Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

At five o clock in the afternoon of Saturday 19 December 1925, a wisp of smoke was seen to rise lazily from the thatched roof near the kitchen of the Groot Constantia Manor House. Moments later the huge thatch roof caught fire creating an uncontrollable inferno. With no brandsolder to contain the flames, the blaze crashed through to the boarded ceilings of the rooms below and through that to the main floor. Other than bare blackened walls and gables, nothing of the historic wooden roof beams, ceilings, heavy wood lintels, wooden doors, window frames and built-in cupboards survived this great fire. Furthermore, a great deal of the internal wall plastering damaged by the extreme heat peeled off and continued doing so because of subsequent exposure to the elements.

As architect Franklin Kendall FRIBA, entrusted by the Public Works Department in 1926 to restore this Manor House states in his book, The Restoration of Groot Constantia, ‘A more complete burn out could scarcely be imagined’. At the time, the destruction of this, the most historical farm house in South Africa, caused profound dismay, but in retrospect it may have been a blessing in disguise. The restoration of this Manor House, ably and sensitively overseen by Kendall, bar one possible criticism, offered opportunity to examine the layout of the original building and identify the extensive alterations and additions of the preceding centuries.

Fortunately, all the outbuildings escaped this fire and are therefore either part of the original estate, or date from the renovations carried out by Hendrik Cloete in the eighteenth century.

The public generally considers this historic Manor House, as seen today, to have been built by Simon van der Stel at the end of the seventeenth century. Unfortunately, this is totally incorrect and while the structure of the present building probably rests on the foundations of Van der Stel’s original house, there is little resemblance between the two buildings.

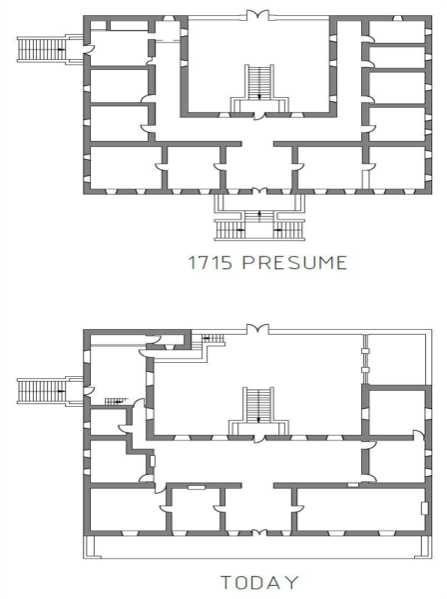

(Fig. 1) Presumed Ground Plan of Groot Constantia circa 1715, compared to present. The current Great Dining Hall did not exist in 1715, then merely an internal passage (Source Hans Fransen).

Unusually for the time, Kendall believed that to suitably restore a historical building all the written sources relating to it as well as its complete structure should be thoroughly researched and investigated. Fortunately, Kendall recorded all his findings and conclusions in the book referred to above, subsequently published by himself, which has become quite rare Africana. The Foreword in this book is by the late Senator F. S. Malan and Kendall dedicated it to Herbert Baker with the following inscription: ‘Who awakened an interest in the arts of the old Cape settlers and laid the foundation of a national architecture in South Africa’.

(Fig. 2) Franklin Kaye Kendall (Source Artefacts)

Kendall felt it would be impractical to restore the house to what it might have looked like during Van der Stel’s lifetime, as reliable information of its then appearance was lacking.

After some debate, Kendall accepted the brief to restore Groot Constantia to the principle of ‘Constantia at its best’. The outcome, what we see today, is probably even more impressive than in its heyday when Groot Constantia was owned for just over a century by the Cloete family. The restoration enabled Kendall to remove modern additions that detracted rather than adding to the house’s appearance, amongst others, a lean-to corrugated iron roof that had been added at some point to the back of it.

It was further agreed that the thatch roof should be retained at all costs as being essentially typical of the old Cape style. A brandsolder to the loft was required against a future possible fire and old building material was to be preserved wherever possible.

Granted the opportunity to thoroughly review the structure of Groot Constantia, Kendall concluded that at one stage almost the entire house had been rebuilt and considerably enlarged. As basis for his findings Kendall compared a 1741 drawing of this house by German draughtsman J. W. Heydt, to his own findings in the walls of the fire damaged building. He argued that Heydt’s drawing, which had previously not received much credence, showed the original house did not have any gables and probably accurately represented its original appearance when Van der Stel lived here.

