Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

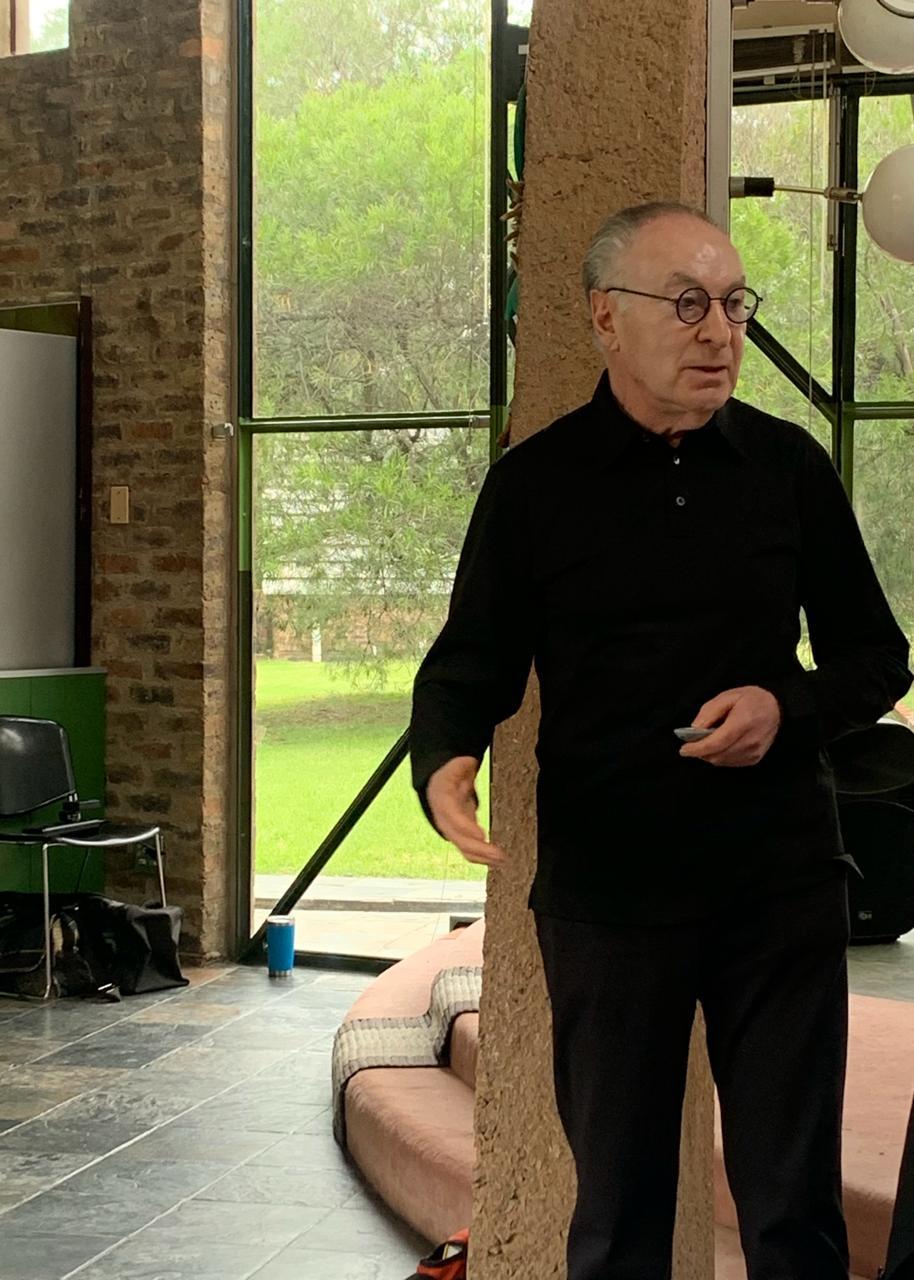

On 28th February, a remarkable reunion took place between architect and client - Saitowitz the architect and Brebnor the client, at the newest of Wits University’s properties. The event was a workshop at a rural retreat named Brebnor House at the President Park Agricultural Holdings in Midrand. We were at a house that dated back to 1976 when a young Stanley Saitowitz became the architect for the young Linda and Scott Brebnor who wanted to build a home of their own.

