Jacqueline Kalley is proud of her descent from Dick King, the Natal pioneer who stands tall as a folklore hero of the early 19th century when Durban was very young. He is South Africa’ Paul Revere because he made his epic ride in 1842 from Port Natal/Durban to Grahamstown to summons help when the early English settlers and troops were under siege by Andries Pretorius, the Boer leader, and his Voortrekker clan who sought to extend their own Republic of Natalia. King was young and adventurous, he was an elephant hunter and a trader. He came of 1820 settler stock. He was a frontiersman and an excellent rider who could and did turn his hand to anything.

Dick King (Wikipedia)

His fame rested on that record breaking 10 day journey. Covering a distance of 600 miles or 960 kms, it was a test of courage and endurance. Throughout his life King regarded swimming as an essential acquired skill for his children and certainly his own experience on that epic journey showed why swimming meant survival. He had to ford between 180 and 200 coastal rivers and he swam many. King reached his destination, British troops did arrive by sea and the Boers were defeated. The outcome was that Natal was annexed by Great Britain in 1843 and two years later the first Lieutenant Governor, Martin West was appointed. The acquisition of another British colony in Southern Africa in the 1840s opened the way for British administration, land surveying, land sales and the arrival of several thousand Byrne settlers who made their homes on farms and in the towns. Natal and its natural harbour but with the barrier of the dangerous sand bar was considered to be strategically important. In those days it was an Eden with its lush tropical bush, a beautiful bay and port and grand vistas. By that stage it was game, set and match to the British and the losers were the Boers who trekked back inland over the Drakensberg to the Transvaal.

King never wrote his memoirs and his biography relies on oral history. He lived at his farm Isipingo of some 6000 acres, outside of Durban, and built the house that became known as the Dick King House. He married Clara Noon in 1852 and fathered seven children. King became a substantial landowner, including owning the land on which the Trappist Monastery at Marianhill was later founded. In the 1850s he was a pioneer of the sugar industry. Two brothers-in-law established a sugar mill at Isipingo. Kalley usefully covers Isipingo history in the book. In 1867, following the discovery of diamonds, King had made the decision to move to Kimberley to embark on prospecting but ill health was an obstacle. He died in 1871 and was buried in the Isipingo Cemetery. His widow Clara later remarried and died in England in 1908.

The highlights of the King story have been told many times. All of the early histories of Natal (Bird, Hattersley, McKeurtan) told the story of how he “saved Natal”. Perhaps the fullest previously published account of King’s heroism was the Cyril Eyre long pamphlet “Dick King, Saviour of Natal” published in 1932. Jacqueline Kalley as the great granddaughter of King through maternal descent tells the history of King but this time from a more family oriented perspective. She has also provided a simplified family tree to show how she and her sister are the descendants of Dick and Clara King.

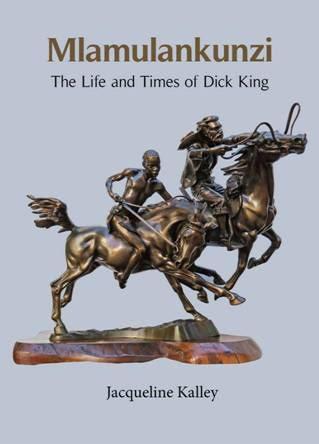

Certainly by the 21st century there is space for a reinterpretation. Kalley accepts the oral account of the then young black man who accompanied King on his ride for much of his way. She gives Ndongeni Ka Xoki, described as the groom, a voorlooper and a faithful employee of King, a leading part. It was Ndongeni who calls Richard King by his honorific and affectionate Zulu name of Mlamulankunzi – meaning “a peacemaker among bulls”. Such a name was a mark of respect and admiration. Hence the title of the book and clearly the intention to write the King biography with an African slant.