(Fig. 3) 1741 Drawing of Groot Constantia by J. W. Heydt. The original house is to the middle-right and the smaller building in the middle is the staff dwelling, now the Visitor’s Centre.

When examining the surviving walls and gables, Kendall discovered that the height of the original house was much lower than what it appeared in 1926. Small Dutch klinker bricks used during the construction of the original building only reached up to the level of the current window sills and above this larger and more modern bricks were used. He found the central Gable above the window-sills to have been built with an indiscriminate mixture of the two kinds of brick, indicating it was a later addition. At the top end of the Drawing Room he also found two casement windows which had been filled in. Kendall concluded the sash windows in the front wall, about double the height of the now filled-in casement windows must have been inserted at the time that the original wall had been cut down to sill level to allow for the sashes to be incorporated at the main front and back walls.

(Fig. 4) Post fire photo showing blocked up original casement windows at end of Drawing Room (Photo by Arthur Elliot, courtesy of Iziko Museums).

Kendall discovered the high walls and gables were built using only soft bricks and clay mortar. Large buttresses providing support and rigidity to the gables and reaching almost to the same height only became visible after the fire. A continuous wall reaching some eight feet high above ceiling level and stretching across the building was also exposed by the destruction of the ceilings by the fire.

(Fig. 5) Post fire photo showing buttress supporting the Gable and elevated continuous wall above ceiling level (Photo by Arthur Elliott, courtesy of Iziko Museums).

The farm Constantia dates to 1685 when visiting VOC Commissioner Van Reede tot Drakenstein granted Van der Stel 800 hectares of land. It is speculated the farm may have been named after the daughter of VOC Official Ryckloff van Goens who originally proposed Van der Stel should be rewarded with a farm in appreciation of his sterling efforts to develop the Cape settlement. Van der Stel built his house on the Constantia Farm in about 1692. He retired to Constantia in 1699 where he lived until his death in 1712, aged seventy-three years. When Van der Stel’s estate was finalised in 1716, Constantia was divided into three portions, namely Bergvliet, Klein Constantia, also known as Hoop op Constantia and what later became known as Groot Constantia. Over time the Groot Constantia farm became increasingly run down until purchased in 1778 by Hendrik Cloete (1725-1799).

According to a subsequent record by his son Pieter Lourens, upon purchase the house and farm buildings were in poor state and the vineyards barely functioning. Hendrik Cloete went to great expense and effort to restore the buildings, plant vines and construct the iconic wine cellar situated to the rear of the Manor House.

From the second half of the eighteenth-century, Constantia wines became regarded as nectar fit for kings, dignitaries as well as deposed emperors such as Napoleon Bonaparte, banished to St. Helena Island.

(Fig. 6) The wines for which Groot Constantia Wine farm became famous from the middle of the eighteenth century onwards (source SJ de Klerk).

Four successive generations of the Cloete family lived and farmed at Groot Constantia from 1778 until 1885 when the farm finally went insolvent. Sadly, there was little public interest in buying a loss-making concern and this historical property was purchased by the Cape Colonial Government for a negligible amount, for use as an experimental wine farm. The Manor House became a residence for the students and the Farm Manager. It was still partially furnished with antiques from the Cloete era and while not quite a museum, it was accessible to the public upon request. Hence, it remained a popular tourist destination, which contributed to the wide-spread consternation when it burnt down.

(Fig. 7) Information Plaque at entrance to the Cloete Family Graveyard at Groot Constantia. Note the domes of the Cloete tombs beyond (Source SJ de Klerk).

Kendall probably surmised correctly that Hendrik Cloete first planted new vines, improved the extensive outbuildings and constructed the Wine Cellar prior to enhancing the Manor House, arguing, the Proprietor would probably finish his work with ‘something of a flourish by adding magnificence and comfort to the house itself’. We can therefore assume all the alterations to Groot Constantia between Heydt’s drawing and what we observe today, must be credited to Hendrik Cloete.

