Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

For a greater part of the 19th century, abundant and large herds of game were common in the interior of South Africa, resulting in it becoming a “sportsman’s” paradise

Wild-life on the African continent clearly had a powerful hold on the colonial masters. Their imagination around hunting expeditions and stories were endless – multiple books were published on their adventures whilst on the continent. It was, as if, the fauna was there purely for their subjugation. Surveying earlier literature suggests that this often-senseless form of adventure was clearly widely acceptable and encouraged.

Colonial hunters were colourful figures. Combined with their colonial and aristocratic privileges one of the key factors that led to the spread of big-game hunting was the romantic European conception of hunting in Africa. Photography played a distinct role in romanticising these big game hunting adventures.

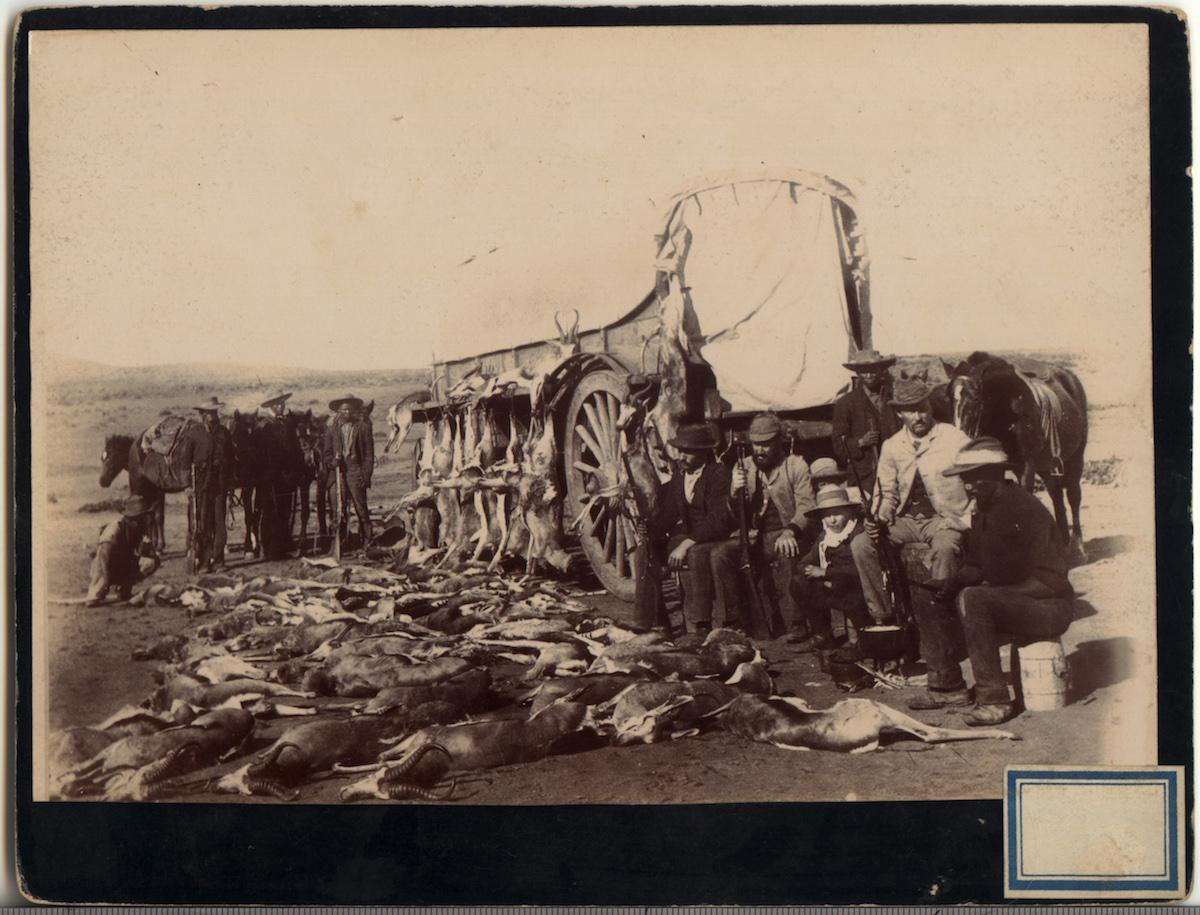

Local hunters. More than 25 springbok carcasses. Children were involved from young. Photograph circa 1880s. Photographer unknown.