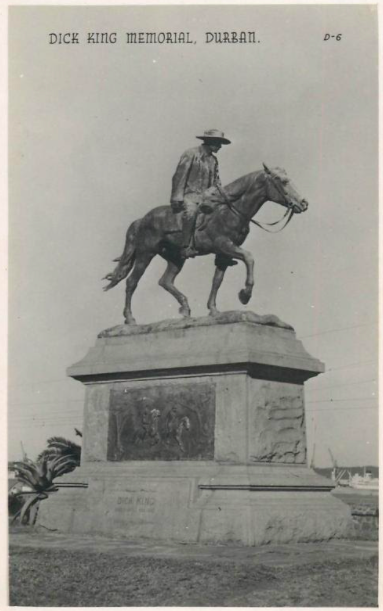

An early black and white post card of the Dick King equestrian statue

Jacqueline Kalley has been interested in King for many decades and wrote an early article for the history journal Natalia in 1986 (volume 16 – available on line from the Natal Society Foundation). She has tried to bring in as much new family material as possible but the sources seem limited. We are introduced to a John Anderson who was married to a Mary King, but who does not appear to have been related to Dick King. The Anderson side of the family remains sketchy, but a Alfred Anderson married the granddaughter of Dick King. She was Audrey King and the grandmother of Jacqueline Kalley.

The King history is the core of the book. Curiously Kalley fails to cite the biographical entry on King in the Dictionary of South African Biography (volume 2 , 1972, a long entry page 363-365 by Dr BJT Leverton who was chief of Natal Government archives in Pietermaritzburg).

Leverton had King’s date of birth as 1813 and Kalley also follows that date saying that at the time of the Kennersley Castle voyage to South Africa in 1820, King was 6 years old (though in her 1986 article she says he was 8 years old). The 1820 genealogical records provide the information that Richard Philip King was born on 26 Nov 1811 at Cam, near Dursley, Gloucestershire, England. It is a small detail but a new bit of information that is very easily tracked.

Kalley’s Prologue puts the spotlight from the very start on the account of Ndongeni and his association with King and the impression given is that Ndogeni was present at the unveiling of the 1915 Durban equestrian statue. However, there is no archival reference for this account by King’s companion and the most important eyewitness to and participant in the gallant ride. Instead the end note for the Prologue makes reference to the statement made by Ndogeni in 1897 to Magistrate Beachcroft and it was an account published in the records of the Legislative Assembly of the Colony of Natal also in that year. In 1905 there were further Ndongeni statements made to James Stuart and a Mr J J Jackson. All these accounts were published in the Cyril Eyre book. These accounts are worth a close reading because the broad outline of events remains the same but there were some discrepancies. King’s wife, Clara Noon King and also her second husband, a Mr J H Russel, were dismissive of the role of Ndongeni in their recollections. In their memory, King was the sole hero. How does one allow for these differences? Kalley places great stress on the recollections of Ethel Campbell who interviewed Ndongeni in 1911 some 69 years after the key event. The details about Ndongeni though remain fairly sketchy though he lived to be an old man.

