Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The first few Indians in South Africa were imported by the Dutch East India Company in the seventeenth century as slaves. They were mainly from Bengal and South India. Simon van der Stel’s maternal grandmother, Monica da Costa (Monica of the Coast), was from Bengal. Some Indians were also aboard ships that were wrecked off the Cape Coast. A few of them survived and became spouses of the local inhabitants. In 1820 a number of Indians from Bencoolen were brought to the Cape by Mr Hare on the condition that the colony was not to be responsible for these Indians. Some planters also brought in Indians at their own expense.

The majority, however were brought here by the British Government as indentured labourers to work on the sugar cane plantations. Most of them were from Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The other group of Indians were referred to as “Passenger Indians” as they came at their own expense. The first group arrived in 1869. They were mainly entrepreneurs from Gujarat, many were traders, artisans, teachers and shop assistants.

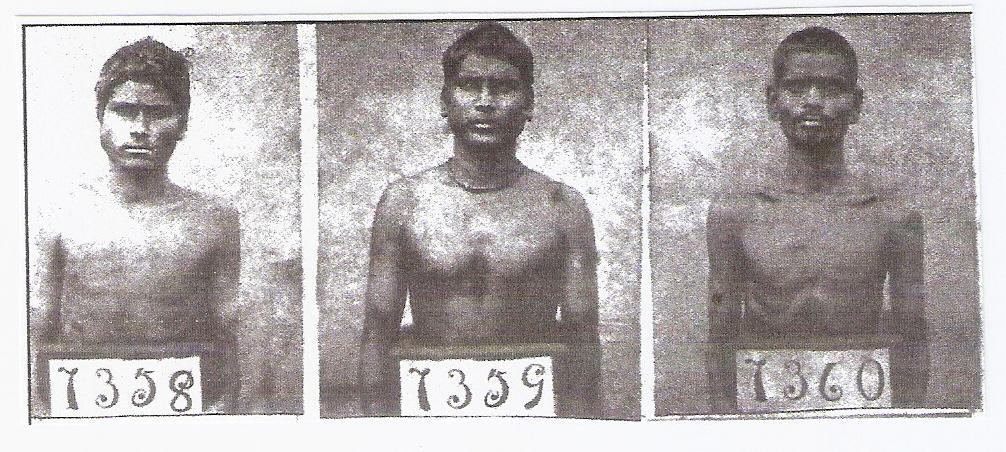

Labourers working on the sugar cane fields

In 1843 Natal became a British colony. The province was poor and undeveloped, so every effort was made to attract European settlers. New agricultural ventures were implemented.

On 30 January 1852, after numerous trials, Edmund Morewood succeeded in perfecting the production of sugar cane on his farm, Compensation. This success story brought more colonists into the country.

Theophilus Shepstone, Natal’s Secretary for Native Affairs from 1845 to 1846, had moved large numbers of blacks to the six reserves marked out in various parts of Natal and in so doing he had deprived farmers of readily available, cheap labour supplies.

The Zulus, the indigenous people, refused to work for the Whites. It was not that that they were lazy, the Zulu men were warriors and it was the women who worked on the fields. James Saunders who had worked with Indians in Mauritius was one of the planters who recommended to the government that Indians be brought here to work on the fields. A petition for Indian labour was then sent to the authorities by the White planters.

From 1866 many parts of India were struck by severe famines and epidemics. In 1875 there was a cholera epidemic which resulted in severe loss of life. Life was a continuous struggle for the people of India. When the arkatis, the recruiters called at the villages, the people grabbed this opportunity to go to South Africa. New recruits were promised land, wealth and better prospects in Natal. Thousands of people left their villages in droves to seek a better future in Natal.

Once the people had signed the agreement for recruitment, they left their villages with their meagre belongings tied in a bundle and placed on their heads. Agreement became GIRMIT for our forefathers. They then trudged along to Madras or Calcutta, the ports of departures. For many, the ports were miles and miles away from their villages. Many people lost their lives along the way because of weariness, hunger or illness. When the Indians eventually reached the ports there was a further delay as enough recruits had to assemble before the ship could set sail. Also, Emigration Agents had to procure a fixed percentage of women with each batch of emigrants.

Many of the arkatis did not give the Indians correct information about Natal, neither were they given maps or guides and in many instances no mention was made of the sea! If a person wanted to cancel the agreement, the arkatis demanded payment for expenses incurred. There was no choice but to continue.

Each passenger was given a pass and a “tin-ticket”, an identification disc hung around the neck or strapped to the arm.

Early Indian immigrants to Natal with tin tickets

On 4 October 1860 the barque, the Belvedere set sail from Calcutta with 342 passengers. On 11 October 1860 the boat, the Truro left Madras with 342 passengers and anchored in Port Natal on 16 November 1860. The Belvedere only docked in Port Natal on 26 November because the journey from Calcutta took longer.