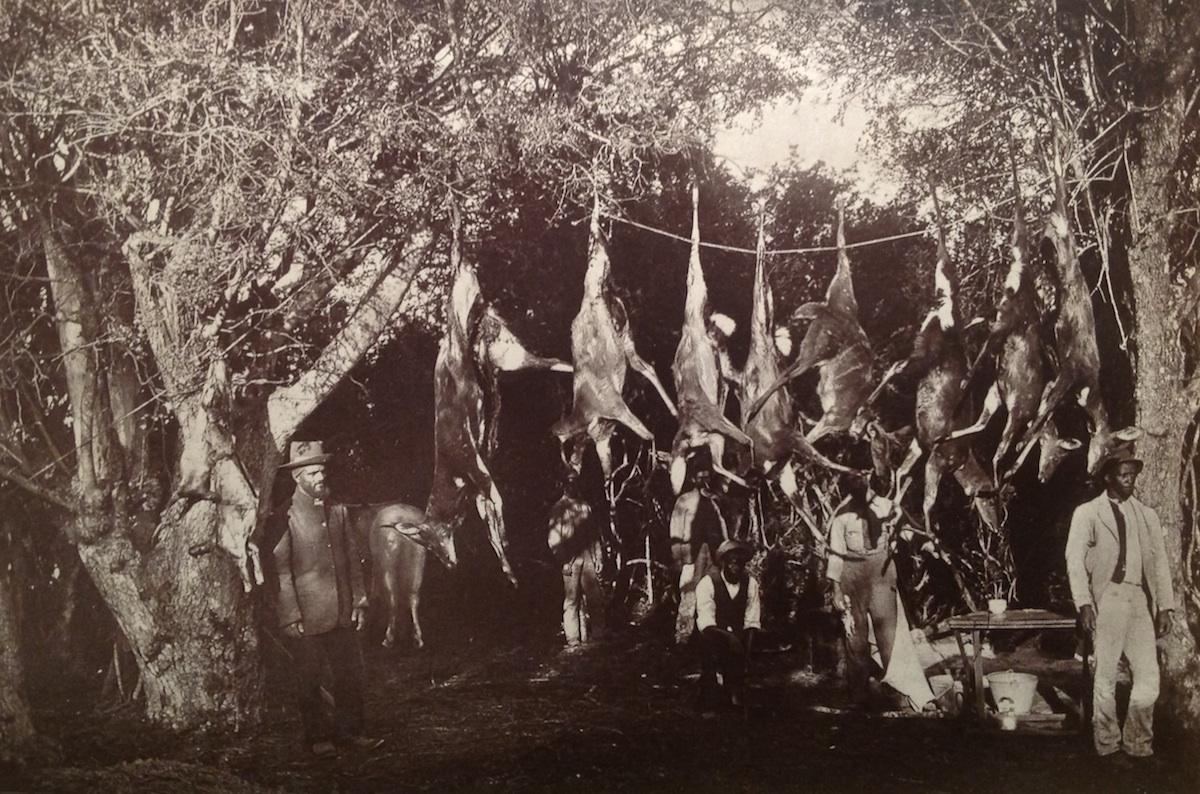

Local hunters showing off the biltong (meat hanging to dry). Photograph circa 1880s. Considering the red cross armband worn by one of the individuals on the photograph, this was probably taken during a military campaign.

Much can be revealed about the individuals and cultures that practiced hunting activities during the 19th century. It is not only a matter of the relationship between humans and the wild-life, but also the different stances taken for example by local populations who largely hunted for food in a sustainable fashion versus the upper-class Europeans who hunted mainly for the adventure and commercial reasons. In many instances, there was also a strong social aspect involved in these hunting expeditions.

The local ethnic groupings also did not have fire arms during the early to mid-1800s, resulting in them being able to hunt with greater skill compared to the European hunters, by using traps, bow and arrows, spears or clubs to kill animals.

Many of the European hunters took their adventure a step further by taking their prey to taxidermists, resulting in countless antelope head and horns that adorned the homes of these colonial sportsmen. Birds were mounted as fire screens, rhinoceros hide covered trays and tables whilst animal skins served as rugs, with or without mounted heads displaying a snarling row of teeth.

One author suggested that large scale hunting was about a deep-seated need for the early colonial hunters to prove their manliness.

