Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

On June 19, 1566 at Edinburgh Castle a son was born to Mary Queen of Scots and her husband Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, the baby was christened James and he would become the sixth of his name to be King of Scotland when he was barely 13 months old. His mother was forced by the Lairds to abdicate the Scottish throne and she fled south to England for her own safety and he would never see her again.

James’ parents were both Catholics but he would be brought up as a Protestant and during his boyhood was kept in seclusion, being given a superb education under the tutelage of George Buchanan. During the king’s minority, Scotland was to be ruled over by a succession of regents, four in all, the Earls Moray, Lennox, Mar and Morton, in what were troubled times. On gaining his majority he took over the affairs of state with an eye for what was happening south of the border as he knew full well that he had to keep relations with Elizabeth the Queen of England as cordial as possible, even though his mother was her prisoner. He was as we say “playing the long game” because he knew he had the best claim to the English throne on Elizabeth’s death, by virtue of descent through his great grandmother, the daughter of King Henry VII.

When Queen Elizabeth I died, in 1603, James duly came south to claim the English throne as James I and he would henceforth call himself the King of Great Britain. His succession ended centuries of feuding and fighting between the English and the Scottish (although it continues to this day on the rugby field, the last Calcutta Cup match was a thrilling 38 all draw). Both countries were now under one king although they would retain their separate parliaments until the Act of Union of 1707 was passed during the reign of Queen Anne (the last Stuart monarch). Both countries, since 1560, were staunchly Protestant having gone through the trauma of the Reformation and the breaking away from the Roman Catholic Church.