The long Dining Room is the most impressive room at Groot Constantia. In an inspired move Hendrik Cloete and his architect, widened the narrow passage running along the back of the original house, transforming it into an elegant reception area (see Fig. 1). Here, various dignitaries were entertained, such as the luncheon for Lady Anne Barnard and Lord Mornington, the dashing elder brother of the Duke of Wellington.

(Fig. 8) The elegant Long Dining Room (Source SJ de Klerk).

Although there is no supporting evidence, Kendall concluded Hendrik Cloete must have retained Louis Michel Thibault (1750-1815) to design the Wine Cellar, which in its finished state would have outshone the unaltered original farm house. Thibault arrived from France to the Cape in 1783, initially as military engineer and later emerged as the leading local architect. According to Hans Fransen, the middle section of the Wine Cellar crowned with the triangular pediment is typical of a Townhouse façade from that era.

The delightful stucco relief dated 1791, adorning the Wine Cellar pediment is attributed to Anton Anreith (1754-1822), who often collaborated with Thibault. It shows Ganymede, cupbearer of the Gods descending on Jove’s eagle, surrounded by frolicking cherubs. Apparently one of the cherubs underwent a gender change during a subsequent restoration!

(Fig. 9) 1791 Rococo-style stucco relief adorning the Cloete Wine Cellar pediment, attributed to Anton Anreith (Source SJ de Klerk).

About a dozen tenders were received for the reconstruction of the Manor House of which the lowest by Messrs. Hoheisen and Co., was signed off to the amount of £7493.

One of the urgent problems Kendall had to address was how to protect the unstable old walls denuded from most of their plaster from the imminent Winter rains. The soft bricks made from clay mortar would not have remained intact for long when exposed to rain and moisture. Fortunately, it was found that a solution of alum and soap sprayed onto the exposed walls served to adequately seal them against any moisture.

Kendal states that in the restoration of ruins in older countries the grouting of liquid cement has generally worked wonders. Unfortunately, in this case the walls were too soft and porous to withstand such treatment. Traditionally, many of the old Cape houses were built of local sun-dried bricks with the walls consisting of these bricks with a mortar clay and plastered over with lime. Groot Constantia was no exception to this manner of construction.

To repair the soft walls new bricks set in lime mortar of moderate quality were used to replace the original bricks which had collapsed, while wrought iron anchor ties were used to strengthen weak points in the building (modern cement does not adhere to sun dried bricks).

Reinforced concrete beams were laid on top of the old walls at ceiling level to brace both the walls and gables. According to Kendall these concrete beams anchored the walls below and provided the Gables above with firm points of contact for additional buttressing or support. The internal buttresses above ceiling level for the Gables shown in Fig. 5 were removed when the concrete beams were laid, and new buttresses of greater depth were constructed on the new concrete ceilings which provided a firm foundation.

This is the one aspect of the restoration which was criticised by the eminent architect, the late Norman Eaton, who subsequently oversaw the restoration of The Parsonage, also known as Reinet House, now the Graaff Reinet Museum. Eaton was not convinced that the erection of an obstructive reinforced concrete ceiling to replace the traditional brandsolder, even if strengthening and fire protection were given as the reasons, was appropriate for this historic building. He argued that both these objectives could have been achieved using traditional methods and without having to close off a large and interesting part of Groot Constantia to the interested visitor. Interestingly, Eaton makes the comment that Kendall was so sensitive about other things, that it is difficult not to suspect this was forced on him by some outside influence or authority. He goes on to say that nothing about it could now be done and visitors appear to have been deprived for all time of the enjoyment of this very important part of our most historic house.

(Fig. 10) The only controversial matter of the restoration - the concrete beams laid at ceiling level instead of the traditional brandsolder type (Source SJ de Klerk).

Traditionally, a brandsolder is constructed through coating layers of puddled clay or lime plaster on the beamed ceiling in which bricks or tiles are embedded. Not only did the clay or bricked brandsolder protect the lower part of the house against fire, a necessary protection during an era when all the roofs were thatch and no form of fire fighting consisted, but it also kept such houses cool in summer and warm in winter.

Kendall discovered the lower (East) Gable to be full of cracks and had ‘bellied’ out considerably. Initially, it was thought the whole Gable would have to be taken down and rebuilt but by careful removal of the crumbling bricks around the cracks and replacing them with good material reinforced with iron ties, the whole feature was preserved.