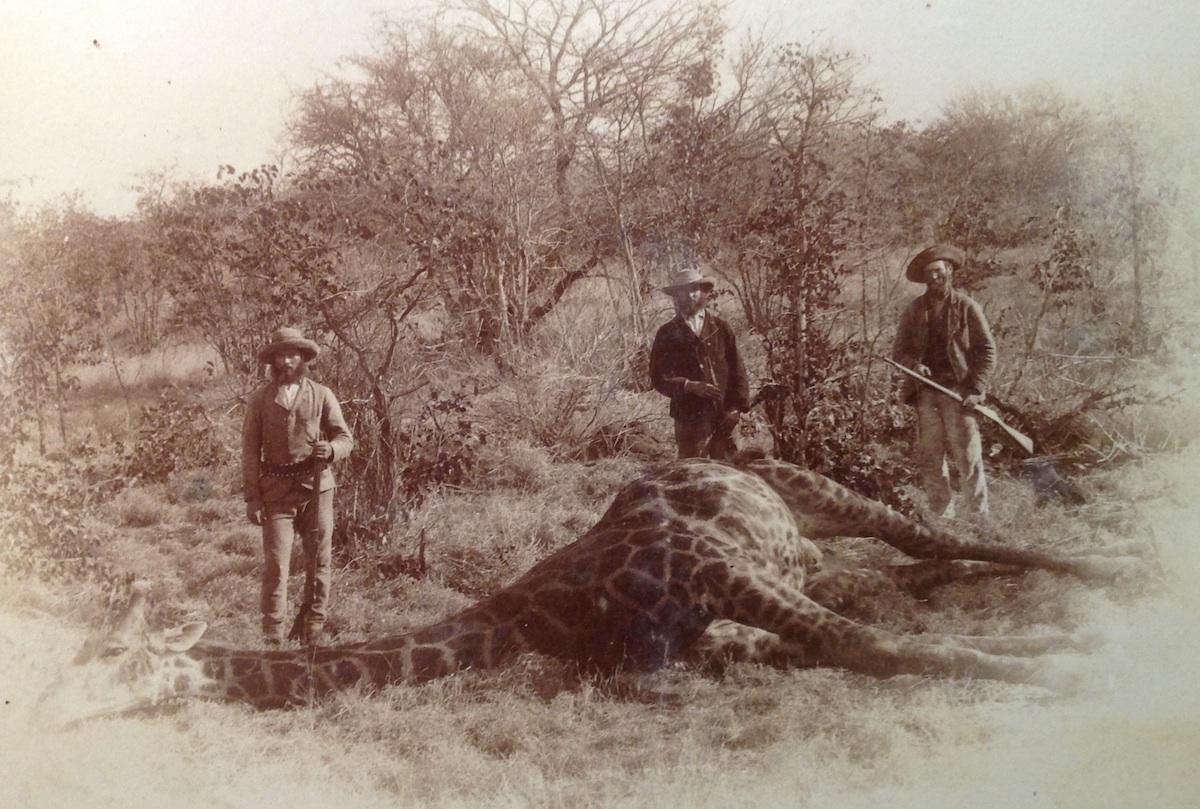

Giraffe shot as a trophy by a foreign national. Circa 1885 – Photographer unknown.

No record exists of female hunters in South Africa during these earlier years.

During 1864, one hunter describes his experience as follows: “...discovered in the Western Free State a wealth of game such as I had hitherto read about in books but had never believed.”

Hunters needed a memento – Something a photograph would capture best.

Whether big game hunting, fishing or simply shooting for the pot, some hunters ensured that their success was duly captured photographically – be that in the open or in a studio. These images became important mementos when sharing many creative versions of their hunting expeditions.

