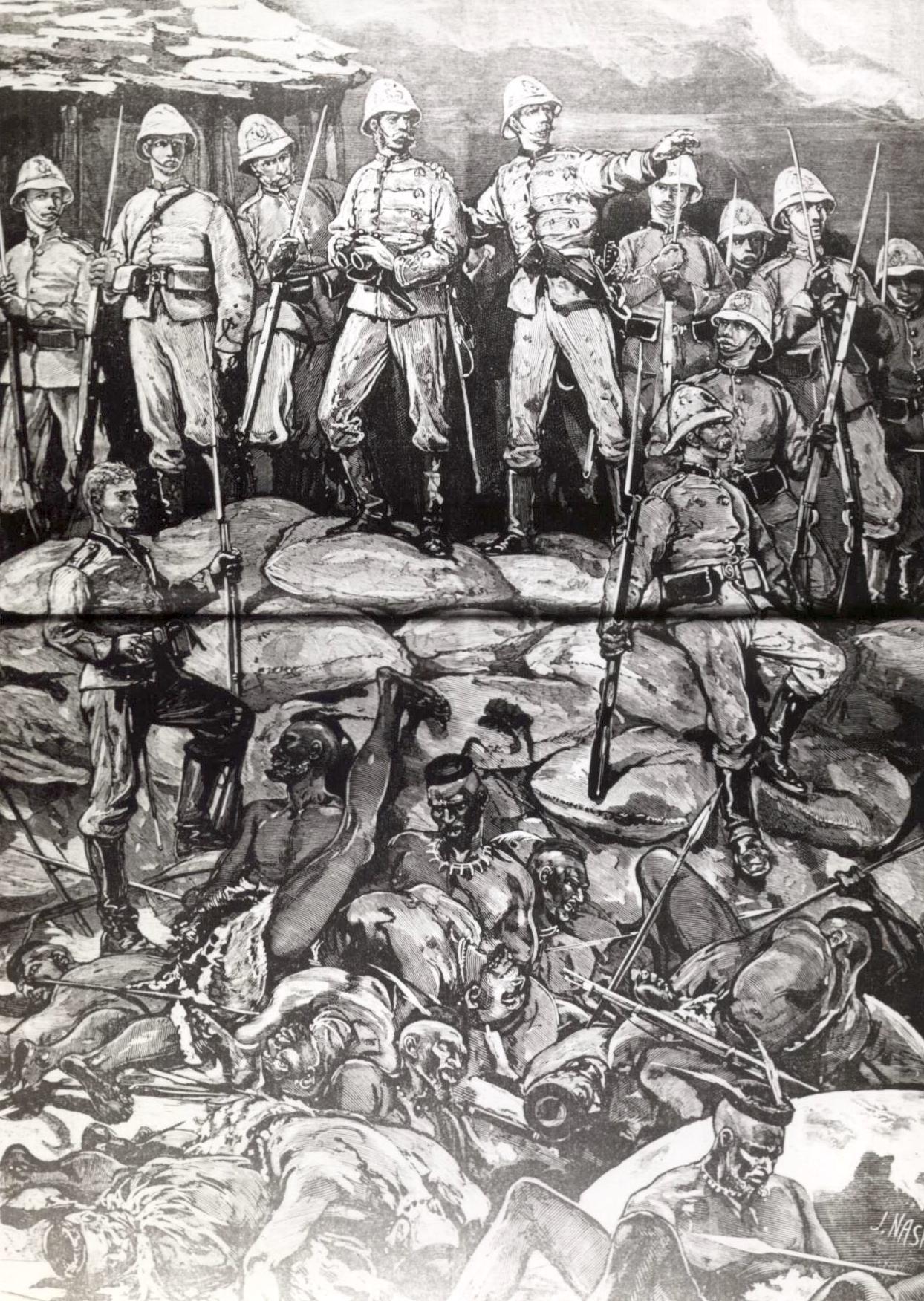

Paintings of the Battle of Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

Ammunition Expenditure / Kill Ratio at Rorke's Drift

Here, we appear to be on safer ground. Most of the defenders survived. Witnesses were therefore not in short supply. Records were kept and lovingly analysed for years. It must be said, though, that these records are obviously very one-sided.

The temporary Commanding Officer at the Drift, Lieutenant John Rouse Merriott Chard RE, wrote a detailed account of the exploits of the garrison there, which has become the cornerstone for any subsequent analyses and publications.

According to Chard, some 351 dead Zulus were buried after the battle. This figure is considered correct as the British kept meticulous records. Subsequently, other sources have bumped this up to an arbitrary 500, arguing that an additional 150 Zulus or so would have managed to walk away but later died of their wounds.

British casualties, again well documented, amounted to 17 men, two of whom can be discounted as one was a deserter shot by his own people, and another a so-called “native patient” allegedly killed in the hospital.

A score of 351 to 15 represents quite a remarkable achievement.