The front Gable, one of the chief attractions of Groot Constantia caused a great deal of anxiety. As Kendall states, ‘Consider the position. Here was a massive wall pierced by the wide central entrance and two flanking windows, with most of the weight of the Gable above carried on the teak lintels spanning these openings.’ Except that the fire had consumed the wooden lintels, hence there was very little support for the weight of the massive Gable.

A complete system of shoring was erected both internally and externally so that the front and other Gables would not collapse (see main photo). The gaping cavities where the lintels had been were carefully filled in with bricks in cement so that the Gable could rest on a firm base.

Some genuine old doors became available from one of the old houses in Cape Town which had recently been pulled down and were found to be eminently suitable for an old farm house such as Groot Constantia. The above comment made in passing by Kendall confirms how casually many fine old Cape buildings were demolished in more modern times. Incidentally, at the beginning of the 20th Century there existed more than 3 000 buildings and homesteads in the Old Cape style. Tragic to relate that at a census taken in 1966, fewer than 500 of these remained and of this number only 275 retained their original features.

Kendall was justifiably very proud of his efforts to restore Groot Constantia and his personal Ex Libris (Bookplate) displays the restored main facade of this beautiful Manor House.

(Fig. 11) Ex Libris of Franklin Kendall showing the front façade of Groot Constantia.

During the restoration process it was agreed that Groot Constantia would no longer be used as a residence and because of its historical significance would be refurbished as a museum. Obtaining suitable antique furniture was challenging as all its previous furniture had been destroyed by the fire. Fortunately for posterity, Alfred Aaron de Pass generously undertook to furnish the whole of Groot Constantia at his personal expense. De Pass and well-known antique dealer H. Robinson sourced suitable antiques from the Cloete era, which in turn were approved by Kendall and Major W. Jardine, Africana book and antique collector. Towards the middle of 1927 the furniture collection was housed for the first time in Groot Contantia. Other than a leading article in the Cape Times of 29 June 1927, which praised the generous donation of De Pass, his donation received little publicity. In the same year, without any formal occasion, the new museum was opened to the public.

(Fig. 12) Present appearance of the Groot Constantia Manor House (Source SJ de Klerk).

The government handed over the Groot Constantia Farm to an independent trust in 1993 and since then it has operated as a commercial concern, to which visitors have free access enabling them to enjoy this special part of South Africa’s heritage and purchase fine wines with a long history.

See brief biographies of Messrs. Franklin Kendal, Alfred de Pass and Major William Jardine detailed below.

This article is dedicated to Mrs. Bertha Sherman, wife of the late Rabbi David Sherman of the Cape Town Reformed Jewish Congregation, who officiated in 1952 at the memorial cremation service of Alfred de Pass, where he paid homage to him as one of Cape Town’s most generous art benefactors. Mrs. Sherman passed away in April 2019, aged 97, while this article was being researched and written.

Architect F. K. Kendall FRIBA (1870-1948)

Franklin Kaye Kendall was born in Melbourne Australia, but shortly after his birth the family returned to the UK. He studied architecture at the University College, London, becoming in 1894 an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects (ARIBA) and in 1912 a Fellow of this Institute. He briefly worked at the UK architectural firm of Ernest George and Yates before emigrating to South Africa in 1896. He joined the architectural firm of Herbert Baker and F. E. Masey as Senior Assistant and was appointed Junior Partner in 1897. When Masey departed the firm for Rhodesia, it became known as Baker and Kendall. Kendall played an important role in the establishment of the School of Architecture, initially part of the Michaelis School of Fine Arts, but later incorporated into the Faculty of Aesthetic Arts and Architecture at UCT. Some of the early works, both his name and that of the firm are linked to, include, the City Club, alterations to the Parliamentary Buildings, the Mount Nelson Hotel, and the Rhodes Memorial. Later works include, the National Art Gallery in Cape Town, the Crematorium in Maitland, the Kramat of Sheik Yusuf in Faure and the restoration of the Groot Constantia Manor House. Kendall and family lived in the graceful house ‘Pelyn’ in Kenilworth, that he designed himself, until shortly prior to his death.