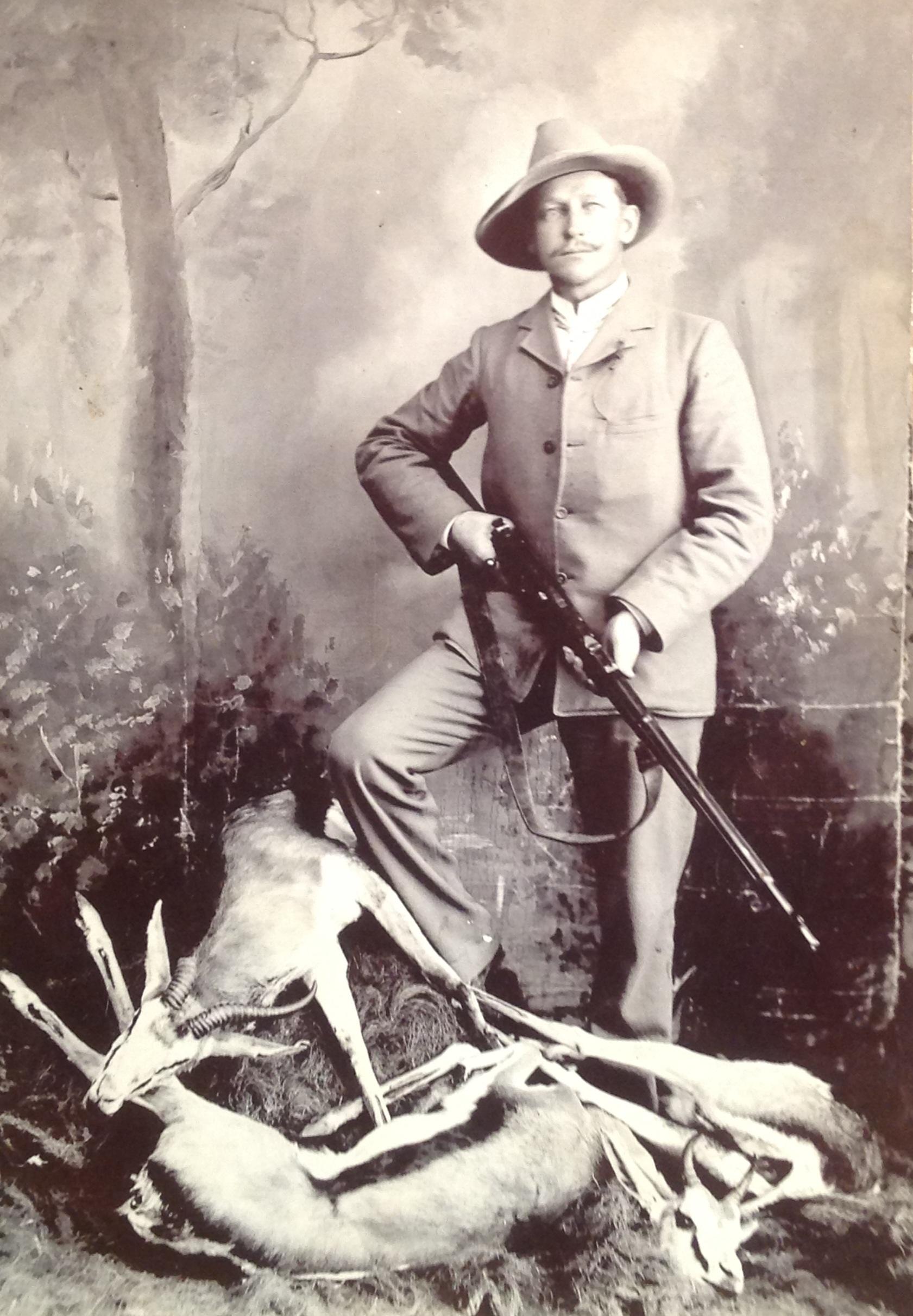

After a day out hunting, some hunters saw it fit to drag the carcases of animals into a formal photographic studio setting to have their images captured as souvenirs of their success in the veldt.

Local hunters after a day out. Image, taken in a studio, shows around 12 springbok and duiker plus a number of pheasants held by the hunters. Photographer unknown (Circa 1885). Cabinet format photograph.

A German national who took 4 springbok shot after a day in the veldt into a Rouxville studio in order to ensure he retained a souvenir. Cabinet card photograph Circa 1907. Photographer: L Friedenthal.

Elephant trophies were popular with the European hunters in that, amongst other, elephant heads were mounted as wall decorations, the feet were used for cigar boxes, umbrella stands, footrests and wine coolers whilst hooves served as inkwells.

Records exist of some of the earlier hunters that shot more than 1000 elephants in their lifetime – one hunter killed 200 elephants within a 9-month period resulting in a total ivory haul of five tons.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, elephants were protected in the Cape. A £20.00 licence was required to proceed in the shooting of an elephant.

To be cornered by a wounded elephant had severe consequences. Fabb (1987) reflects on the death of one Cobus Klopper. The elephant drove his tusk through the hunter’s body and then proceeded to trample him beneath his feet whereafter he lifted the hunter’s body with his tusks and threw the body into the thorny veldt.

Similar stories exist of hunters being killed by rhinoceros.

Captain Crozier with an aartvark. Circa 1900. Taken by an unidentified mission photographer. Image on a glass slide found amongst mission related photographs.

Several hunters and adventurers published books following their African adventures. Some of these were:

- William Charles Baldwin (1826–1903) - an English born big game hunter who wrote about his hunting adventures prior to 1861. African hunting: from Natal to the Zambezi (published 1863);

- William "Old Bill" Finaughty (1843–1917) – South African by birth (Grahamstown) – is believed to have killed over 400 elephants in his life. His book is titled: The recollections of William Finaughty - elephant hunter 1864-1875;

- Roualeyn George Gordon-Cumming (1820–1866) - a Scottish traveler, sportsman and big game hunter who killed numerous game including lion, leopard, white & black rhinoceros, buffalo, giraffe, various antelope, hippopotamus, 105 elephants and even a rock python. During 1850 he published an account of his time in Africa titled: Five years of a hunter's life in the far interior of South Africa;

- Major Sir William Cornwallis Harris (1807–1848) an English military engineer, artist, naturalist and hunter. Although prior to the era of commercial photography, he published an account of his time in southern Africa: The wild sports in southern Africa (1838) and a folio volume containing lithographs: Portraits of the game animals of southern Africa (1840);

- Frederick Vaughan Kirby was a soldier, traveler, big game hunter who hunted extensively in the eastern Transvaal until the Anglo-Boer War. Two books were published by him, namely: In haunts of wild game (1896) and Sport in east central Africa (1899). Kirby later became the superintendent of the Transvaal Museum's zoological gardens until 1907. Post this period he was making a living by selling birds and mammals to museums and private collectors, which confirms an additional reason around the commercialisation of hunting.

Local hunting party showing off their 8 bushbuck and 1 jackal shot. Taken at Wycombe Vale in the Eastern Cape (1888). Photographer: Port Elizabeth based Robert Harris.

Easter hunt – Eastern Cape. Bushbuck ready for the slaughter. Note the skinned carcass on left of image (1888). Photographer: Port Elizabeth based Robert Harris.

A Hanoverian hunter, Herr Eduard Mohr of Bremen, visited Natal on-route to the Victoria Falls during 1869. He, like so many other wealthy European hunters, packed his trophies in cases and returned them to Europe. In one photograph, Mohr is seen posing with several trophies, including a hippo skull.

The cost of such expeditions was high and only the well-to-do could afford an African safari, which would involve several month’s travel in the bush. Preparation was like a military expedition. Bearers and guides had to be hired. This not only created employment opportunities but provided food for the local population. It was the job of gun bearers to clean and skin any game shot as well as look after the guns of the hunters.