It was a close-run thing, though. After a 12 hour battle, Chard reported that the garrison was down to a box and a half (900 rounds) of ammunition and that one more Zulu charge would have done it. However, at that point, for reasons still unexplained, the Zulus called it quits and marched away.

Rorke’s Drift was the forward supply base for the newly annihilated British Column at Isandlwana, and thus had a reserve stock of 20 000 rounds of ammunition. If one deducts the “box and a half” left over, then British ammunition expenditure was 19100 rounds plus each man’s front-line allocation of 70 rounds, which totalled another 9800 rounds.

If one accepts these figures, then, almost 29000 rounds were fired by the British during the battle of Rorke’s Drift.

At least 351 Zulus died.

15 British and Colonial troops died.

The British garrison numbered 141 men, of whom 36 were patients in the makeshift hospital. Zulu numbers are estimated at about 4 000.

On analysis, however, a very different picture emerges from the traditional one of stout-hearted Tommies beating off attack after attack of thousands of blood-crazed savages charging up and down the barricades in unceasing waves.

Painting of the Battle of Rorkes Drift (Talana Museum)

Given that the battle lasted some 12 hours and that the British lost 15 men that they cared about, if one divides the one by the other, then the Zulus killed just over one man in the entire garrison per hour.

If one takes 351 dead Zulus and divides by 141 defenders, then each British soldier killed, on average, just over two Zulus, or one every six hours.

If one takes 29 000 rounds of expended ammunition and divides that by 351 dead Zulus, each Zulu death required, on average, about 80 shots.

A number of conclusions may be drawn from these figures:

- British casualty per hour does not amount to much of a fight.

- Zulus killed by each British soldier on average over a 12 hour period doesn’t amount to much of a fight either.

Therefore the battle of Rorke’s Drift was not an unceasing pitched battle involving thousands of men at a time, but a series of intense little skirmishes followed by long periods of inactivity.

The fact that only 1 British soldier died, on average, every hour, tells us that –

By and large, British strategy worked. They simply did not allow the Zulus to get close enough to use their main battle weapons for most of the time, but shot them down outside that magical spear-throwing range.

When the Zulus did get close on occasion, they found that the British were well protected by buildings and barricades and their only point of entry into a building was through the doors or windows. In that situation, overwhelming numbers don’t count for much. Only one man can get through the door at any one time while the rest bunch up in a heap outside. In this event, superior numbers actually work against you.

Of the 15 British dead, 4 were shot, 8 were stabbed and the other 3 suffered “unknown” causes of death. Of the 13 men wounded, 10 were shot and only 3 stabbed. This gives one a ratio of more British killed or injured by gunfire rather than stabbings. In other words, apart from the intense activity during the first two hours in the hospital, Rorke’s Drift developed into a fire fight, with Zulus unable to approach close enough to use their spears. It is now accepted that the Zulus had access to approximately 20 000 firearms of varying quality at the beginning of the War, plus whatever they had managed to loot at Isandlwana. It is quite conceivable that they could have engaged in a fire-fight rather than hand to hand combat.

The expenditure of some 29 000 rounds of ammunition by the garrison can possibly be explained in two ways:

- The figures were fudged to make the fight look more intense than it was or

- That for most of the time the battle degenerated into a fire fight between foes separated by distance, in the dark, unable to see their sights nor their targets, and firing blindly in suppressing fire.

This is corroborated from excerpts from soldiers’ letters home published in The Red Soldier by Frank Emery. The Silver Wreath by Norman Holme plus Surgeon Reynold’s account, give us a different story.

Lt. Chard, for instance, tells us that the Zulus were “...taking advantage of the cover provided by the cook house ovens to keep up a heavy fire.”

On their initial assault: “...the main body of the enemy were close behind and had lined the ledge of rock and caves overlooking us about 400 yards to our South where they kept up a constant fire... the fire from the rocks behind us though badly directed, took us completely in reverse and was so heavy that we suffered very severely...”

Surgeon Reynolds noted that “...we found ourselves quickly surrounded by the enemy with their strong force holding the garden and shrubbery. From all sides, but especially the latter places, they poured on us a continuous fire...”

447 Pte. John Waters 1/24 stated that: “... they came about twenty yards, then opened fire on the hospital.” 1112 Cpl. J. Lyons 2/24 said that: “...they steadily advanced and kept up a tremendous fire”.

Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne DCM was convinced that the volume of Zulu firepower had resulted from captured weapons, and went so far as to say that the firing was: “...the cause of every one of our casualties, killed and wounded .. there was hardly a man even wounded by an assegai”.

29 000 rounds fired equates to approximately 200 rounds fired per man over the duration of the fight. Although this figure sounds inordinately high, looked at another way, one must divide this by 12 hours, and ammunition expenditure per man amounted to less than 20 rounds fired per hour – certainly quicker than at Kambula but hardly the rapid fire of legend with rifle barrels glowing red hot and defective cartridges breaking apart in the chamber. But I would go with the bruised shoulders, splitting headaches and ringing ears.