Scott Brebnor House or Transvaal House (Stanley Saitowitz - Natoma Architects)

Some 48 years later, architect and client, now both older men with full lives and careers met again at a Wits symposium to reflect and share their vision, the creative process and their experiences shaped by the construction of this now iconic house. The audience of Wits academics and colleagues were the invited guests to share a poignant encounter. It was a day for listening to the key presenters, good conversation, and posing questions. The hopes and new aspirations of younger people raised some interesting questions and lively discussion.

Sharing a poignant encounter (Kathy Munro)

It was an event that challenged the boundaries of heritage. This house is an expression of modern architecture and yet it is now an iconic admired work of architecture that could and should be labelled “heritage”.

Conversation and reflection led me to think about the flexible / elastic meaning of heritage. Heritage can be culture, custom, tradition and shifts from the tangible to the intangible. Heritage need not have a date - heritage can be recent buildings as we recognize worthy structures that command enduring attention. We were here to celebrate good architecture; architecture that broke boundaries and marked a moment of change and predicted the future.

House Brebnor‘s significance has been written about in the literature.

Saitowitz himself recognized the significance of this house in a book: A House in the Transvaal in a series by the Harvard Graduate School of Design and published by Princeton Architectural Press in 1995. His own reflections are contained in an essay, Architecture as Human Geography, a wonderful piece on context and the recognition of Ndebele mud house design and construction. (As an aside I was delighted to now have the signatures of Saitowitz and Brebnor in my copy.)

The Brebnor House is a landmark structure. We were in in the space and place and with those complex contradictory questions about South Africa’s past, its built environment, and the diversity of influences. We seek to find a modern, some would say authentic, vernacular in South African idiom in architecture, but we realize how hard dialogue becomes when the colonial is rejected as transformed architecture is desired or demanded. The central question then becomes was House Brebnor an expression of the past or is House Brebnor a pointer to the future.

Window detail (Kathy Munro)

The location of the house is President Park and it still has the letters AH attached. The greater area is Midrand but it was once called Halfway House. AH stands for Agricultural Holdings. In decades past folks who wanted to live in the country and perhaps keep chickens and pigs and ride horses would pick their plot. There were few houses to purchase so people built their own. In the 1970s this Brebnor’s land holding was a six-acre plot. The name Halfway House (in place until 1981) said it all – a peri urban locale, halfway between Johannesburg and Pretoria. In 1981 Halfway House became the independent municipality of Midrand but was incorporated into Johannesburg in 1994. A local website describes the appeal of country living: “homes here are set on sprawling small holdings in an area that still has a distinct atmosphere of 'country' about it.” But change is evident as developers look for opportunities to build town house complexes. Today, as one turns off the M1 Motorway, the first imposing building encountered is the Mizamiya Mosque. An alert flashes when one passes the Central Park Apartments on Bandroad – suddenly Midrand is densely populated and the rural ambience is fast disappearing.

Hence the determination of Dr Heather Dodd to save the Brebnor House when it became known to her that Scott Brebnor needed to downsize. Heather was the link between Stanley Saitowitz and the Brebnors and through goodwill, generosity and cooperation Stanley Saitowitz and Linda Brebnor contributed the funding to enable the Brebnor house to be gifted to Wits’ School of Architecture in 2023.

The whole area is now much more developed: tarred roads, neighbours, it is more built up – it is still rural but hardly agricultural. There is a giant pothole on the tarred road and even to gain access one must identify oneself at the security box at the access entry point to the suburb.

The first impression of the house is of a series of circular tunnels, a mix of glass and walls in complex geometric form that could be a green house, a bomb shelter perhaps or sun capturing sanatorium. It is more than a shelter on the veld of what was once the remoter edges of city. At first sight one is puzzled, second glance communicates that this is a house but a most unusual one that challenges all preconceptions about the usual four walls, roof, front windows, and a roof making a house. Immediately one wants to know whose house this is and where did all these different ideas originate.

Oblique view of the covered patio (Kathy Munro)

An unusual house challenging preconceptions (Kathy Munro)

Yes, it is a house but one of the most extraordinary houses that I have visited. It is a house of contours and circles, earth anchored as roof touches ground. This house is an expression of creativity, partnership and confidence of the owners. It reveals the trust between Scott and Linda Brebnor and their architect, a very young Stanley Saitowitz. This house was a self-built project; the owner Scott worked to the designs of the architect Stanley.

