Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Johannesburg is a gold mining city and, through the decades, there have been a number of disasters related to the industry. A walk through Johannesburg's cemeteries offers a visual history of premature loss through mine related explosions. The granite memorial in the Braamfontein Cemetery erected in memory of those who lost their lives in the great dynamite explosion of 1896, is still moving and offers a unique insight into Johannesburg history.

The memorial to those who died in the disaster (Kathy Munro)

The memorial takes us back to one of the earliest and most tragic mining disasters in the city's history. On 19th February 1896, a freight train left stationary on a siding at the then Johannesburg Railway Station (it was in Braamfontein and today is known as the Braamfontein Station) carrying dynamite exploded. The train comprised of eight trucks of dynamite (Norwich says ten) or 2300 wooden cases adding up to between 56 and 60 tons of dynamite (AP Cartwright gives the statistics of 3000 cases of blasting gelatine amounting to 80 tons). The trucks had been left standing in the sun for three and a half days (why is a crucial question) and, when a shunting engine was backed into these trucks, the impact apparently caused the dynamite to explode in the hot afternoon sun (is this the only plausible explanation?).

NZASM 40 Tonner locomotive being recovered at Braamfontein after the explosion

The explosion blew a crater measuring 250 feet long by 60 feet wide and about 50 feet deep (see main image). The estimates of the number of people killed vary from 75 to 130 with over 300 people injured. The Obelisk records 75 dead while The Star reported 78 fatalities and four boxes of remains. The exact number of casualties will never be known. It is also estimated that between 1500 and 3000 homes were destroyed. I find it fascinating that different sources quote different statistics for deaths, injuries, losses of homes, size of the crater and so on.

In early 1896 Johannesburg was a young mining town emerging from mining camp status. While newer permanent businesses, office blocks, retail shops, clubs and hotels were being built in downtown Johannesburg, and the newly acquired wealth showed in bricks, mortar and ornamental masonry and iron work, many of the homes of ordinary workers were very temporary, speedily erected, almost jerry built structures. They were made of wooden timbers and corrugated iron, perhaps some rough locally made baked clay brick walls. Many were no more than cottages or shacks.

Houses destroyed in the Braamfontein explosion

The houses in and around the station, in Braamfontein and the surrounding suburbs took the brunt of the explosion. It was reported that every window in the centre of Johannesburg was blown out. Chimneys ended like forlorn relics sticking out from the soil. The iron rail tracks were pushed up and suspended at crazy angles. Railway locomotives were derailed or destroyed. Hedley Chilvers describes “a vast black and gold cloud rising like a colossal mushroom into the blue.” Debris then fell to earth, a mix of body parts, horse remains, earth and iron fragments. Injuries were caused not only by the explosion but by the subsequent disintegration and collapse of masonry, timber and iron sheets. People of all races were killed and most deaths were women and children. Many were poor people from the nearby suburbs of Newtown and Fordsburg, the locations of Brickfields (one can position the locations on the 1896 map) and Braamfontein itself. The horse and animal carnage must also have been immense. The impact of the explosion was felt miles away and the sound of the explosion heard some 10 to 200kms away (again a vague range).

The time of the day was unfortunate, as in the mid afternoon while the menfolk were at work, the women and children were at home and hence casualties were unusually heavy among the families. Limbs were dismembered and bodies were unrecognizable such was the impact. Rescuers wept as they gathered up the bodies of young children. Nothing remained of the loading clerk Dirk of Doornfontein, tasked with the job of offloading the trucks.

Those are the bare bones of the story but what struck me was the lack of exactitude on the figures and numbers. One needs to probe further. Any bit of history is made up of the details of what happened (almost the micro picture) and then broader canvas asking about why this explosion happened (the macro scene).

A dynamite cartridge with the Alfred Nobel signature

Some Economic and Financial History

If one wishes to understand why this explosion happened in 1896, one needs to delve into some complex economic and financial history in Europe and then turn to the local scene to begin to understand why an explosion in Johannesburg in Kruger’s Republic happened. On the surface it was just an accident and accidents happen but there might be something more here.

