Emily Hobhouse died in 1926 in London. The Manchester Guardian carried a substantial obituary which featured her humanitarian work in South Africa during and after the Anglo-Boer War. However, her obituary in The Times (of London) saw her as a propagandist and agitator of note and attributed the woes of the Boers in the concentration camps between 1900 and 1902 to the ignorance of the Boers themselves. This contrast in obituaries highlights the controversy that surrounded Emily Hobhouse in death as much as in life. Emily Hobhouse was cremated and the South African government took custody of her ashes. Her work in South Africa was appreciated in the country that adopted her as its own heroine. A commemoration service was held in Bloemfontein and her ashes were placed in a niche at the base of the obelisk of the National Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein. Emily was British and an honorary South African citizen. She was supposedly quickly forgotten in Britain. I am not so sure about this assertion.

I don’t think Emily Hobhouse was ever forgotten in South Africa and her memory became part of oral family history of a people severely impoverished by a tactic of war that was barbaric and at the time was recognized as a crime against humanity. I have always known of the story of Emily Hobhouse and her work as a publicist, social worker, relief organizer and pacifist. To me she was a heroine who featured in the oral history of our family, because my grandmother, Dorothea Barbe, was interred in the concentration camp in Bethuli and her family suffered grievously. When I was growing up my mother in turn told me about her mother’s war time experiences and why this one woman was indeed a compassionate figure who. Here was a brave heroic and strong woman who spoke to and for a people oppressed by the catastrophe of war.

This book is about that one woman and the concentration camps which she came to investigate. She strove to improve ordinary living conditions but also to write about and expose those conditions and the suffering and fatalities that resulted. She was a woman who stepped out of her class and the interests of her country and her name became synonymous with the exposure of the concept of the concentration camp as a crime against humanity.