Although constructed some 48 years ago, it is a heritage property that Nnamdi Elleh and Heather Dodd recognized as demanding preservation. The hungry hand of the developer looking for land to build cluster housing at Midrand had to be pre-empted. Stanley Saitowitz, born in 1949 and a student at Wits in the early 1970s, left South Africa in 1978 to study for a master’s degree abroad. Chipkin in Johannesburg Transition described him as part of the South African diaspora in North America. His work in South Africa was limited to just two houses – House Brebnor and Norman Catherine’s house, Fook Manor, at Hartbeespoort Dam. It is remarkable that an architect who was still completing his first degree in architecture should have notched up two significant houses. He was destined to find fame in the USA.

Today Saitowitz is an acclaimed architect for his multiplicity of designs that combined prefabricated units and advanced engineering technology that could be combined in a variety of ways for pod housing, offices, or student housing. Natoma Architects have designed some extraordinary structures in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Florida, Philadelphia and elsewhere. Chipkin realized that it all started in the Transvaal and that these houses became “...a source of regional identity for some in a rising generation in the 80s. In some respects, they were proto-Californian houses – significant for an architect now famous in San Francisco.”

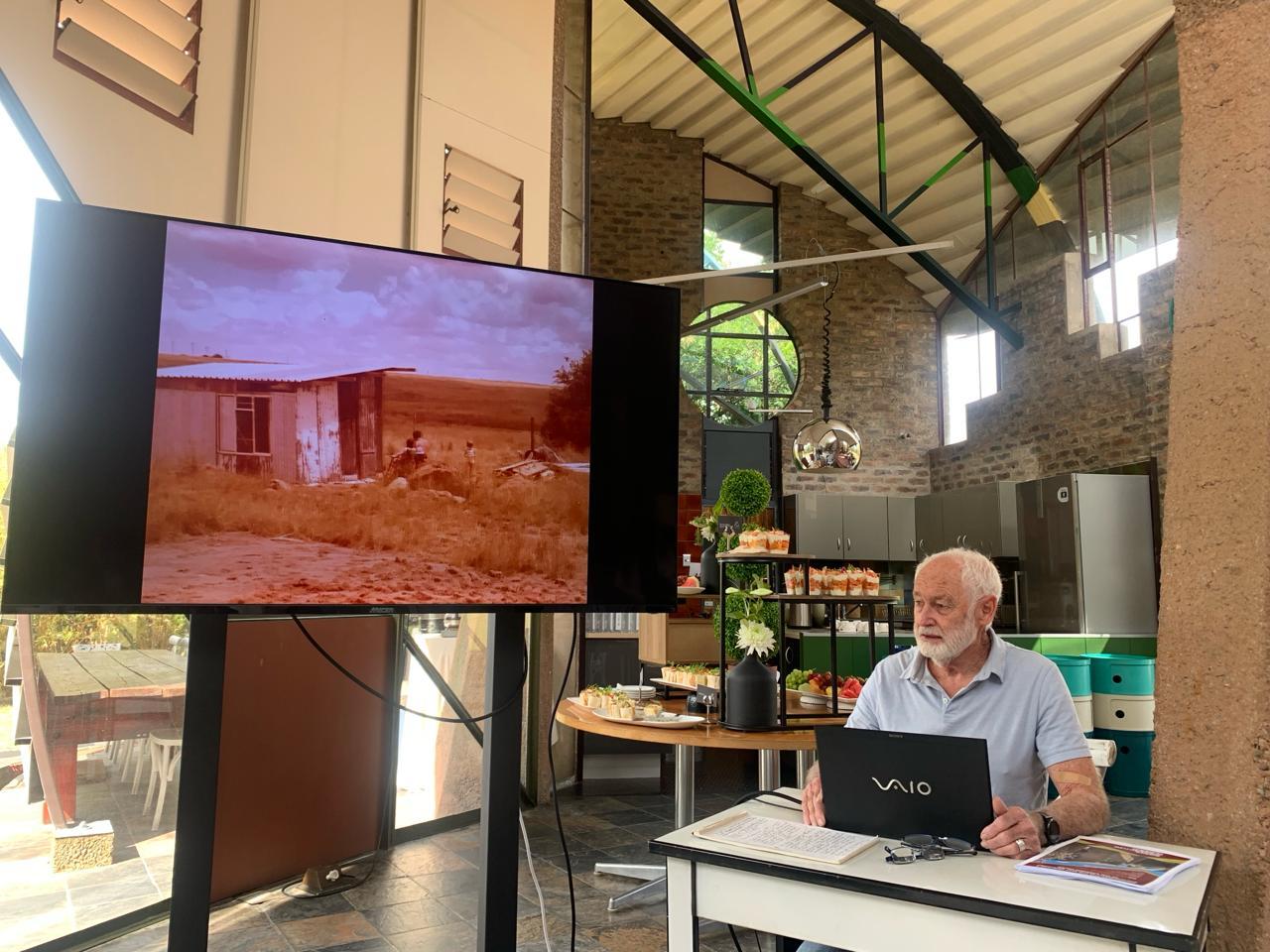