Art Connoisseur and Philanthropist A. A. de Pass (1860-1952)

Alfred Aaron de Pass, art collector and connoisseur was born in Cape Town but completed his schooling in London and obtained a degree in industrial chemistry from the University of Göttingen. He worked for his father Daniel de Pass, a Cape business pioneer on the Reunion sugar estate in Natal where he researched new strains of sugar. Through family connections in Jamaica new strains of sugar cane were imported and tested and by 1883, a cane resistant to local diseases had been discovered. He retired from business at an early age to live in England and devoted himself full-time to the world of art. In 1926 he donated more than three hundred pictures and sculptures to the SA National Gallery. The Koopmans de Wet House also received works of art, but as a benefactor De Pass found greatest pleasure in providing Groot Constantia with suitable antique furniture. In recognition of his long and valuable service to the cultural life of South Africa, UCT conferred an honorary LL.D. on him in 1950.

Africana Book and Antique Collector W. Jardine (1867-1948)

Major William Jardine studied at the South African College (SACS) and Sydenham College, London. Upon his return to Cape Town he joined his father’s business in Adderley Street, and was appointed Partner in 1890. Always interested in voluntary military service, he joined the Cape Town Highlander Regiment and retired in 1904 with the rank of Major. From 1916 onwards, during the First World War, he served in East Africa and then Palestine as Captain of the Cape Corps. He was considered one of the most informed Africana collectors. In 1925 he retired from business and dedicated himself to collecting Africana books and artefacts. He built up his Africana library at his house Craigdhu, to such an extent that it became one of the most complete of the great private collections. The Library of Parliament purchased his library to complement the Mendelssohn Africana Book Collection. Jardine subsequently relocated to Applegarth in Sir Lowry’s Pass where he again built up a substantial Africana library and antique collection. He was one of the first to appreciate the historical and aesthetic value of Africana books and furniture in an era when there was little public interest in them.

The author wishes to thank:

- Ms. Lailah Hisham, Collections Manager of Social History Collections from Iziko Museums of SA, who provided electronic copies of the photos taken by Arthur Elliot of Groot Constantia, following the Great Fire and arranged unfettered access to the Groot Constantia Manor House; and

- Danie van Wyk who drew the Ground Plans of the house as it is presumed to have appeared during Van der Stel’s era and at present.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Bibliography

- Beyers C. J. (Editor). (1977). Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Deel III. Tafelberg Uitgewers Bpk., Kaapstad.

- Beyers C. J. (Editor). (1981). Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Deel IV. Butterworth, Durban.

- Beyers C. J. (Editor). (1987). Dictionary of South African Biography Volume V. Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria.

- Burrows E. H. The Age of the Manor-House of Groot Constantia. In Africana Notes and News, Vol 6. No 1. (December 1948).

- Dane P. & Wallace S-N. (1981). The Great Houses of Constantia. Don Nelson, Cape Town.

- De Bosdari C. (1954). Anton Anreith - Africa’s First Sculptor. A. A. Balkema, Cape Town.

- Fransen H. (Derde Uitgawe 1978). Groot Constantia - Sy geskiedenis en ʼn beskrywing van sy argitektuur en die versameling. Die SA Kultuurhistoriese Museum, Kaapstad.

- Fransen H. A. (2004). Guide to the Old Buildings of the Cape. A survey of extant architecture from before c1910 in the area of Cape Town – Calvinia – Colesberg – Uitenhage. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg & Cape Town.

- Groot Constantia. (1965-66). Issued by the Department of Public Works. The Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Immelman R. F. M. & Quinn G. D. (Editors). The Preservation & Restoration of Historic Buildings in South Africa. (1968). A. A. Balkema, Cape Town.

- Kendall F. K. The Restoration of Groot Constantia. (Not dated 1927?). Juta & Co. Ltd., Cape Town.

- Oberholzer A. M., Baraitser M. & Malherbe W. D. (1985) The Cape House and Its Interior – An Enquiry into the Sources of Cape Architecture & A Survey of Built-in Early Cape Domestic Woodwork. Stellenbosch Museum, Stellenbosch.

- Pearse G. E. (1933). Eighteenth Century Architecture in South Africa. B. T. Batsford Ltd., London.

- Schutte G. J. Editor. (2003). Hendrik Cloete, Groot Constantia and the VOC 1778-1799. Van Riebeeck Society Second Series No. 34, Cape Town.

- Van der Spuy K. (1969). Old Nectar and Roses. Books of Africa, Cape Town.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.