Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

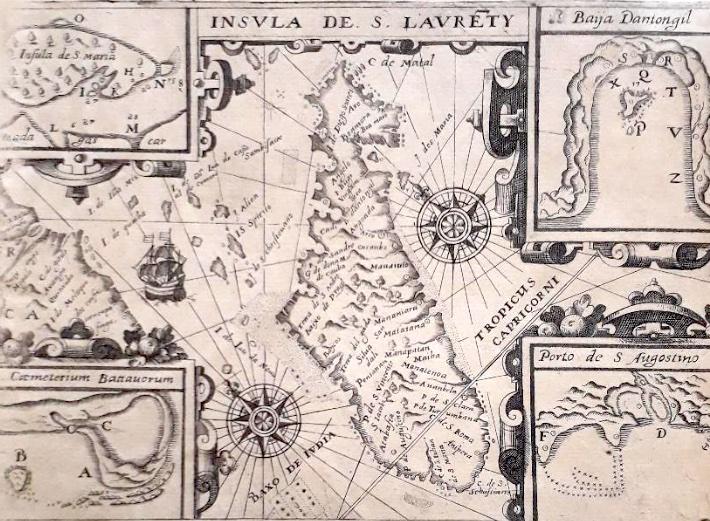

On first inspection, this small map (20 x 14 cm) is unimpressive and would seem to be of little heritage interest to South Africa. But why the four small insets in the corners? Once I had confirmed the source of the map, I started to delve into the stories it revealed.

The map

The title of the map is in Latin (Insula de S Lauenty, i.e., the Island of St. Lawrence) as is the page headline Insula Madagascar alias S. Laurentii Dicta, & huius conditio (The island of Madagascar, otherwise called St. Lawrence, and its condition). Despite the Latin title, many of the place names are in Portuguese.

Not unexpectedly, the small chart includes a ship sailing through the Mozambique Channel, two compass roses from which rhumb lines (compass bearings) emerge.

There are tiny inset maps in each corner of the map boundary: Insula de S. Maria (Island of Saint Mary); Baija Antongil (Antongil Bay); Porto de S. Augostine (The port of Saint Augustine) and Caemetrium Battavorum (Dutch Cemetery).

The text below the map is also in Latin and provides the key to the letters on the insets.

‘Madagascar is drawn here, with its sands and rocky cliffs: “A” is the place where we first anchored, “B” Is the island where many of the sailors were buried in the Dutch Cemetery, “C” a fresh-water lake, “D” a stream of fresh-water, “E” the Dutch trench, “F” the corner of the port of St August, “G” A small island to the south, “H” The island of Santa Maria, “I” A convenient cove of Santa Maria, “K” The most important village of the island, “L” & “M” The two arms of the river, “N” A rock on the west side of the Island, “P” A small island in the cove for fresh water, “Q”, A stream, “R”, The village of St Angela, “S” The village of Spakenburg, “T” The village in the north, “V” The village where we first maneuvered, “X” Where we first anchored, “Y” & “Z” Two other villages.’

The full map Insula de S Lauenty

The map was published first in the 1599 German edition of Petit Voyages, written by Theodore de Bry, who orientated the map with northeast, not north, on top. This example of the map appeared in 1601, in the first Latin edition of the book. It illustrated the story of the first Ducth voyage to the East Indies (April 1595 to August 1597). The map was engraved by De Bry himself (he was an acknowledged goldsmith and engraver) but clearly it is derived from the map by Petrus Placinus (see below).

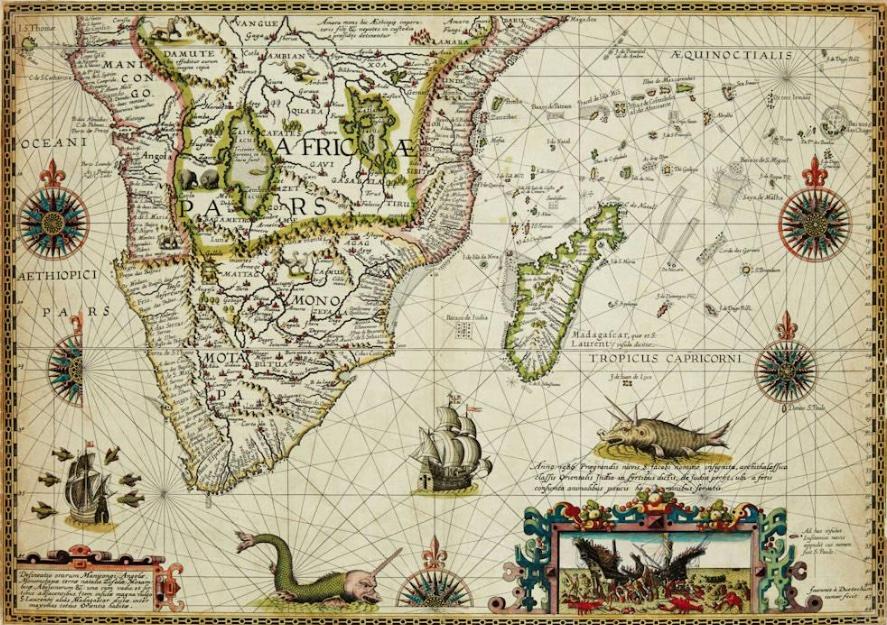

Madagascar cropped from the 1592 Plancius map of southern Africa.