Prof Elleh handled introductions. A presentation by Stanley followed on the evolution of his career. Scott talked about his early years on his remote country property and how he knew he had to build his own house and how he came to meet Stanley Saitowitz. Conversation between Scott, Stanley and Heather took off and lively debate and questions followed.

Stanley Saitowitz (Kathy Munro)

Scott Brebnor (Kathy Munro)

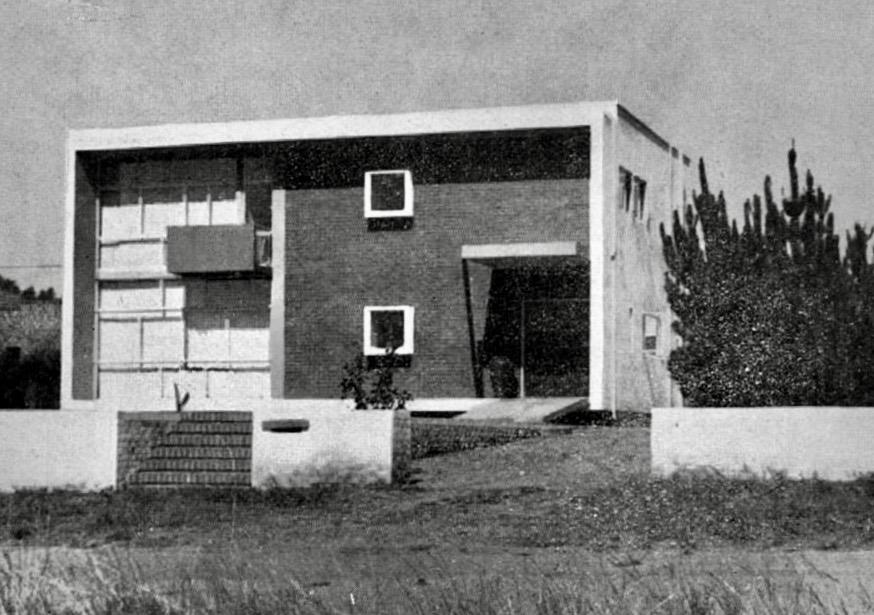

Stanley reflected on his upbringing in Emmarentia. His parents owned a house in Emmarentia in Komati Road and Stanley’s memories from his childhood were of new homes appearing in the fifties in the then rather new suburb and the impression made by the then new Emmarentia synagogue. As a child he was aware of construction possibilities as he marvelled at the creative process; as a building team worked, a liveable house could appear within months – the product of design and physical labour. He was inspired by the Rex Martienssen House in Greenside – a modernist house designed and built by the architect for himself and his wife in 1939; it all linked back to bringing Le Corbusier to the Transvaal with the 1930s Transvaal Group of architects themselves inspired and committed to international modernist design.

Martienssen House

Stanley went on to study architecture at Wits in the early seventies and it was men such as John Fassler, Reg Rippon, Mike Lazenby, Revel Fox, Ivor Prinsloo and perhaps most importantly Pancho Guedes who inspired and influenced the young Saitowitz. Pancho Guedes, of Portuguese origin, had been a major player in Lourenco Marques (Maputo) until he came to Wits as head of the school of Architecture in 1975 and enthralled a generation of students.

