Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The intriguingly sphinx-shaped mountain known as Isandlwana in Zululand lies in a flat valley carved out mainly by the Nxibongo River. To the north, the valley is fringed by the Nyoni heights and iThusi Mountain. Behind those is the next river valley, the Ngwebeni.

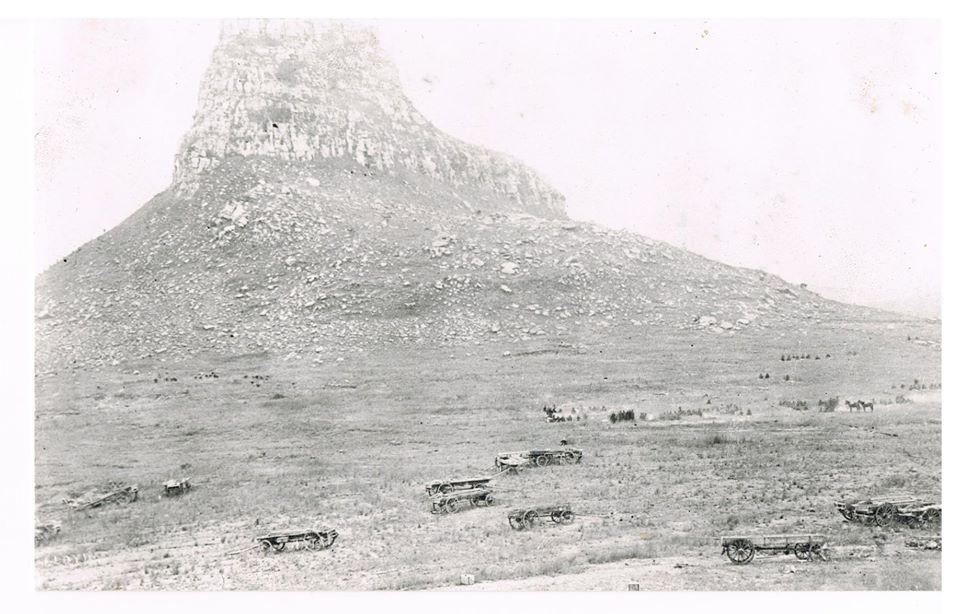

Isandlwana from Nyoni Ridge (Talana Museum)

When I first started off as a Battlefields Tour Guide, many, many years ago, one of the incontrovertible “facts” taught to me was that the Zulu army on its way to Isandlwana had cleverly avoided detection by British patrols and had managed to hide itself away in the Ngwebeni Valley, one river valley up from Isandlwana, on the day prior to the battle. When accidentally “spotted’ by Colonial scouts the following day, the massive army had uncoiled like a gigantic python and raced off to wipe out the British camp at the base of Isandlwana mountain.

Old photo of Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

Having regurgitated this story many times to my various tourists from the vantage point on the Mabaso Heights, overlooking the Ngwebeni Valley, I began to have my doubts about this aspect of the story. It’s obvious that the Zulu army used the valley at some time, as just around the bend in the river going eastwards, one can still find thousands of unfired Martini Henry cartridge cases lying discarded on the ground, primers intact but with the lead bullets removed. It is presumed that the Zulus rested here on their way home AFTER the battle, using the opportunity to take the bullets and gunpowder out from looted ammunition for use in their muzzle loaders.

When one drives from the Ngwebeni to Isandlwana, it is not just a hop, skip and a jump. The distance is some seven miles, which takes a while to drive, let alone run. Especially in view of the rough terrain, stones and heat. When tying that to the accepted timing and sequence of the battle, an anomaly arises.

It is common cause that Colonel Durnford left Rorke’s Drift just after 07:00 in order to proceed towards Isandlwana. The going was tough, especially for his rocket battery, and so Durnford could not have approached the camp earlier than 10:30 or so.