Portrait of King James

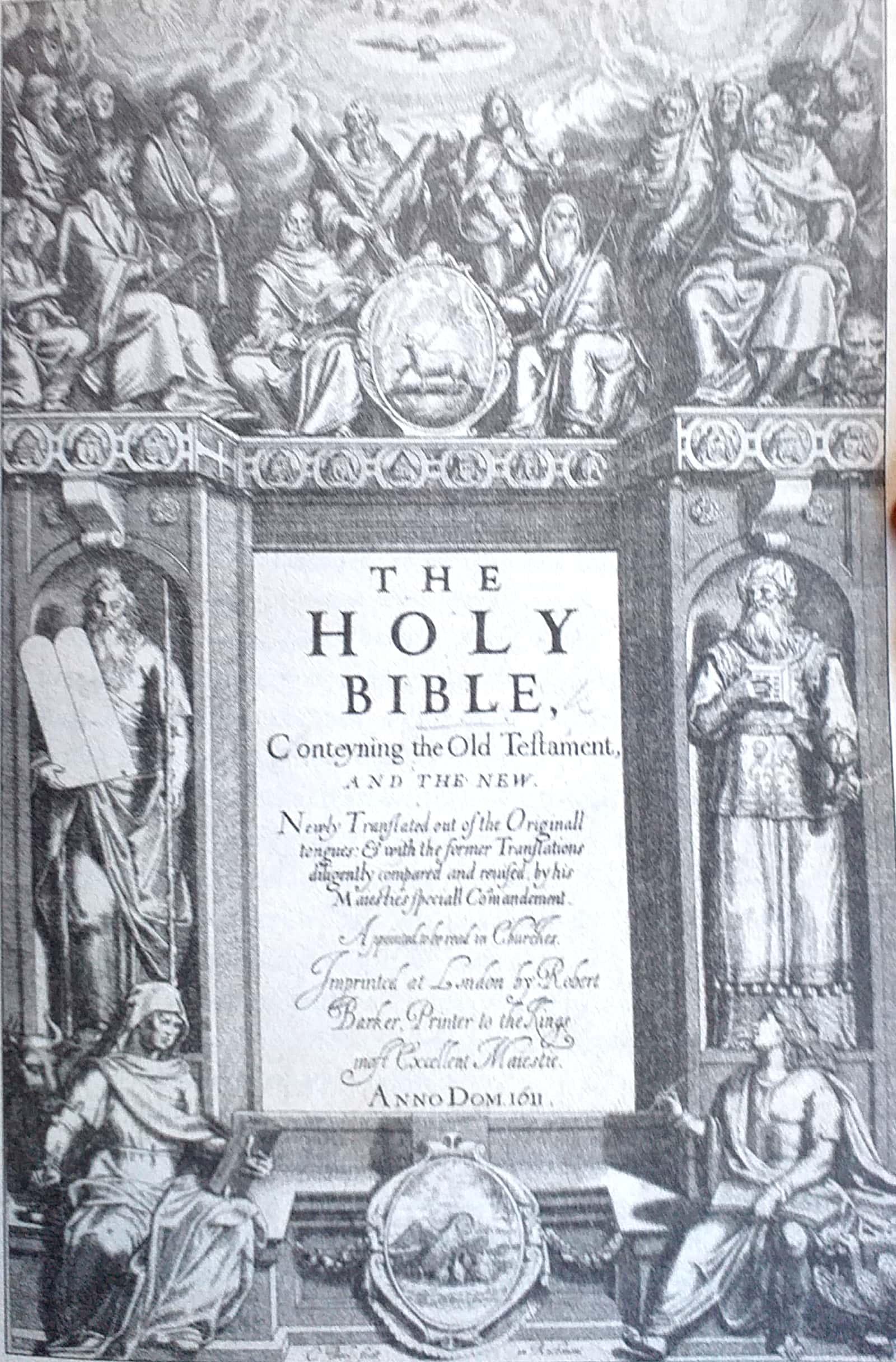

King James’ reign (1603 to 1625) started with great promise as he was a learned man and was able to debate on matters spiritual and temporal and his first opportunity to show his intellect was when he convened a conference (January 1604) to soothe the differences between the Anglican Bishops and the Puritan leaders, but in truth his maxim “No Bishop, No King” showed on which side of the argument he was on, as he had no intention to make fundamental changes to the Anglican church which as king he was the head. As a concession to the Puritans he agreed to a new translation of the Bible which would be the Authorised Version, better known to future generations as the “King James Bible”.

The English Catholics, now a minority, could see that any grievances that they may lay before the king would be summarily dismissed and they made plans to blow up the Houses of Parliament when the Parliament opened on the 5th November 1605. Needless to say the explosion which would have killed not only the King but also all the Lords and the Commoners present never happened as a tip off led to the arrest of Guy Fawkes in a cellar beneath the House of Lords; the 36 barrels of gunpowder that he would have set a fuse to were sent to the Tower of London for safe keeping. The Gunpowder Plot has been celebrated ever since with the ceremonial burning of an effigy of Guy Fawkes, attended with fireworks, on Bonfire Night on the 5th November each year. The rhyme “Remember remember the fifth of November, gunpowder treason and plot. I see no reason why gunpowder and treason shall ever be forgot” is still chanted by children to this day.

King James’ important place in history was confirmed not by a failed assassination plot but for something far more worthwhile, that of him being the sponsor of the Authorised Version of the English Bible, the publication of which in 1611, would be his lasting legacy to the world. The spreading of God’s word in the vernacular by way of the “King James Bible” was the start of the English tongue becoming the global Lingua Franca it has become.

Title page of the King James Bible

To understand fully the story of the “King James Bible” we have to go back in time to earlier translations which were deemed to be seditious and heretical by the Roman Catholic Church. In Medieval Europe the orthodox view was that to make the Bible accessible to common folk would threaten the authority of the Church and lead people to question its teachings. A Yorkshireman, John Wycliffe (1330-1384) educated at Oxford, was the first to translate the scriptures and was denounced as a heretic for doing so. He had many followers, who called themselves “Lollards” and they in turn were persecuted by the “Powers that be”.