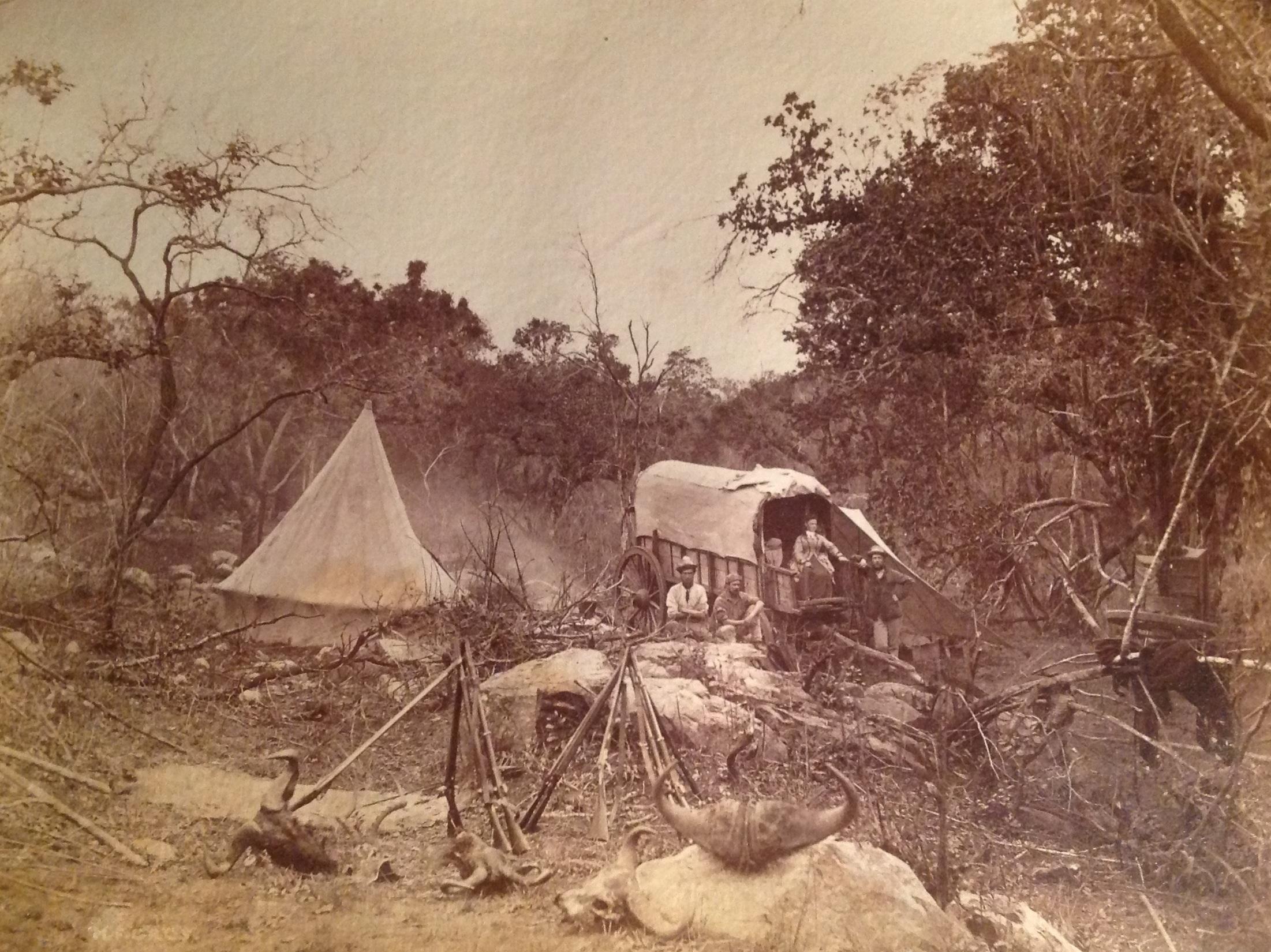

Tents were required for the hunting party – this would include a tent for dining, skinning, bearers etc. Regular mention was also made by foreign big game hunters on the indispensable assistance rendered by the indigenous hunters accompanying them on their hunts.