Strangely I lived at the Modderfontein Dynamite Factory as a child between 1949 and 1957 and my father worked at the factory for decades. As a child the fact that there had been an explosion in Johannesburg in 1896 was part of my oral history. We lived in a disciplined combination of village and workplace factory. The hooters at the factory signalled dangers, risks, ends of shifts and explosions. At the factory, explosions were rare events but they did happen and like a mine community everyone shared in the loss when someone was killed. One would hear the deep thunderous rolling sound and then that loud cacophony would die away to silence and an ominous sulphurous cloud would mushroom to the sky.

But let us get back to the basics. Alfred Nobel was the Swedish chemist who came up with two significant inventions. The first being the invention of the detonator patented in 1864 using a percussion cap which enabled a controlled explosion of nitro-glycerine. The second was the invention of Dynamite which was a combination of nitro glycerine mixed with a porous silicate (a diatomaceous earth) called kieselguhr. The substance was then poured into cylinders. This made for far safer transport, and more stable explosives for civil engineering, mining and military use. His inventions were patented and within 10 years there were 16 explosives producing factories in 14 countries including France, USA, Finland, Austria, Scotland, Germany, Spain, Italy, Portugal and Hungary with Nobel as shareholder or co-owner. During the 1870s Nobel developed three new explosives - gelignite, gelatine dynamite and blasting gelatine.

South Africa from the 1860s was simply a market for dynamite following the establishment of diamond mining in Kimberley. Gold mining on the Witwatersrand from the mid-1880s offered a larger and even bigger market. The story of the establishment of a dynamite industry to supply the mining sector is a convoluted one revolving around state concessions, monopoly, contracts, royalties, dishonesty and corruption. Early efforts to establish a local gunpowder factory by Alois Nellmapius under Kruger’s concession system failed, but the demand for dynamite once the Rand mines took off was exponential. Dynamite initially came by ship to the ports and was then transported by wagon to the Transvaal. In 1887 Edouard Lippert, a German immigrant businessman was granted a 16-year contract to establish a company and a factory to manufacture local explosives but in the interim to have the monopoly on imported supplies. French bulk supplied explosives were locally packaged in cartridges and on sold to the mines with about a 100 per cent profit margin.

It has been argued that local mining interests lobbying for British government intervention to lower dynamite prices was one strand in the deteriorating relations between Uitlanders and Kruger’s Boer republic in the early to mid-1890s. The Lippert contract was cancelled in 1893 and both French and German governments added their protests on behalf of the Nobel factories. In the background, secret Nobel trusts had created a monopsonistic (a single) supply situation. The solution for the Transvaal Volksraad was to turn the manufacture and sale of explosives into a State monopoly in 1893. Middlemen and shrewd negotiators made a fortune creaming off commissions and royalties; government benefitted from import duties and pay offs. All this was to be a temporary situation because in 1894 a new company was formed with a mandate to build a new factory on the farm Modderfontein 12kms northeast of Johannesburg. Dynamite factories were at that time located in remote isolated open places because of the risks inherent in production and the dangers of explosion

An early view of the Modderfontein Dynamite Factory (from the AECI Dynamite Company Museum)

This was the origins of the Modderfontein Dynamite Factory, initially making use of imported raw materials. Cartwright explains, that “To manufacture one ton of explosives at Modderfontein in 1896 it was necessary to import four tons of raw materials”. There was still a conflict of interests, as a nascent local factor was in competition with sharp dealing importers. The Chamber of Mines articulated the voice of the mine owners who wanted the cheapest possible supplies whether locally produced or imported. The very uncertainty about the future lifespan of the mines made Max Philipp, the chairman of the new 1894 company (grand title of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Fabrieken voor Ontplofbare Stoffen) seek short term profits (keeping more profitable imports going) over long term investments (there was the commitment to build a factory). Franz Hoenig the first factory manager was given the task of building a factory and embarking on serious production of dynamite. The Chamber of Mines was interested in local production and not just packaging and bringing down the price of a case of dynamite at the shaft. The first Transvaal manufactured blasting gelatine to be turned into cartridges was produced on June 29th of 1896.