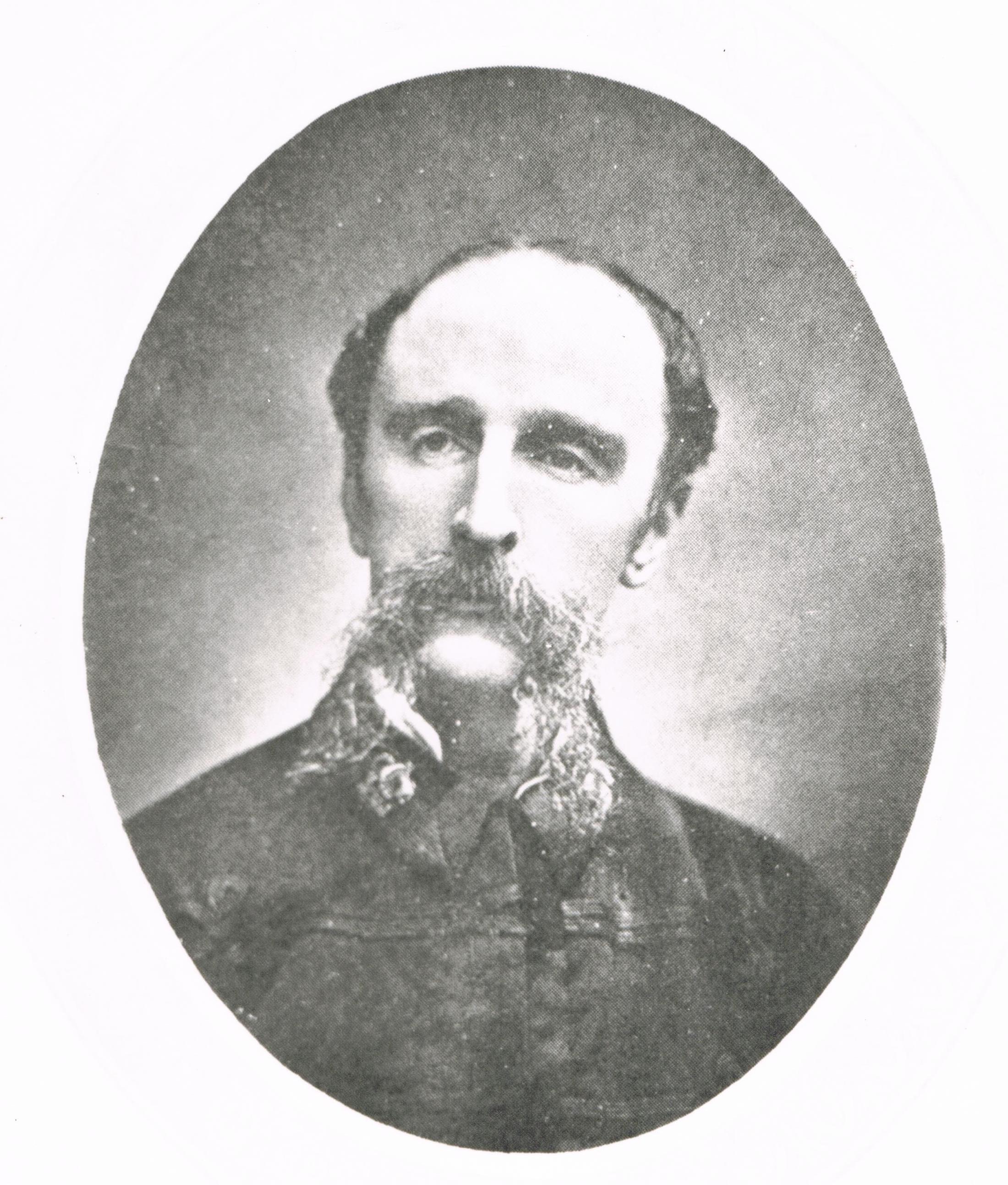

Anthony William Durnford (Talana Museum)

After a spot of breakfast and a SITREP from Colonel Pulleine, Durnford had decided to find out once and for all the position and strength of the Zulus fleetingly seen all morning on the Nyoni Heights to the north of the camp. He therefore dispatched three troops of horse under Shepstone, Raw, Barton and Vause to the Nyoni Heights and beyond towards the Ngwebeni. This could not have been much before 11:15

Having dispatched his scouts, Durnford himself, characteristically fretting from his forced inactivity, waited for the arrival of his Rocket Battery. Because they were relatively mobile, he had decided to place them on the notch next to IThusi Mountain to cover Raw’s advance along the plateau.

665 Private H. Grant 1/24th on detached duty with the Battery and an ultimate survivor of the battle, stated that they had arrived at Isandlwana at about 11 a.m. and remained in camp for about 15 minutes. 196 Private J. Trainer 1/24th, also on detached duty, thought it was a little earlier, around 10:30.

Durnford had given them a few minutes to bolt some lunch, and then led Captain A.F. Henderson’s troop of mounted Basothos and Captain H.D. Davies’ Edendale Troop of Natal Native Horse out eastwards towards the conical hill and beyond.

Major Russell, together with Captain Cracroft Nourse’s escort of 100 or so NNC took a more northerly course behind Durnford along the foothills of the Nyoni Heights before beginning to climb up towards his appointed position on the notch.