An extract from an article written by a reporter from the Natal Mercury; “Thursday, November 1860- On Friday afternoon last, the 16th inst, the large barque Truro made the anchorage, and signalled the fact of her having a large number of Coolies on board. Considerable apprehension was at once experienced as to the sanitary condition of the vessel. …………………………………..The boats seemed to disgorge an endless stream of living cargo, Pariahs, Christians…………………………………………”

Before the Indian immigrants arrived in Natal the Natal Immigration Law of 1859 was passed. This was a long list of rules and regulations that the recruiters, ships’ captains and ships’ doctors had to follow. But sadly these rules and regulations were not followed by most of the authorities concerned.

In the early days, life for the recruits on the ships was horrendous. For many this was the first sight of the sea, the Kala Pani, the Paglaa Sumundar (black Waters). There are many records of the Indians being abused and humiliated by the ship’s captain, ship doctor or the crew. Women, especially the single women travelled in fear for they were quite often taken advantage of. In 1886, passengers on board the UMVOTI XVII complained about the ship’s doctor, Dr Paterson, about assault and improper relations with the females on board. The doctor was charged for improper conduct but he got off lightly. Sometimes the journey was also fraught by illness, disease or death.

Upon arrival in Port Natal, there was more trauma for the Indians as they were gawked at by the Whites and Zulus because of their strange tongues, their dress and their complexions. The Indians were referred to as Coolies. In Tamil the word KULI means payment for menial work done.

The Indians disembarked at the Point which was the depot. They then proceeded to the quarantine station at the Bluff where they were processed before being dispatched to their respective employers. People who were ill or handicapped were sent back to India.

A ships’ list was drawn up by the British clerks. This is THE MOST IMPORTANT document that has the information that gives you the details of the Indentured Indians. We are grateful to the British for this for it assists us in tracing our roots. Many names were misspelt because the clerks did not understand the Indians. To make lives easier for themselves many of the British then referred to the Indians as Mary and Samy!

The presence of the Indians was greeted with animosity and hostility. Every step of the way, their situation grew worse. The Indians were then provided with meagre rations and dispatched to their work places which were far and wide. Many died on the way. When the Indians arrived they found that proper housing was not provided for them, they had to erect shacks made from leaves and branches. These temporary abodes did not protect them from the weather, Illness struck. Medical assistance was lacking. It took many years before the employers provided decent accommodation in the form of barracks.

The Indians were sent to work on the sugar cane fields, railways or to work as special servants, ayahs (Nannies) for the White children, waiters or cooks. The Indians lived in atrocious conditions , their wages were low and sometimes they were not paid. They had become slaves to the White man.

The White man also caused animosity amongst the Indians. Indian men who could speak in English were employed as sirdars (overseers). Many of these sidars abused their powers and mistreated their fellowmen.

There were many Indians who wished to return to India but they could not, for they had to honour their agreement of five years of work, Further, many had no money to go back or they had alienated themselves from their families. By this I mean that they had lived and eaten with other caste groups. In India, then, caste defined a person.

The Indians had to make many adaptations with regards to religion, language, caste, dress and food in order to survive in this land. Part of the ration of the Indians was mealie meal. The staple starch of the Indian was rice. There was no rice. So you eat what you get to sate your hunger pangs.