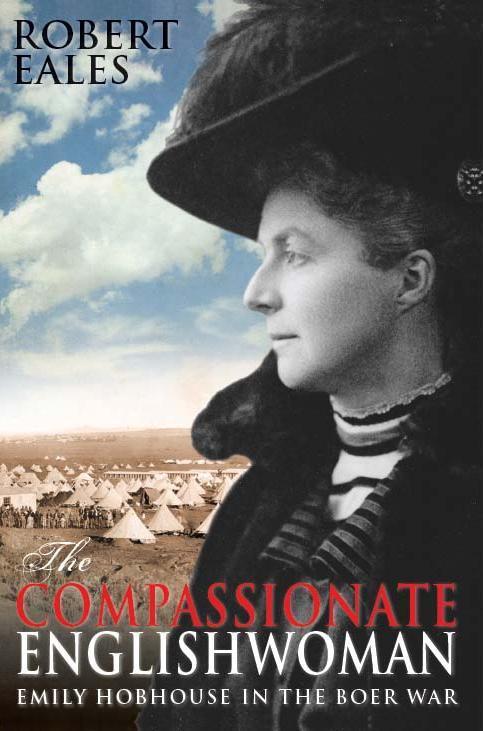

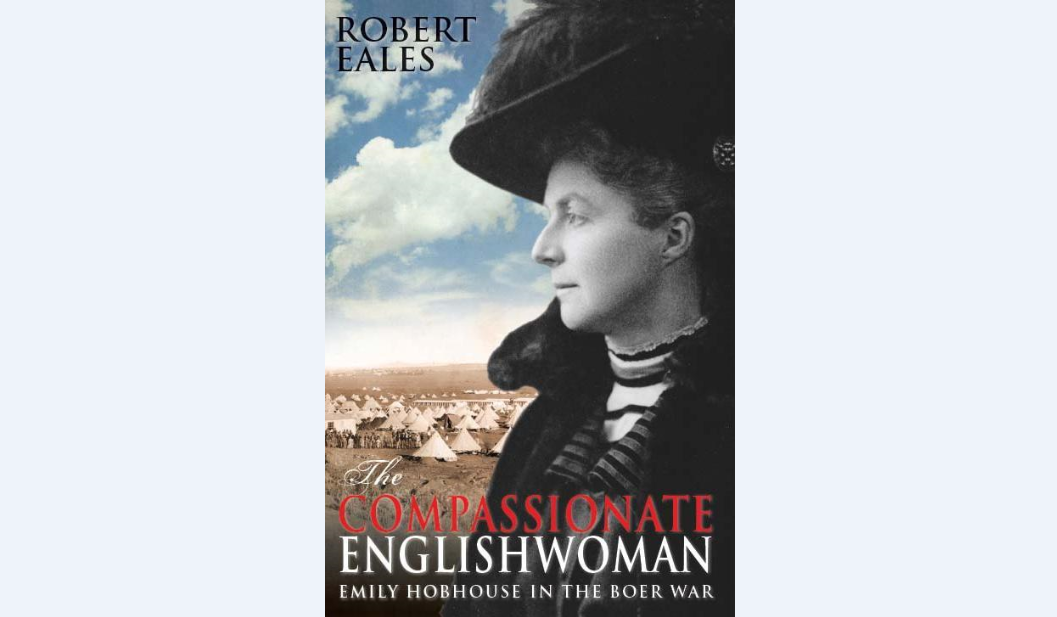

Book cover

The South African concentration camps were established as a tactic of war by the British generals, who after 1900 were surprised that the Boers did not surrender but switched to guerrilla tactics following the fall of Bloemfontein and Pretoria. The policy of the British military, of Kitchener and Roberts, was slash and burn, laying waste to farms, homesteads, and a seizure of cattle and horses, implements in an effort to clear the land of farms, and people and extinguish all signs of life. The objective was to prevent the Boer commandos being supplied and provisioned by the farms and in so doing bring the war to a speedier end.

Memorial Stones at the Irene Concentration Camp (The Heritage Portal)

The term concentration camp came to take on a very different meaning some 40 years later during the upheavals of Hitler’s Germany and the Holocaust. The Germans pointed to a British precedent but here sins of commission and omission have been confused. The British did not set out to kill women and children in the concentration camps of the Free State and the Transvaal. It was through ignorance, poor management and a flawed strategy that high mortality, disease and untold suffering to the point of the virtual destruction of a nation happened. The objective was not to deliberately kill women and children. The fatalities of the camps was a by-product. There are two components to this history - the camps and the woman who made a difference.

An original gravestone from the Irene Concentration Camp (The Heritage Portal)

Robert Eales in a scholarly well researched work published by UCT press in 2015 and reprinted twice in 2016, retells the story of Emily Hobhouse and her role in the Boer War and how she found herself on the wrong side of British history. The focus is on the dramatic highlights of the period 1900 and 1902. I would have liked a fuller biography. The approach is strongly narrative with Eales competently drawing upon earlier biographies (the Fisher biography in my opinion is still worth reading), and a range of primary and secondary sources, including the unpublished Hobhouse draft autobiography held in the Bloemfontein State archives.

Eales has an easy readable prose style and drops the reader right into the action of war, when in December 1900, Emily Hobhouse arrived in Cape Town at the start of a mission to learn about the concentration camps and what could be done by a single woman supported by the humanitarian South African Women and Children Distress Fund in England. Fund raising was then directed to delivering practical aid to women and children placed in unsuitable unhygienic camps by the British military. What is fascinating was that Hobhouse managed to get the support and permission of Milner to travel north to visit the camps in person. Eales quickly places Emily Hobhouse in her social milieu and explains her origins in a chapter that could have been sharper in explaining the origins of the Hobhouse mission and the roots of her anti-war views. Hobhouse travelled north by train and Kitchener took over from Milner but was more cautious in allowing Emily only to investigate as far as Bloemfontein.

The key to understanding Hobhouse was her pacifism. She was a highly political lady and perhaps did not understand the enormity of her daring. One becomes absorbed by the story that Eales tells of Hobhouse and her visits to the camps for white Boer families. She observed what was happening, came up with practical suggestions to address issues of sanitation in the high death rates among the children in particular. Soap, water and cooking facilities were essentials and not luxuries in these barren canvas tented camps. Even more significant was Emily’s writing about what she saw, writing letters to her politically well positioned family and ultimately getting many issues published. She remained in South Africa for approximately 4 months and returned to England to tell her story. Of course she was not believed, but she had set off a hornets’ nest. Her criticism of the living conditions and the suffering endured by women and children could not be ignored.