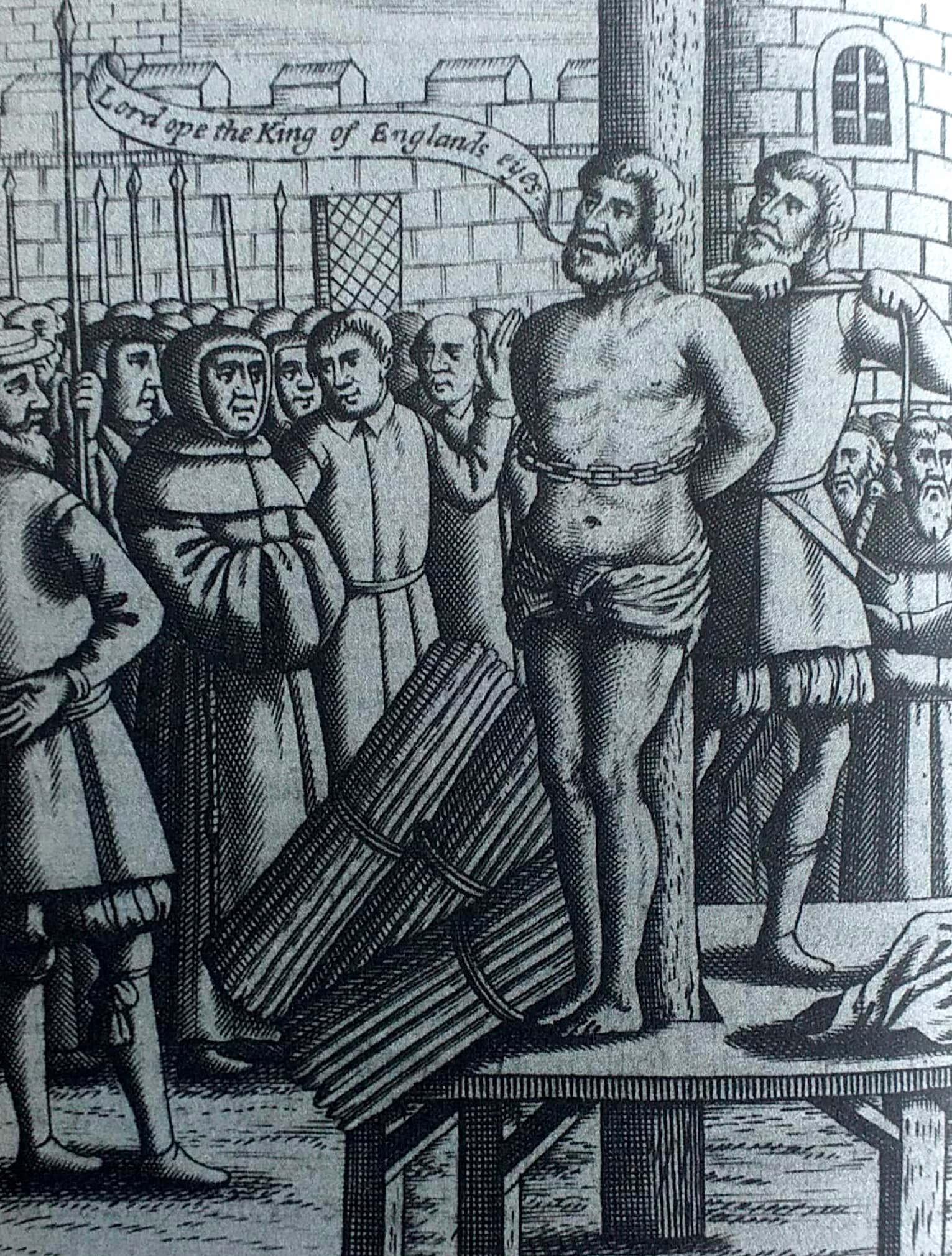

William Tyndale (1494-1536) would be the next to translate the New Testament (from the Greek) in 1525 and it is said his prose was written for the Ploughboy, thus easy to comprehend. Like Wycliffe he was vilified by Church and State and was forced to flee to the continent, where he completed his translation in hiding from the agents of Henry VIII. He was able to print and surreptitiously send copies back to England where he had a large following. He however was racing against time to translate the Old Testament when he was arrested in Flanders in 1534, imprisoned and put to death in 1536.

Death of William Tyndale

Ironically the English Reformation reached a turning point in 1534 when Henry VIII (“Fid. Def.” - Defender of the Faith) cynically broke with Rome, as Pope Clement VII would not countenance his divorce from Catherine of Aragon (the Pope at the time was a virtual prisoner of Catherine’s nephew, Emperor Charles V). Henry would not be denied and he would divorce his Queen in order to marry another – Anne Boleyn (mother of the future Queen Elizabeth I).

In 1535 Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), a disciple of Tyndale, published in Zurich the first complete version of the Bible in English, which began a flurry of further translations; Tavener’s, Cranmer’s (the “Great Bible”), the Geneva and then the Bishop’s Bible. The latter two were the cause of the argument between Puritan (Low Church) and Anglican (High Church) the Geneva version with copious marginal notes was espoused by Puritans and the Bishops Bible was to be found in all Anglican churches.

The “King James Bible” was written to satisfy both parties, however on publication it was not an immediate success and it would not be until the end of the English Civil War (1642-1649) that it was universally accepted, especially in the newly founded colonies of America.