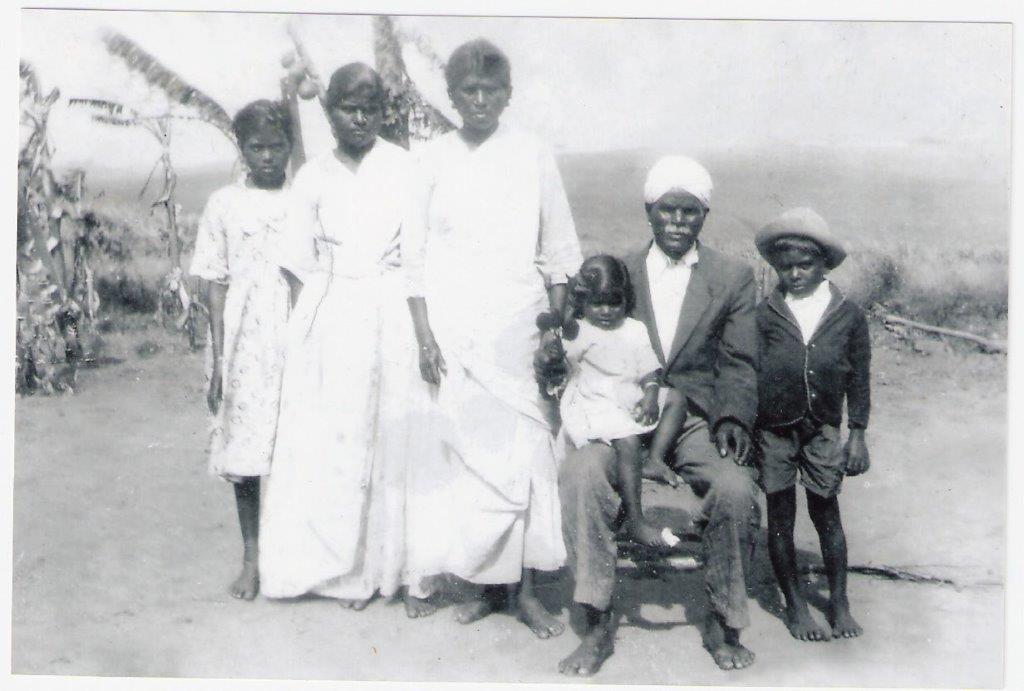

One of the many temples built by Indentured Indians

But this did not deter the Indians for they were very enterprising. After their daily slog in the fields they tilled the land around their homes. Here they planted seeds from India. The crops that they harvested provided them with enough food. The excess they sold to the locals and their employers. This will to survive, to prosper, to make do with what you have infuriated the Whites.

“….by means of his rabbit–like fertility, the Indian has literally ousted the White man not only from his occupation ,but literally from standing room…”

Once the worker had completed his period of indenture he could return home or continue to find employment here. As many could not afford to go back home they chose to remain in Natal. There were also others who remained for they found that they could prosper here. Some re-indentured and some leased or bought small plots of land which they cultivated.

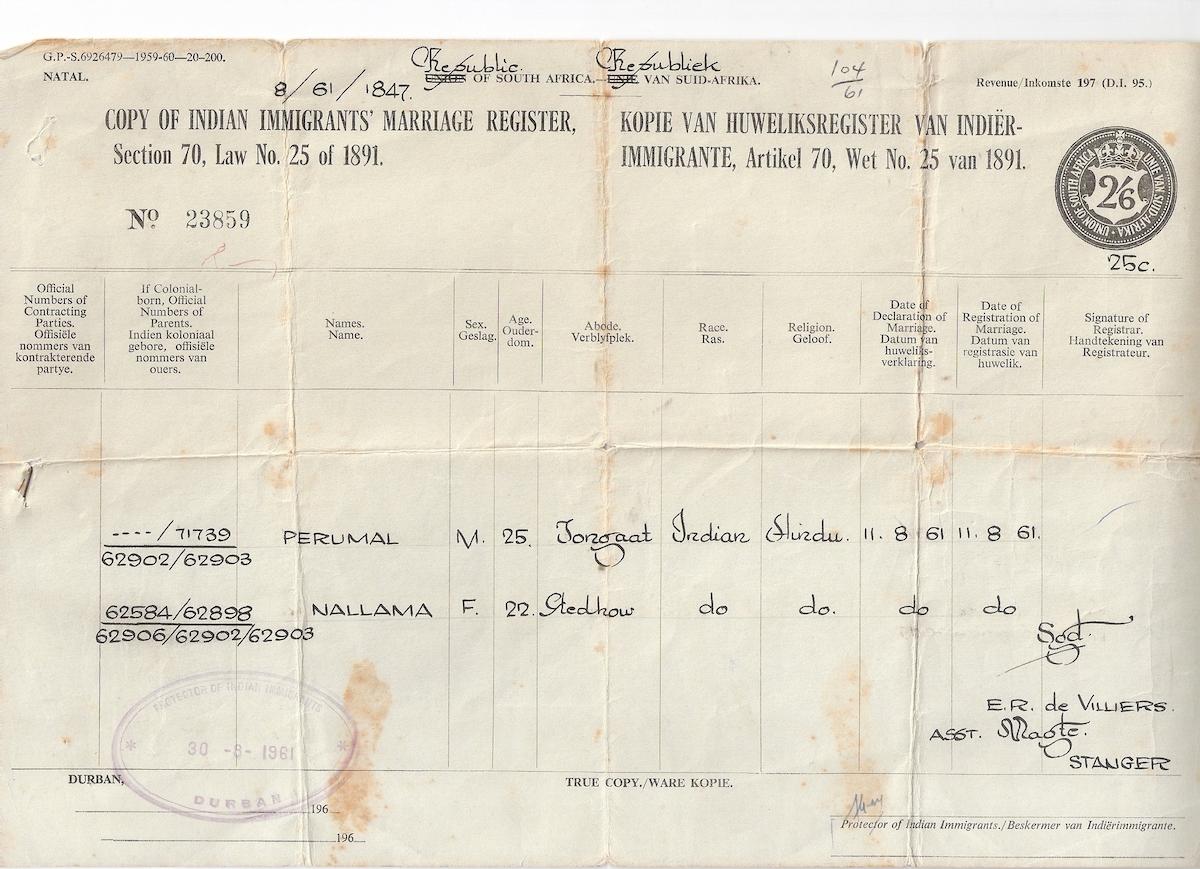

Old Marriage Certificate

From 1866 to 1874 immigration was discontinued as a result of world wide recession. Trade revived in 1871.