Wits School of Architecture (The Heritage Portal)

Stanley visited Maputo with Pancho and the Smithsons (the London star architects Alison and Peter) who visited the Wits in the seventies. The architectural education of the 70s decade was rich in multiple platforms and student participation in educational symposia and their own publications. Students were alive to the possibilities of new materials and diverse opportunities. They worked in studio groups to create and energise one another. Stanley mentioned the lightbulb moment of seeing images of the remains of structures on the terraces of Machu Picchu; it had been a sophisticated city built on the contours of a mountain.

Stanley talks about design principles, the warp and weft of architectural history, an awareness of new building systems and radically different construction techniques, the influence of Ndebele and vernacular design to shape a South African style of design. He reminded us that Johannesburg has a unique beauty in its high-rise super blocks and skyscrapers, densely clustered – a modern recent city rising on the veld. But in days gone by it was all too readily and mistakenly seen as “a white city” when in fact the city was part of a “black city”. He reminded us to look at “the back yard“. In other words, there is another city, a settlement of people who express exuberance, colour and other ways of building houses of mud construction and intense vibrancy of Ndebele art patterns. Boundaries between cultures were and can be crossed with different approaches, expectations and experiences influencing and being absorbed by “the other”. It’s a two-way process of cultural assimilation, integration and regeneration.

The Brebnor House is a masterpiece of architecture built at a moment of time, capturing the sense of place as it was in 1976 when the project started. The design was about contours and the circular geometry. It’s a house that blends with the landscape of rocks, grass, and red highveld earth. The curved roof that reaches to the ground, channelled the heavy summer rain into a deep channel repeating the pattern of the roof and carrying storm water back to ground. It is remarkable that so little has changed – the house remains as it was conceived and constructed in the 1970s – a home for two people (there is just one bedroom and one bathroom).

All about contours and circular geometry (Kathy Munro)

It was a unique partnership of the architect, Stanley Saitowitz, and the clients, Linda and Scott Brebnor. Stanley had recently graduated from Wits, he was young and new in the architectural profession. Scott was a draftsman for a mining house and Linda was an academic in the field of genetics at Wits.

The mid-seventies were a time of turmoil in Johannesburg with the Soweto uprising of 1976, but the Brebnors had confidence to purchase a piece of open veld at Halfway house) to live a life of closeness to the veld; a place of wild grass, rocks, open space and clean air. Outbuildings in the definite shape and form of Ndebele design, plus stables and a cottage in the same idiom were part of the complex. Open veld and huge rocks, hard earth, high grass, indigenous trees and toughened shrubs defined the landscape.

The Brebnors as a young couple wanted to build a home of their own. Scott had sketched some initial ideas. Initially they thought of Stan Field as an architect they could approach. Stan made an impact when he designed the iconic house at Khyber Rock, but Stan passed the Brebnor appeal for help to Stanley Saitowitz. The rest is history.

Miller House, Khyher Rock (Stan Field via Artefacts)

We are witnessing the renewal of almost an act of faith by the client in the architect. Young architect met young client, and both expressed confidence in one another. Who knew then where the future would lead.

Some four decades plus later we are here to understand the house – a house that needs to be read at many levels – the varied influences with the preeminent lineage of African architecture, Pancho Guedes, stretching the boundaries of novel materials. The line ran from Ndebele to European and back to Ndebele. It is a house of adaptability. The kitchen is at one end and opens onto a multipurpose communal living area – “a lapa” which could be a lounge or provide an office space or a symposium or even a theatre.

View toward the kitchen (Kathy Munro)

Innovations involved the use of found objects and second-hand materials, sheet roofing materials, the use of Q – Deck roofing, industrial piping, corrugated water tanks for the shower. There is renewal but also complexity. Stanley spoke of the popularity of writing about architecture in the fifties based on the relationship of Time and Space, but for him his evolving creativity led him to build his designs around Occasion and Place. Technical problems were solved as they were encountered.