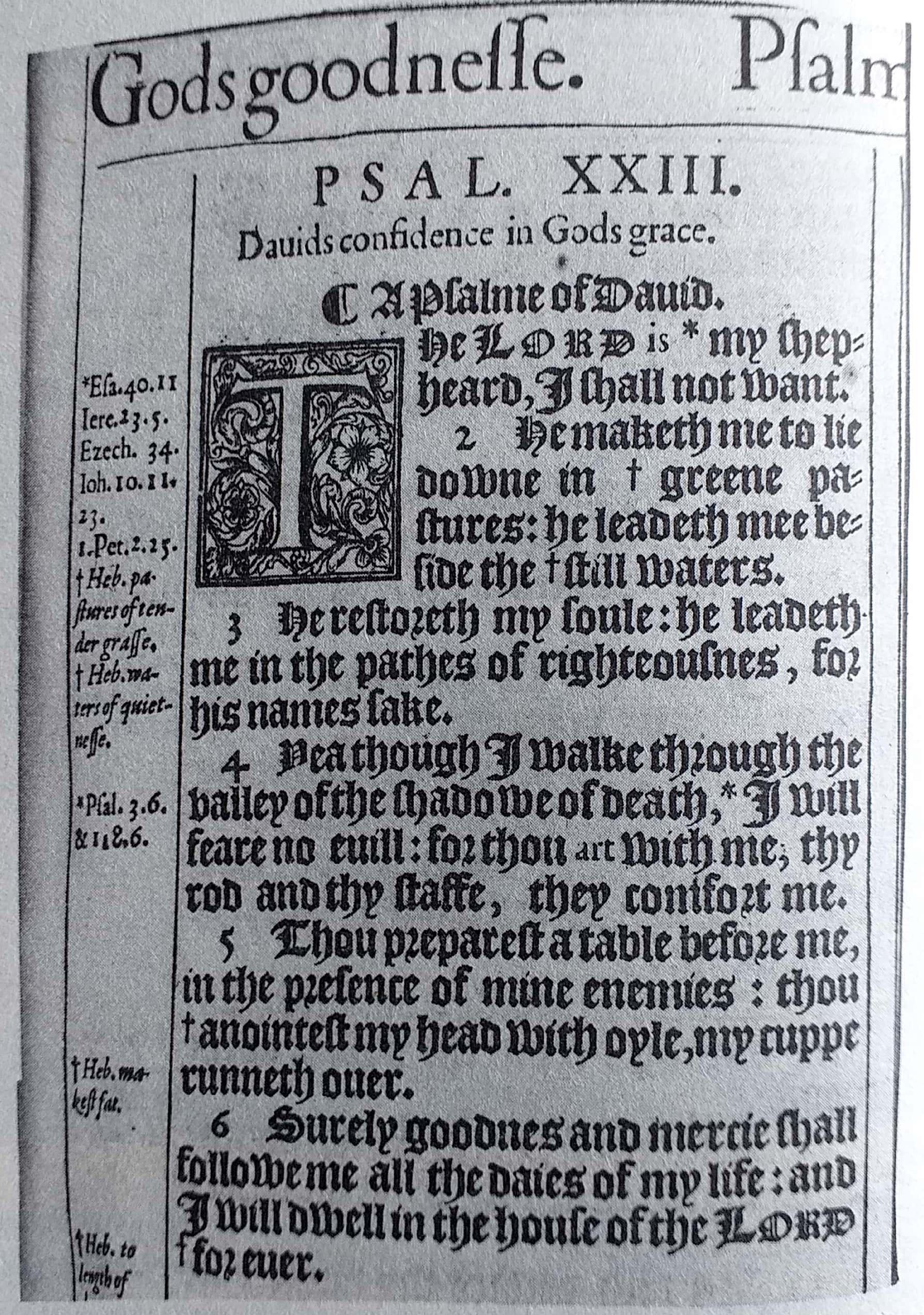

The “King James” was written more for the ear than the eye, as most people were illiterate at the time of its printing (1611) and it was expected that its chapters and verses would be preached from the pulpit. That its translation was achieved by a committee and not by one man is a tribute to those entrusted with the scholarship that took six years of diligent research. The translation from Greek and Hebrew texts was shared between six “Companies” (groups), two each from London, Oxford and Cambridge; with nine scholars per group. It was a mammoth task made a little easier by reference to William Tyndale’s erstwhile version and it is no idle statement to make that he was the real Father of the English Bible.

Psalm 23 in the King James Bible

The “King James” version has sold in the billions of copies over the last 400 years notwithstanding the printing of the Bible in modern day language since the 1960s, it would seem that we prefer its archaic but poetic narrative as being the true word of God. Succinctly stated on a bumper sticker “If it ain’t the King James it ain’t the Bible”.