On 13 February 1871 the first group of repatriated ex indentured Indians returned to India on the Red Riding Hood. It was then that some of these Indians lodged complaints at the protector’s office about unfair conditions of employment and ill treatment by employers.

An official Board of Enquiry was set up to investigate these claims. This Board published the document The Colie Commission on 11 September 1872. The commission listed the grievances of the Indian immigrants. Thereafter a new set of regulations was published: Indian Laws and Regulations. This went on until finally the Wragg Commission of 1885-1887 was published. The Indian Immigration Act, Act XXI of 1883 was then enforced on 1 April 1886. However, all these acts still did not make the lives of the Indians easier? There was still prejudice and animosity against the Indians.

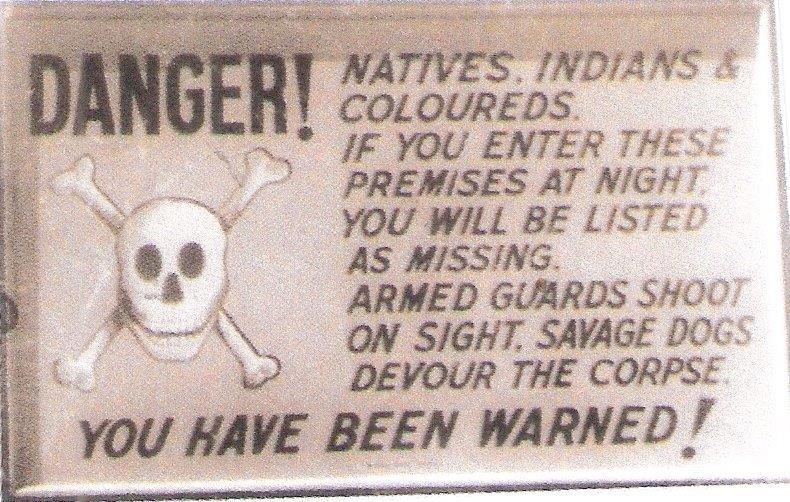

Prejudice was rife

Just one account of abuse against the Indian; The White employer was very angry with Ramasamy. He tied Ramsamy up on a nail on the wall and whipped him with a sjambok. He hit Ramsamy very badly but Ramsamy could still wiggle about. This enraged the boss. He tied the poor man to the rafters of the roof and he hit and hit until he could hit no more. Ramsamy’s back was finished. The skin fell off and blood poured. Ramsamy was taken to the magistrate, the magistrate listened and then ordered him back to the estate because they did not have passes. Ramasamy did not go back to the estate. They walked back to Durban and complained to the Protector. But, the protector arrested them for desertion and threw them into jail!

Immigration continued until 21 July 1911 when the last shipment of indentured Indians arrived in Durban on the Umlazi XVIII. A total of 384 ships transported passengers and over 152 184 Indians had arrived in Natal. Some of the reasons for Indenture being concluded were: Natal’s determination to allow no fresh Indentured Indians to remain in the colony which is coupled with the infamous Three Pound Tax “penalty upon residence” and the repressive laws of 1897 with regards to immigration and renewal of trading licences to “free passenger” Indians.

The Indians were enterprising people , just the same as all pioneering people around the world. They scrimped and saved and ensured that their children were educated so that they could get jobs and become prosperous. There were no schools or religious institutions. So they built their own by collecting funds from the community and their employers.

Over the years the Indians have made huge contributions in all fields towards the building of this country. Granted, there were some who were weak, some were lazy and some were rascals and louts but the majority were hard working people.

Headstone on grave of Indentured Indian

The following statement from C.G. Henning’s book “The Indentured Indian in Natal 1860-1917” summarizes the adversity and triumph of the Indian “They will never be able to eradicate the knowledge of the extreme pain which the immigrant Coolies suffered and deny the heavy price they paid with their life’s blood so that their descendants might live in comfort and decency.”

About the author: Tholsi Mudly is a retired educator who is passionate about heritage preservation. She is the author of two books: A Tribute to our Forefathers and Living the Legacy. She is also the Chairperson of the oThongathi Museum Committee.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.