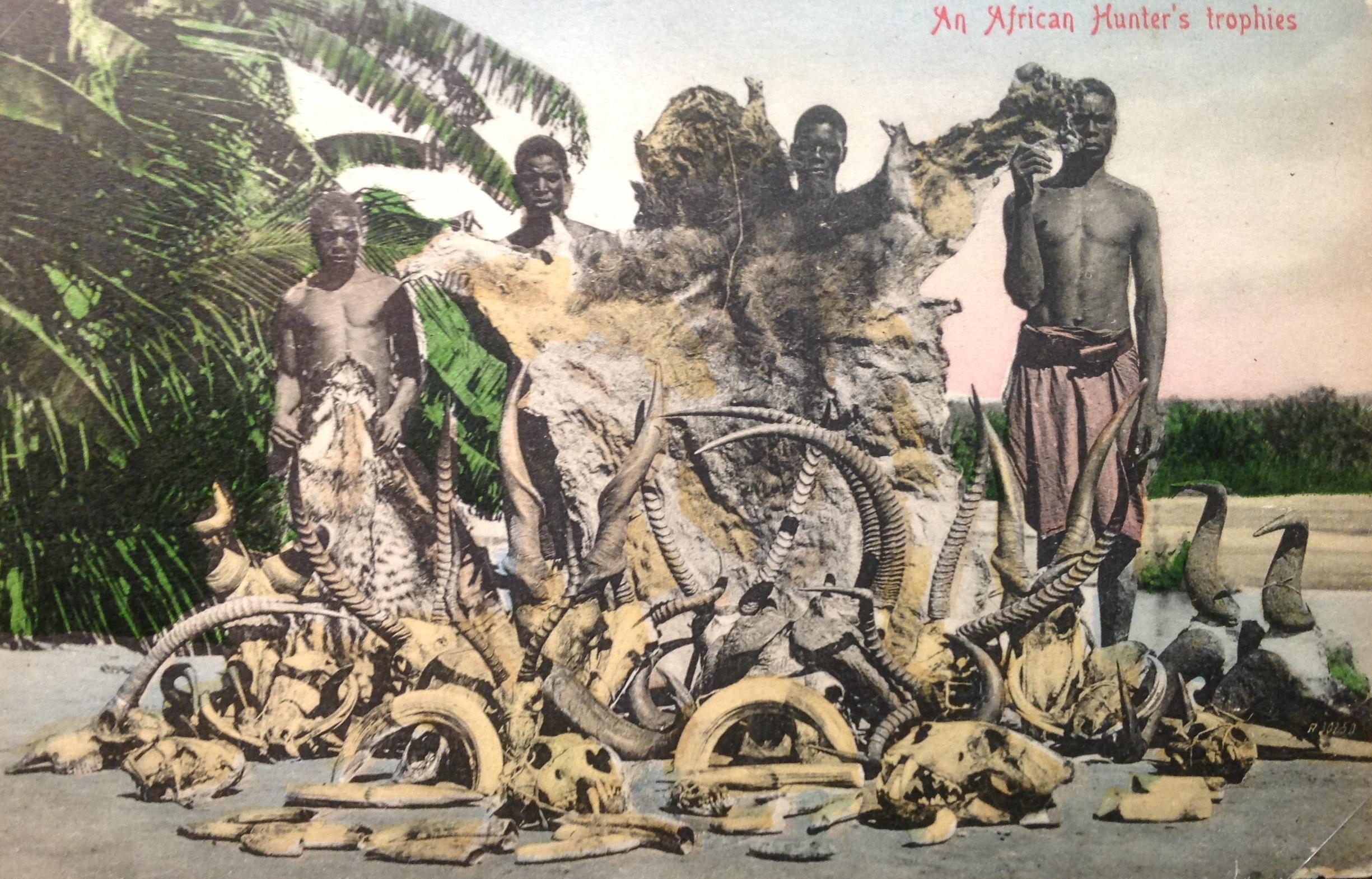

A picture postcard image produced by Sallo Epstein (Circa 1905), showing off a huge variety of animals hunted down, namely lion & leopard skins and skulls, Sable antelope, Waterbuck and Eland horns etc.

Prior to 1910, motor vehicles were not in general use in Africa, resulting in hunting parties tackling the tasks on foot or horseback.

What has been described as “sustainable hunting” started when the Voortrekkers started moving north. Early South African hunting legends included individuals such as Jan Viljoen, Petrus Jacobs (see more below), Hendrik van Zyl and Piet Botha. The author has not come across any photographs including these individuals in that they were less likely to pose for the camera compared to their European counterparts. Being used to life in the open veldt, they had less to prove by posing for souvenir images.

Other local hunters at that time included:

- Cigar – South Africa’s own 19th-century Griqua elephant hunter, who first hunted elephant for William Finaughty during 1869. Cigar clearly left an impression with many foreign hunters he engaged with in that he has been referred to in several publications.

- Henry Hartley (1815–1876) although born in England, he became a South African farmer and hunter. It has been recorded that he shot between 1,000 and 1,200 elephants in his life. Hartley eventually died from injuries caused by a rhinoceros collapsing on top of him after he had shot it.

- Petrus Jacobs (born around 1800) was described by Frederick Selous as "the most experienced elephant hunter in South Africa." Jacobs is believed to have killed between 400 and 500 bull elephants, mostly from horseback but also on foot. Jacobs is also said to have killed over 100 lions. Badly mauled by a lion when Jacobs was around seventy-three years of age, he was back on his horse again two months after the incident.

HF Gros photograph of a hunting camp. This image was probably taken during his tours of the Transvaal during 1888/1889

Photography out in the veldt certainly did not go without it challenges in the earlier years. Photography then would have been cumbersome in that the photographer needed to have all the chemicals and bulky development equipment on hand. Bryden (1893), the author of Gun and Camera writes about the difficulty in developing the glass negatives due to the filthy (muddy) water obtained from rivers. He however adds that tents made for ideal darkrooms at the time.