Stanley Saitowitz wrote about the Brebnor house in 1985 (UIA International Architect, issue 8 on Southern Africa edited by Haig Beck). Here he described the original concept: “The House began with simulation of the act of habitation on a piece of paper. A circle is marked out on the ground. The Contours – abstracted human dimensions = are terraced into the circle and planted with two alternating strains of grass “.

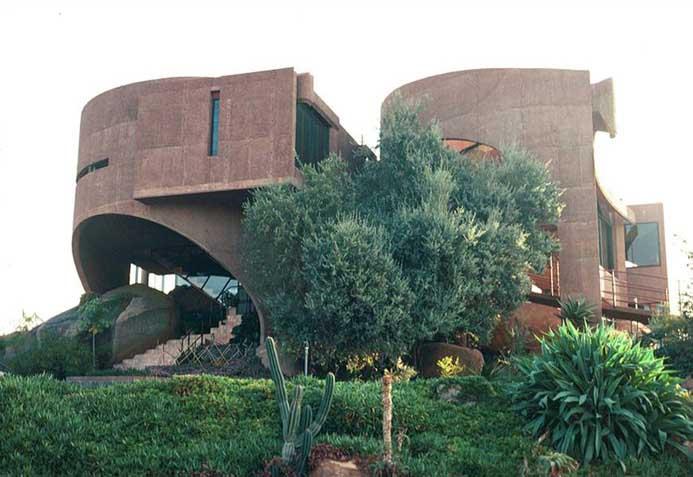

Arthur Barker in an essay titled Stones that Sing (in the book Creating Coromandel by Edna Peres and Andrea Zamboni, Artifice Press, 2023) explores the emergence of regionalism in South African architecture and identifies Stanley Saitowitz’s design for House Brebnor as representing “the construction of a new typography through the direct relationship with the surrounding rocky outcrops”. In the UIA publication Saiitowitz himself commented on the role of the rocks: "The house is a process of making the rocks habitable; the house is a hollow rock”.

It was indeed odd that the Press family chose an Italian architect, Marco Zanuso to design their country house, Coromandel (near Dullstroom) with its echoes of Angkor Wat. The design of Coromandel is also strongly earth bound, organic and natural. It is doubtful that Zanuso read Saitowitz but I could indeed see parallels between the ideas behind Coromandel and House Brebnor.

Coromandel

Another interesting comparison is the Pancho Guedes barrel vaulted house designed for the Cohens in Forest Town, a property that has recently been sold to new owners by the Marcus Holmes estate. All these examples engage with a sense of rootedness in an African space.

Now four decades later, the Brebnor house is still worth examining, the ideas dissected and the influence and long-term impact of the creation and partnership.

Stanley Saitowitz, Heather Dodd and Scott Brebnor - moved into conversational mode, recalling the past, exploring cultural links and influences. The idea of building and living in one’s own house was and still is a powerful almost primal motivator. I identified with that: it is something my own father wanted to do in Kew but never accomplished.

Scott Brebnor has lived in his home which he built himself, using the Saitowitz plans, for 43 years. The question came up about climate and coping with summer and winter temperatures of the highveld (yes, the house can be cold in winter) but it is a house that merges seamlessly with its environment.

Stanley also talked about the house he designed for the artist Norman Catherine, Fook House. It was fascinating to be given a taste of Stanley’s later houses in California – such as the Sunlight House. In a later lecture delivered at Wits in the evening, Saitowitz took us on a journey through his American ouvre and his approach to design and construction – thickened walls, pods, stacked town houses, student housing and the concept of building blocks that could be adapted and applied in multiple ways with an awareness and sensitivity to site, context, adaptability to make houses and homes for living and working.

It was a privilege and an honour to participate in an extraordinary day. We enjoyed a unique experience of a symposium that brought architect and client together again. Here was a friendship forged in a common purpose over four decades ago. These are lives well lived leaving a legacy that becomes a heritage saved, preserved, and celebrated. I marvel that both Stanley and Scott are together again reminiscing but with no nostalgia but rather a pride and wonder for what House Brebnor stands for. Four decades ago, the house was out of the mainstream, today it is a case study and an expression of the roots and trends in modern architecture, the inspiration for others and a forerunner of the Saitowitz career in the USA. It is a house that elevates architecture to art.

Main image: House Brebnor (Stanley Saitowitz - Natoma Architects)

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.