The conclusion to be reached, then, is that Durnford’s mounted troops could not have left the camp for the Nyoni Heights much before 11:15 and it would have taken them at least 20 minutes to get up to iThusi and surrounds – say 11:35.

The ride to the Ngwebeni Valley from there would have taken them another 20 minutes – up to, say, 11:55. After firing a volley, which would only have served to annoy the Zulus, they retired post haste with the Zulus in hot pursuit. Some 15 minutes later, at about 12:10, the battle commenced.

This is where the timing starts to go awry. A seven mile run, followed by a deployment of 20 000 men in the traditional Zulu “bull’s horn” pincer formation over a five mile front to all arrive at Isandlwana at approximately the same time - all this in less than half an hour? Clearly, it is absolutely impossible, even for super-human Zulus.

A re-enactment of the battle (Talana Museum)

Others arrived at the same conclusion. This apparent anomaly in the timing of the battle has been extensively researched by Ron Lock and Peter Quantrell. In order to prove their point, they organized members of the Isandlwana Marathon Club to run the alleged route taken by the Zulus from Ngwebeni to Isandlwana. It took professional athletes a minimum of 93 minutes to do it. Which is four times longer than the Zulu army is alleged to have made it. They would have required at least another couple of hours to do so and deploy – the so-called “missing hours”.

We know that the “right horn” had deployed by sunrise and was already in the region of Magaga Knoll (also known as Mkwene) by 05:00. At that time Pulleine had dispatched Cavaye’s “E” Company and Barry’s NNC Company towards the knoll in response to a sighting of Zulus in that vicinity and put the remainder of his force on standby.

This is corroborated by Chard, who recounted how he had borrowed a pair of binoculars to observe Zulus seemingly “in great force” on the Nyoni Heights. This could not have been much after 08:00.

The “left horn” had also deployed and by early morning was to be found in the dead ground between Qwabe and inKanyezi. According to Trooper W.W. Barker of the Natal Carbineers, the Vedettes had left the camp early that morning and were posted “to the direct front and left (i.e. east and north) of the camp, from three to five miles away. Hawkins, my bosom friend, and myself were posted on a hill to the extreme front (Qwabe), quite six miles from camp. After being posted for about a quarter of an hour we noticed a lot of mounted men in the distance… but had to retire off the hill post haste, as we discovered they were Zulus. We retired to Lt. Scott, about two miles nearer camp (Conical Hill) and informed him of what we had seen. Trooper Whitelaw reported a large army advancing (from the left or northern flank). Shortly afterwards, numbers of Zulus being seen on the hills to the left and front, Trooper Swift and another were sent back to report”.

So, then, both “horns” of the Zulu army had already started to deploy by sunrise or shortly afterwards.

Lieutenant Charles Raw’s account of the discovery of the main Zulu army has been misinterpreted for a century. He puts the position of the main body of the Zulu army in the western reaches and not in the main valley of the Ngwebeni.

In his own words, “We left Camp proceeding over the hills, Captain George Shepstone going with us. The enemy, in small groups, retiring before us for some time, drawing us four or five miles from camp, when they turned and fell upon us, the whole army showing itself from behind a hill in front where they had evidently been waiting”. There are no “hills” in that area, but other accounts refer to a “:ridge”, and there are plenty of these. It is concluded that the “hill” referred to was NOT the Mabaso, overlooking the Ngwebeni Valley, but was a “ridge” that was much closer to the camp.

The conclusion to be reached is that, in order to deploy their main force to attack just after midday the Zulus MUST have been considerably closer, such as just over the Nyoni Ridge, already loosely deployed and on their way, when “discovered”. The Zulus might well have been near the Mabaso Heights earlier on that morning but by the time they were discovered later on in the day they had to have been a damn sight closer.

Zulu Memorial at Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

This leads to a secondary conclusion – that there was a massive failure on the part of the British and Colonial scouts to appreciate the significance of what was happening around them. If we accept that the Zulus would have been approaching Isandlwana much earlier than originally reported, then the British scouts on the various look-out points MUST have seen them. Having done so, they either misunderstood the significance of what they were looking at, or else reported their findings to higher authority but there would have been at least a half hour time lapse before they were able to get back to the camp with their intelligence. Did they ever report? Were they believed? Was more time wasted while their reports were being verified?

Or else, faced with such an appalling prospect, did they simply take to their heels and prudently disappear early?

The author talking medals (Talana Museum)

If you would like to visit the battlefield and hear the stories first hand contact the author - gunners@trustnet.co.za

Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Main image: 24th Memorial at Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.