Building at Rorkes Drift after it had been burnt in the battle via Talana Museum

Postscript

In modern military ideology, a figure of 10% casualties or more of forces engaged is considered “catastrophic”. If one looks at both battles, both sides lost more than that number, so that neither side “won” in terms of this criterion. Both were equally disastrous for all parties concerned.

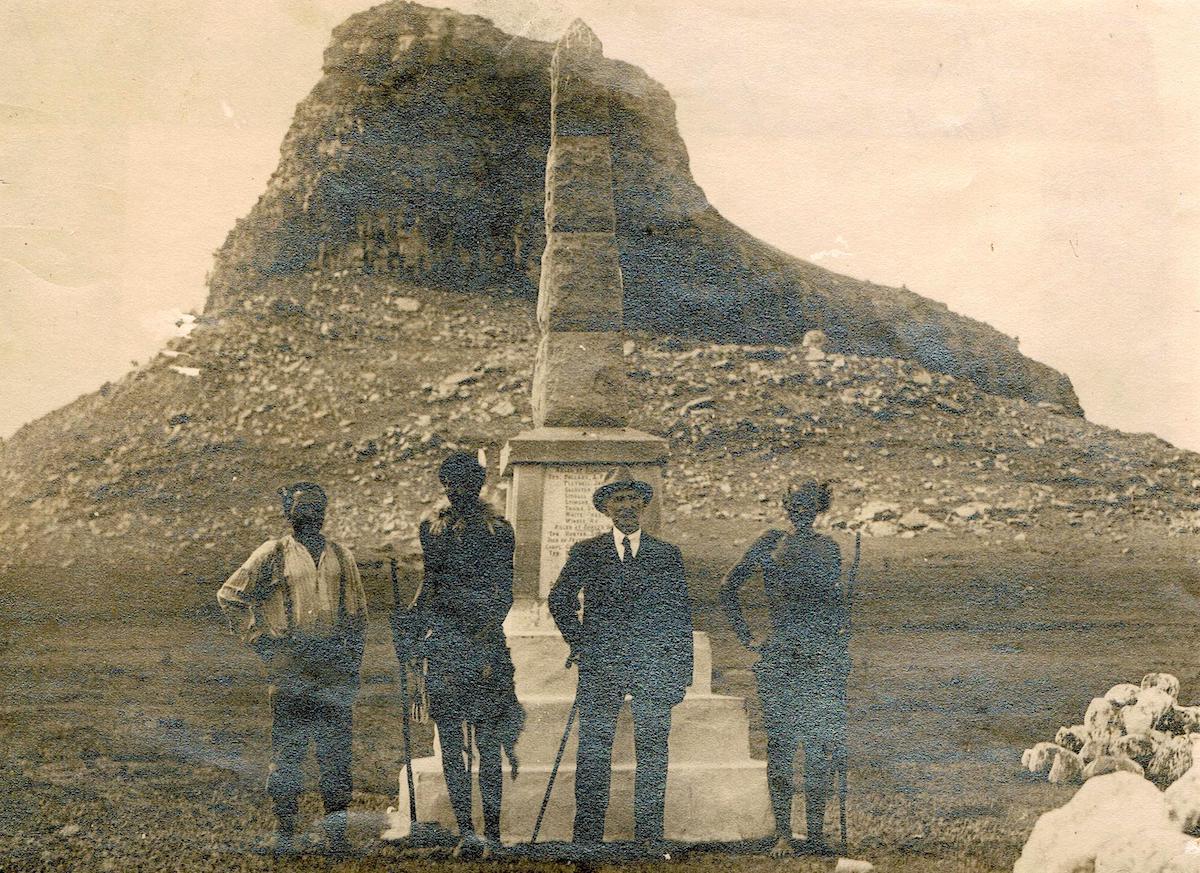

Main image: D Macphail with survivors from Isandlwana in 1929

About the author: Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

References

- Emery, Frank. “The Red Soldier”. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg. 1983.

- Grierson, Lieut. Col. James Moncrieff. “Scarlet into Khaki”. Lionel Leventhal, London. 1988.

- Hogg, Ian V. “Guns and How They Work”. Marshal and Cavendish. London 1979.

- Hogg, Ian V. “The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Firearms”. Hamlyn, Feltham, Kent. 1978.

- Holme, Norman. “The Silver Wreath”. Samson Books, London. 1979.

- Knight, Ian. “Go To Your God Like a Soldier”. Greenhill Books, London. 1996.

- Knight, Ian. “The Sun Turned Black”. Windrow and Greene, London. 1994.

- Rundgren, Pat. “What Really Happened at Rorke’s Drift?’ Lighthouse Publishing, Dundee, 2002.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.