Frans Hoenig Haus (The Heritage Portal)

Intriguing Questions

Hold the story right there. The importance of this background becomes apparent. If the dynamite explosion happened on 19th February 1896, was it local or imported dynamite that exploded? Here is the first puzzle. It seems that the dynamite that exploded (and hence the claim that the fault actually lay in the instability of imported German nitro-glycerine which had been imported in bulk between 1894 and 1896) was just a matter of shaping the substance into the cartridges and that this happened at Baviaanspoort (the original 1887 Lippert plant). The cartridges were then dispatched to Lippert’s magazine at Auckland Park (not that far distant from the Braamfontein station).

The second conundrum is precisely where did the explosion happen. The Star (Like it was, 100 Years in Johannesburg, 1987) describes the location as “a few hundred metres from the town Centre” but comments that “the curious thing is that today nobody is sure where the actual site was”. Leyds in his history of Johannesburg (1964) includes a map and pinpoints the site of the great dynamite explosion as at Old Kazarne, located effectively at the end of Diagonal street and close to the Coolie Location (now Newtown). Beavon (2004) identifies the site of the explosion as the “western spur near the Johannesburg Station” and cross references back to an 1897 Plan of Johannesburg”. Chilvers (Out of the Crucible, 1929) says the explosion occurred “close to the bend of the railway line between Braamfontein and Fordsburg and opposite Vrededorp”.

The 1896 plan of Johannesburg displayed below positions the station in Braamfontein and shows the proximity to the three nearby locations and Brickfields. Note from the map the size of the street stands and note the Braamfontein Cemetery was already in existence – it was Johannesburg’s cemetery for the burial of everyone.

1896 Map

Regardless of whether this was local or imported dynamite the third question is why did the explosion occur? Apart from the possible instability and a defect in production of the dynamite, was the cause the heat of the sun, the length of time the trucks had been left in a siding, the impact of a shunting engine, a defect in the manufacture of the dynamite? Again why was the cargo left standing for three days.

It is time to introduce William Hosken, a colourful early Rand pioneer whose name survives in the name of a prominent company, Hoskens Consolidated Investment Company listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Hoskens was an immigrant Cornishman who had represented the Nobel interests in Johannesburg and was himself heavily involved in mining activities. Hoskens first opposed the Lippert Concession and then at the instructions of the Nobels withdrew his opposition (and was handsomely rewarded), but by 1895 switched back to opposing Lippert and joined the Reform committee prior to the Jameson Raid. Hoskens owned storage magazines too and Lippert used these storage facilities when his own magazines were full. Lippert now no longer used the Hosken storage. These circumstances explain why the railway trucks loaded with dynamite stood in the sun for the several days. Hence Chilvers (1929) argues for a link between the cause of the dynamite explosion and the Jameson Raid.

The Aftermath

A Commission of Enquiry was appointed to probe the possible causes of the disaster. It sat for days, but the men who knew the most about the logistics of transport, sidings and shunting instructions had been blown up. An overseas expert from Glasgow tested and examined other dynamite cases that had not exploded but were from the same batch. Experiments with temperature up to 140 degrees caused no other samples to explode. Damage was estimated at 1 million pounds and at the time the NZASM (the railway company) was immediately held liable. Safety was not yet a science. Railway trucks were also a relatively new technological advance and carried the volatile cargo. So was the explosion caused by inept logistical management by the shunter and the impact of one truck against another? Eventually the Commission could find no identifiable cause of the explosion.

A disaster relief fund was immediately established and raised an immediate 60 000 pounds which grew to a sum of 130 000 pounds. A camp was established at the original agricultural show grounds to the north (roughly in the vicinity of Helpmekaar schools near the Braamfontein Spruit) and one source recounts that 89 000 meals were served (J G Blumberg account). These funds were used to quickly reconstruct the homes lost. The unidentified bodies were laid out at the Wanderers Club. The Club was turned into an emergency hospital.