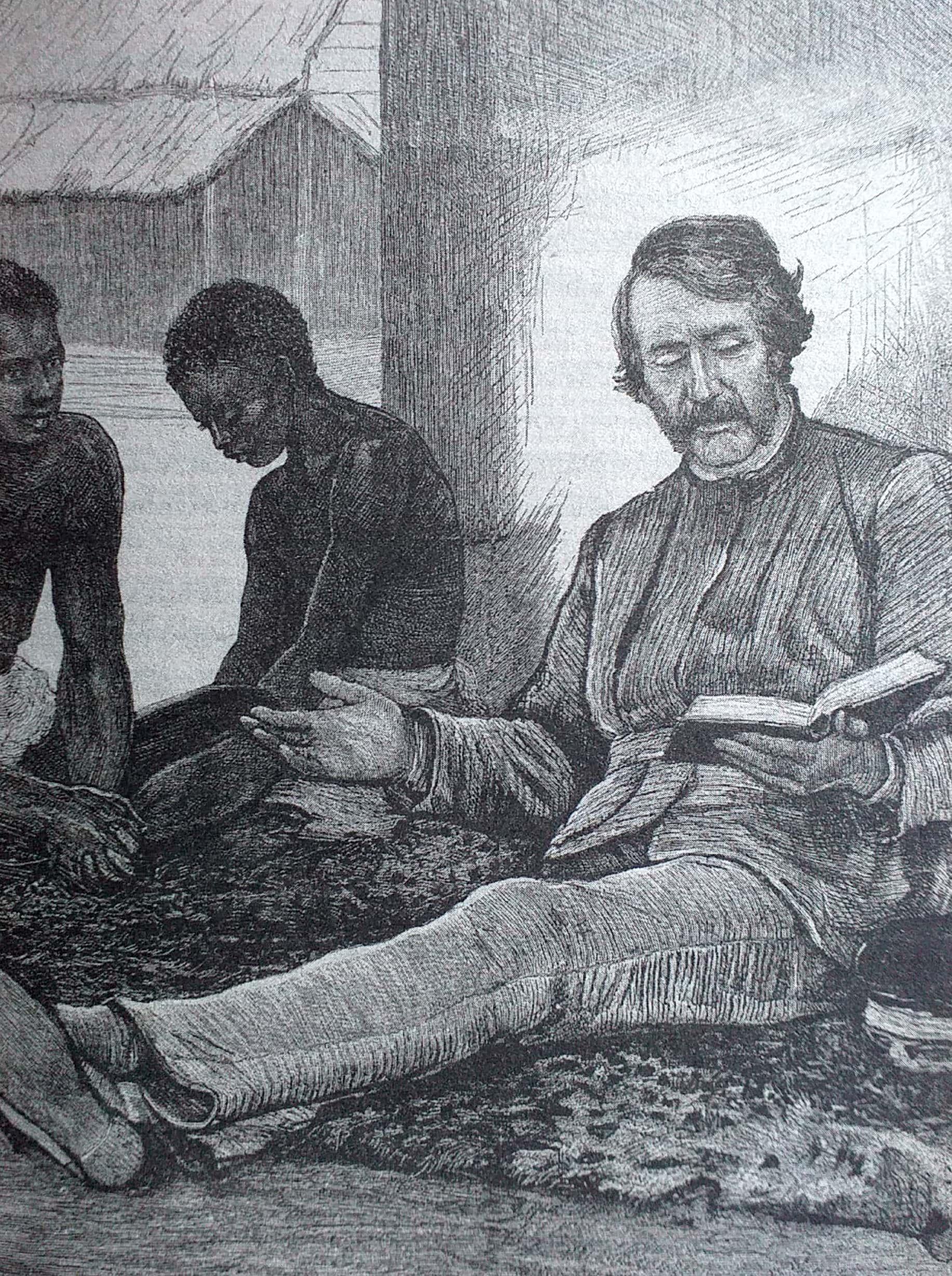

David Livingstone reading the King James Bible

For more detailed information on the “KJB” I implore the reader to go onto YouTube and search “The King James Bible”, there are four really good documentaries roughly an hour long but they are well worth watching.

References and further reading:

- “The Book of Books - the Radical Impact of the King James Bible 1611-2011” by Melvyn Bragg, published by Hodder & Stroughton, 2011.

- “12 Books that Changed the World” by Melvyn Bragg, published by Hodder & Stroughton, 2006.

- “The Story of English” by Robert McCrum, William Cran & Robert MacNeil, BBC Publications, 1987.

- “The King James BIBLE, Making a Mastrpiece” by Adam Nicolson, National Geographic, December 2011.

- “Our Language” by Simeon Potter, first published in 1950, revised in 1966 & reprinted by Penguin 1990.

- “Mother Tongue – English & how it got that way” by Bill Bryson, published by Avon Books, 1990.

- “Dictionary of British History” by J P Kenyon, published by Sphere Books Ltd. 1988.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.