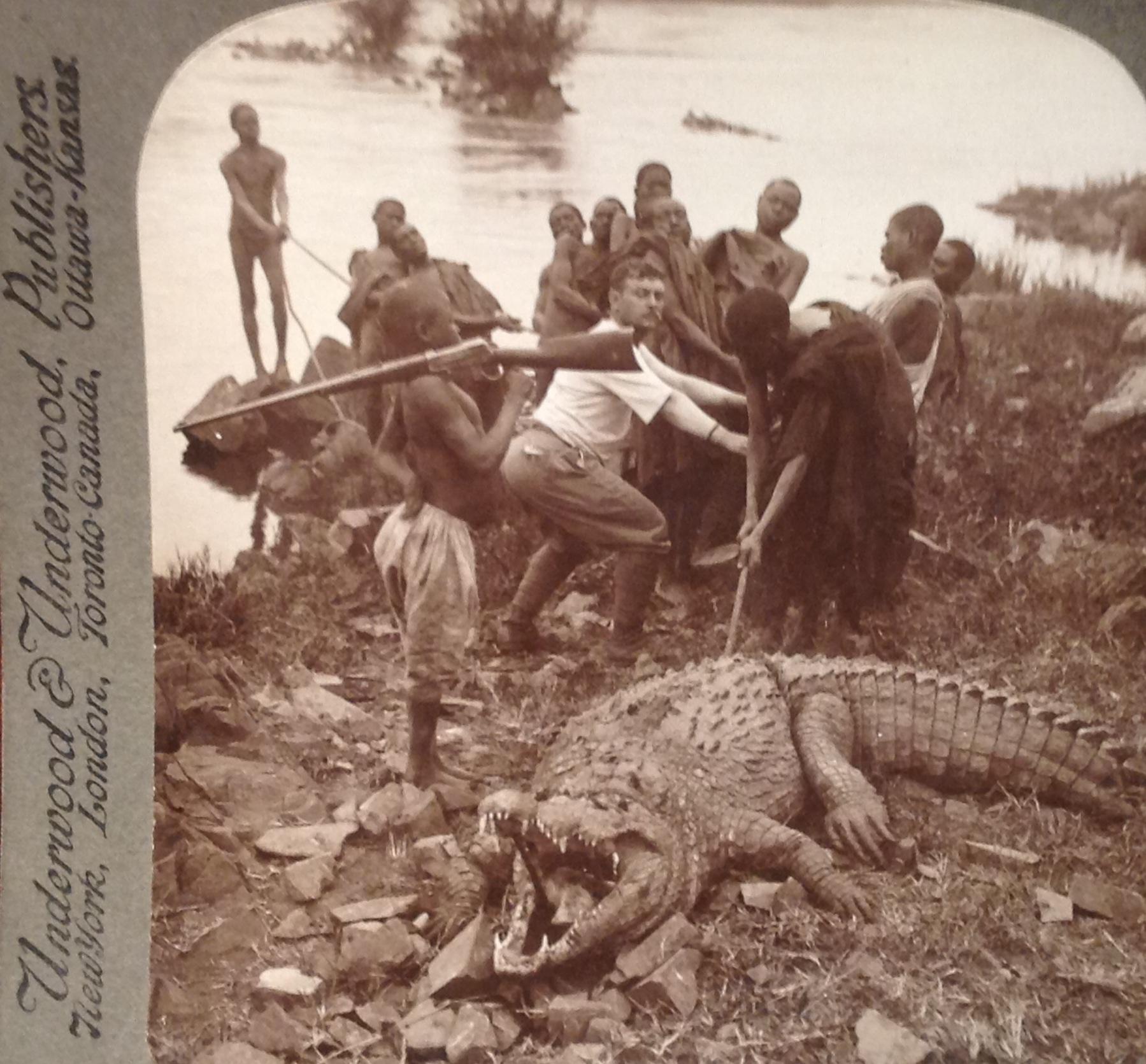

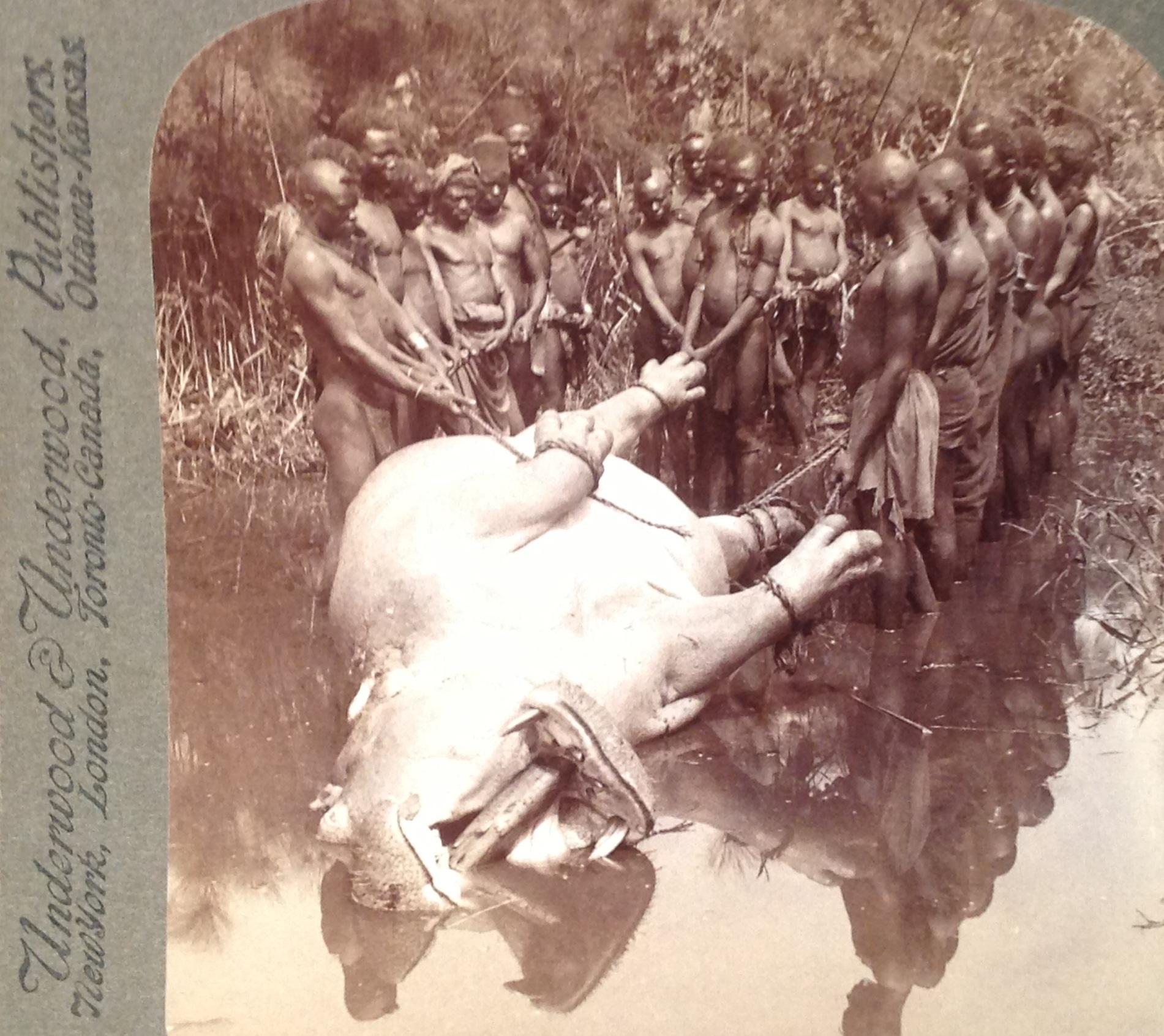

Considering todays squeamish and protectionist standards, some slaughter scenes photographed make for rather gory viewing.

Although photographers and the subsequent photographic images created an exotic context and visual interest in hunting, these images were not necessarily aesthetically pleasing. The startling detail they contained enlarged the realm of the visible, in that most viewers of these photographic images would have been based in Europe and would therefore never have seen or experienced South African wild-life scenery. Images of hunters with their prey is the ultimate photographic realism – where the moral stance around hunting and the hunters was unlikely to be questioned.

The curious question remains however – Why did hunters go through the effort of having themselves photographed with their prey?

The author acknowledges that the reasons would have been diverse, but that it was ultimately about the hunters that wanted an idealised image of themselves – a souvenir. A deeper lying reason was that the photograph also provided a vision of heroism.

All the images included in this article, except for two, have been extracted from the Hardijzer photographic research collection.

Underwood and Underwood Stereo photographs – Circa 1910. These images were produced in bulk. When viewed through a stereo viewer a three-dimensional image would be seen. Although killed for meat by the local population, Hippopotamus’s were not popular trophies for the Europeans.

About the author:

Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Beinhart, W. (1990). Empire, Hunting and Ecological Change in Southern and Central Africa. Past & Present (No. 128).

- Bryden, H.A. (1893). Gun and Camera in Southern Africa. E. Stanford. London.

- De Beer, M. (1992). A vision of the past – South Africa in photographs (1843 – 1910). Struik. Cape Town.

- Fabb, J (1987). Africa – The British Empire from photographs. Batsford ltd. London.

- Harris, R. (1888). South Africa - Illustrated by a Series of One Hundred and Four Permanent Photographs.

- Mackenzie, J.M. (1988). Hunting and Conservation - The Empire of Nature: Hunting, Conservation, and British Imperialism. New York: Manchester University Press.

- Schoeman, K. (1996). The Face of the country – A South African family album (1860 -1910). Human & Rousseau. Cape Town.

- Sontag, S. (2002). On photography. Penguin books. London

- Verbeek, J. & Verbeek, A. (1982). Victorian and Edwardian Natal. Shutter & Shooter. Pietermaritzburg.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_hunter

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_big-game_hunters

- https://www.africahunting.com/threads/history-status-quo-of-recreational-hunting-in-south-africa.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.