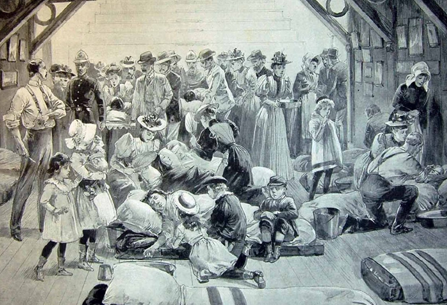

Sketch showing the Wanderers club turned into a hospital - Illustrated London News March 21 1896 (print for sale on Amazon)

The Illustrated London news for 21 March (just a month later) shows a sketch meant to solicit sympathy and convey the mood. President Kruger visited the injured and saw the site of the explosion and he too wept when he saw the children. Queen Victoria telegraphed her deepest sympathies to President Kruger and the news quickly spread around the world to be reported in newspapers in Australia and New Zealand.

In the aftermath of the explosion, there was a frenzy of building activity in Braamfontein to rebuild the cottages and homes to rehouse people. Glass was in particularly short supply. It was a time when Johannesburg people pulled together and hence the memorial we see today in the Braamfontein Cemetery to remind us of that terrible event.

1896 is described by Hedley Chilvers in his book Out of the Crucible as the most disastrous in the history of the goldfields. The Jameson Raid had played out unsuccessfully a few months earlier and many of the plotters were still incarcerated. Another disaster with South African connections was the loss of the ship, The Drummond Castle which sank off the coast of France in July 1896, with only 3 survivors (of 245 on board) and many Johannesburg bound passengers were drowned. The ship had sailed from Cape Town and was bound for London. 1896 was the year of the Rinderpest and agricultural ruin. 1896 was also the year of the Matebele Rising in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia for Cecil Rhodes) with significant losses in war of both black and white, the revolt by Lobenguela was sparked by the very collapse of the Jameson Raid.

Oscar Norwich’s book, A Johannesburg Album, included two postcards of the crater (page 142); such was the impact and the newsworthy element to this explosion that picture postcards were printed. The post cards themselves became valuable documentary history (see main image). There are some excellent contemporary photographs of the explosion posted on the Flickr website by Hilton T (click here to view) showing roofs blown away, rafters destroyed, or tin shack houses now just a heap of twisted metal. Hilton T has also included a couple of eyewitness accounts but has unfortunately not included a source reference.

The memory of the Great Dynamite Explosion was seared into Johannesburg’s record and its history. In the Chilvers book, there is a black and white sketch by William Timlin, done in 1929, imagining the smoke cloud spreading skyward after the explosion. The event had the power to inspire even later artwork of homage. In 2012 the artist Eduardo Cachucho created a Looking Glass painting, a collage of images laid over that giant crater. It is a subject that fascinates if the images to be found online are a pointer. However to me the most moving memorial (and it seems to be the only memorial) in Johannesburg is the Braamfontein cemetery obelisk.

IN MEMORIAM. This monument is erected by the subscribers to the Dynamite Disaster by the subscribers to the Dynamite Relief Fund to the memory of all those who lost their lives from the Dynamite Explosion at Braamfontein Station on February 19th 1896. The number who met their sad death from this cause, both whites and coloureds, was 75.

_____________________

Requiescant in Pacem (may they rest in peace )

Today now 120 years later as we commemorate the greatest of Johannesburg tragedies, we remind ourselves that gold mining, coal mining, platinum mining, asbestos mining and phosphate mining are all endeavours requiring guts, determination and heroism plus capital, brawn, labour and organisational skills. Suffering too often stalks the lives of the miner. Yet the lure of mining wealth and desperate poverty draw both legal and illegal miners to prospect and to mine. Today around the Witwatersrand, the illegal miners or zama zamas descend underground to search for the scraps of still to be found gold bearing ore in worked out mines. They to endanger their lives and often there are deaths. Safety in organized mining is a top priority and the safety records achieved have improved remarkbly over the years. Accidents still happen, the earth beneath our feet is not always stable and dynamite to blast tons of rock remains essential.

The early transport of dynamite (source unknown)

References

- A P Cartwright: The Dynamite Company (1964)

- Hedley A Chilvers: Out of the Crucible (1929)

- G A Leyds: A History of Johannesburg (1964)

- James Clarke: Like It was The Star, 100 years in Johannesburg (1987)

- O Norwich. A Johannesburg Album – Historical Postcards (1986) p 140 and 142

- Anna Smith: Pictorial History of Johannesburg (1956) p 47

- For Map: see reproduction on the DW of Anna Smith: Street Names of Johannesburg (1972)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.