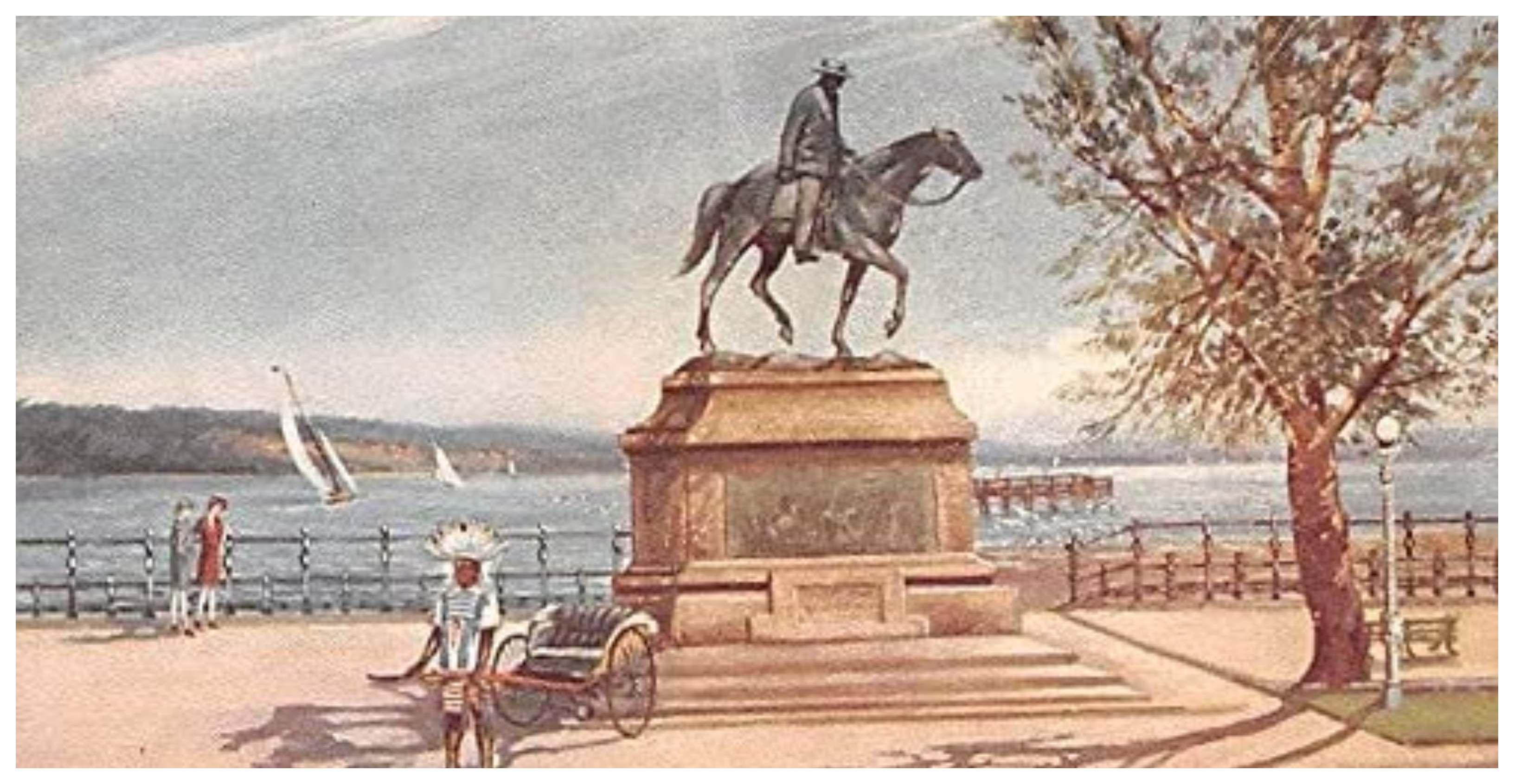

The popular view of Dick King over the decades has been moulded by the Durban public memorial. It is an equestrian statue on the Esplanade (now Margaret Mcadi Avenue). It has always been a popular Durban tourist landmark. It tells the story of Dick King and also shapes that story. The statue was commissioned in 1905 and unveiled in 1915. It was funded by public subscription. A memorial committee was in charge of making it happen; the idea had first been mooted in 1862 then dropped only to resurface in 1905. But raising the necessary £1500 was a tough challenge, and the fact that it was a statue erected some 73 years after the event means that it represents a much later view of what happened and puts a much later gloss on the the significance of the event. The artist was a Canadian sculptor, Henry Harley Grellier (1880 – 1943) who immigrated to South Africa. This work is the best known of Grellier’s work. The bronze statue was cast by Ascoli Brothers of the Carrara Marble Company in Italy who also had a Durban enterprise. The bronze side panels were cast locally by Ascoli. It seems that Ascoli Brothers also claimed authorship but this was not a valid claim although they may have been responsible for certain modifications to the design as requested by the managing committee. One is reminded of that old jibe that the camel is a horse designed by a committee. So perhaps it was fortunate that Durban acquired a horse and a rider as its statue! The equestrian statue shows an exhausted horse and his worn out rider, King and his horse, Somerset, at the end of his journey. The man and his horse are positioned on a substantial plinth and around the base are two bronze panels telling more of the story of the start of the journey and the urgent race against time to save the settlers and troops at the Fort. The plinth was designed by the Durban architect and artist Wallace Paton and another error has been to attribute the statue to Paton.