Eales introduces us to the official reports on the camps that began to make their appearance in 1901, for example Goodwin’s report on the white camps in the Transvaal. Then came the Turner report followed by the Trollope report. The question here is whether official knowledge of conditions in the camps was being generated ahead of Hobhouse’s reportage. Hobhouse was a political novice and the publication of her report on the camps changed her life in totally unexpected ways. She brought down the wrath of empire and Westminster on her head and sparked official responses that countered her assertions. Hobhouse countered with a speaking tour of England that took her from Oxford to Bradford, from Bristol to Sheffield, despite the press attack and public vilification. By July of 1901 the Minister of War came up with his own plan to have the camps investigated and Hobhouse discredited and hence the work of Millicent Fawcett who set off for South Africa to discover the “facts”. Eales though sees the work of the Fawcett committee through the eyes of Hobhouse, though they produced a 200 plus page report that confirmed many of Hobhouse’s findings.

Emily Hobhouse attempted to return to South Africa in October 1901, but her arrival turned into a farce and fiasco for by this time Kitchener and Milner knew their enemy and were determined not to allow her to set foot on South African soil. She was speedily dispatched back to England on the next ship. Eales draws the conclusion that stopping Hobhouse at all costs was imperative for Kitchener, Milner and Brodrick who would face disaster if the British public came to understand what had been wrought in the concentration camps in the name of war.

Eales has a useful chapter on the documentation of the British concentration camps for black and whites. There are some discrepancies in the number of camps depending on the source used. There are two invaluable maps showing where these camps were and listing the names of the camps for black and whites. One criticism that seems to creep into discussion is that Hobhouse was more interested in the camps for whites than those for blacks. This allusion needs more discussion because of context and to extend current historiography. An appendix of concentration camp occupation and fatalities rounds off the story.

The Boer War ended on 31st May 1902 and the question that must be asked was did the concentration camps work as a strategy. Did the war come to an end sooner because of the suffering and high fatalities of women and children or did such barbarity simply harden attitudes of combatants? Did the Boer men ultimately wish to sue for peace because of what their families were enduring or did the women urge their men to continue the struggle because of their suffering? These are the tough questions which need probing. Eales succinctly addresses the facts about mortality and moves on to the issue of culpability for the human tragedy to the Boer nation. Kitchener, Roberts, Lansdowne, Broderick, Milner, Salisbury, Chamberlain and Balfour were all guilty of pursuing policies and practices which were inhuman and inhumane.

Names of those who died at the Irene Concentration Camp (The Heritage Portal)

The crux of the matter comes down to whether all tactics of warfare are to be permitted on the ground that firstly it is impossible in 20th century warfare to separate civilian loss from military engagement. The deeper questions are about the changing nature of war and the impact of industrial technology on a modern armaments industry. I would have liked a discussion on what really was the significance of the concentration camps as a tactic of war and whether a single individual has the right and moral authority to challenge the decision by a sovereign state to make war on another. These are the issues of our own time as much as they were a century ago.

There are actually two parallel themes in this book - the tale of the Compassionate Englishwoman, Emily Hobhouse and on the other hand, what happened in the concentration camps and its relevance today. Eales sticks with the story of Hobhouse as a figure in her own time and the moral dilemmas are only hinted at. What was so remarkable was that she was English and hence she belonged to the enemy. That in itself points to the transcendence of pacifism and what happens to people who ascribe to a pacifist viewpoint in times of war.

The legacy of the Boer war was devastating in its reach and impact. The war impoverished a nation and meant that the challenge of the new South Africa was to reconcile English and Afrikaner in a new national entity. This was how Smuts saw his mission. As great a tragedy was the neglect of the relationship of black and white South Africa and the failure to force a common identity for all.

Emily Hobhouse returned to South Africa after the Boer War and attempted to introduce a textile industry to give the women of the post Boer war territories new skills and crafts. Not a bad idea though not particularly successful. My own grandmother perhaps absorbed something from that effort as she supported her large brood of seven children with her sewing machine and all her life sang the praises of Emily Hobhouse.

It is perhaps unfortunate and unlucky for Rob Eales that a further new book on Emily Hobhouse has been published in August 2016, the book by Elsabe Brits “Emily Hobhouse, Beloved Traitor”. This later book offers another biographical interpretation. But both books are worth reading and I shall review the Brits book in a later review article.

I strongly recommended this thought provoking read.

2016 Guide Price: R345 from all leading booksellers (published by UCT Press)

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.