There are certain important clues in this statue and its panel and Kalley has included the statue and photographs of its side panels in her book. However, she misses the controversy at the time of the creation of the statue. The first panel shows King and Ndongeni being rowed across the bay by Joseph and George Cato with the horses towed behind the boats and the second panel shows Undongeni (Sic) and Dick King setting off on their ride but there is no description or analysis of what the panels represent or why these graphic moments were chosen by the artist. The panels have become the factual record of what happened.

The main Dick King statue presents the sole figure of King as the heroic if exhausted rider. There is no Ndongeni on his horse. There is a missing second figure and a missing horse. In 2015 this statue was defaced with paint by angry protestors wanting to destroy or make a statement about apartheid and colonial artefacts. The Natal Witness on 15th April 2015 published a photograph showing what had happened to the statue. It was all part of the visible and easy to attack art remnants of the old order. It pointed to the need for reassessment. This controversy is mentioned but it could have been an important part of a modern take on the King story.

The statue covered in paint (Natal Witness)

Perhaps Kalley did appreciate the difficulty because she did not use a photo of the well known King memorial for the cover of her book but chose a lesser known more modern bronze sculpture by Llewelyn Owen Davies created in 1983. The artist said he created the work because the 1915 man on the horse Esplanade bronze disappointed him and only shows one rider. There is no discussion of this work in Kalley’s book or why it is a reinterpretation that she clearly favoured. I simply found out that the small bronze sculpture was sold at Cannons Auctioneers in Hilton for R36 000.

Book Cover

I recommend an important article by Sabine Marschall: “Negotiating public memory: the Dick King Memorial in Durban" (Southern African Humanities, vol 17, Dec 2005) which actually predated the 2015 debacle to learn a bit more about how history is made not by an event but by a representation in a work of art and how a commissioning committee becomes the hand behind the history. The creative ideas of the artist are also there but in this particular case the artist was not given a free hand. There is a twist in the story because Marschall’s research revealed that Grellier intended to depict Ndongeni, as part of the main sculptural group on top of the pedestal but his proposal was blocked by the memorial committee. It could have been a unique work and instead the work of art both shaped and reflected the popular interpretation of the time. The story of Dick King then became the story told by a memorial.

Dick King was also remembered in a series of 10 granite road markers/pylons placed along the route. These were erected in the 1940s tracking the journey of Dick King and Ndongeni. They were sited at Isipingo Beach, Port Shepstone, Umzimvubu River, Port St Johns, Old Bunting Mission, Mancam Peddie and Trompetter’s Drift. I do not know whether these pylons are still extant perhaps Heritage Portal readers can contribute more to this account. [Editor's note - William Martinson has captured entries for all ten of the granites markers on Artefacts. All still exist - one relocated.]

Port Shepstone Memorial Marker (Boer and Brit)

Isipingo Marker (Nirun Dowlath)

This is the memorial tablet in the clock tower at the Grahamstown Town Hall (Artefacts)

A new book on Dick King at the end of the second decade of the 20th century surely should not have ignored the artistic debate. It is important because the story of Dick King extends beyond the family archives and a family history but is also about how history is written and rewritten most especially when a new generation of young people asks new questions about the past and expects revision and new answers. The Kalley book and her own research shows that she has something new to say about Dick King and his companion but the family history is the strongest motivation in the narrative. There is the hint of a black history revision but the author does not take that line of thinking far enough.

Kalley’s book is an earnest endeavor to write family history and extend the Dick King Heroic story to include his Zulu retainer. It will appeal to a new generation of KwaZulu-Natal enthusiasts and Africana collectors keen to review some Natal history. It is interesting and entertaining. It includes many black and white photographs but too many of the principal photographs are without labels or are not integrated into the text. With a price tag of over R400 from Clarke’s bookshop in Cape Town or R320 from the publisher at the time of writing, it is an expensive book. A limited print run means though that the book is likely to become a collectors‘ item.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.