The Story

Peter Flatfoot

A convenient start to the story is Peter Flatfoot (Pieter Platevoet, who preferred to be called Petrus Plancius, his Latin name). He was a Flemish minister of the Dutch Reformed church who wisely fled to Amsterdam in 1585 to avoid the Inquisition when catholic Spain conquered what we now know as Belgium.

He became interested in cartography and navigation and studied Portuguese charts that had reached Amsterdam, some by trade and some by theft. Plancius said he had obtained the maps he studied from Spain's royal cosmographer, Bartolomeo de Lasso. In 1592 Plancius produced a world map that showed the route to the East Indies. He also produced a beautiful map of southern Africa that included Madagascar – only four copies have survived. This map had a long title: Delineatio Orarum Manicongi, Angolae, Monomotapae, Terrae Natalis, Zofalae, Mozambicae, Abyssinorum &c. Una Cum Vadis, et Sirtibus Adjacentibus. Item Insulae Magna Vulgo S. Laurentii Alias Madagascar Dictae, Inter Maximas Totius Orientis Habitae. (Depiction of the coastal strips of Manicongo, Angola, Monomotapa, Natal, Zofala, Mozambique, the Abyssinians etc., together with the shallows and sandbanks along them. And also of the big island that is usually called Saint Lawrence or Madagascar that is counted among the very largest islands of the entire Orient).

Plancius’s map of southern Africa, 1592 (Swann Galeries)

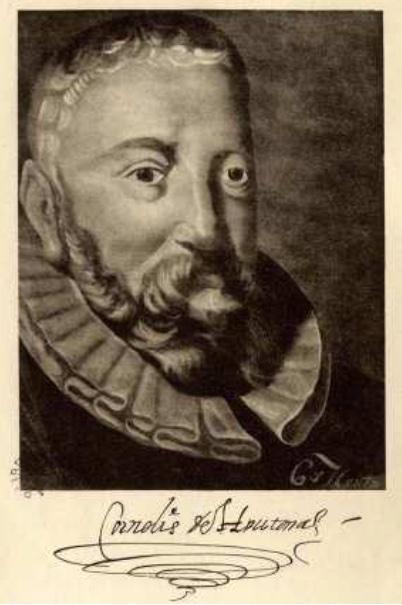

Dutch merchants were keen to enter the spice trade in the East Indies which had been dominated by the Portuguese since the late fifteenth century. So, in 1592, they sent Cornelis de Houtman and his younger brother Frederick to Lisbon to verify the Plancius maps and obtain further information. It is not clear if this goal was part of legitimate business or commercial espionage. The latter is likely because the Portuguese imprisoned the brothers for attempting to steal secret charts of East Indian sailing routes.

Cornelis de Houtman

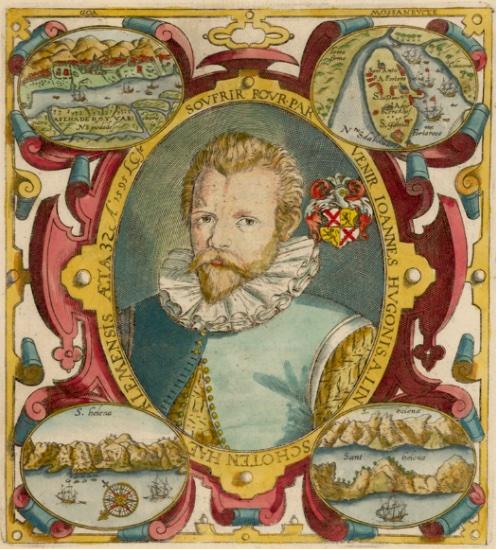

Linschoten

Later that year, Jan Huygen van Linschoten, returned to Amsterdam after having spent almost nine years in Portuguese occupied Goa, on the west coast of India. He had been the Portuguese archbishop’s secretary but was also a spy. He travelled extensively in the East Indies where the Portuguese had influence. He carefully copied Portuguese charts and detailed navigation information. He published all this important nautical and trade information in 1596 in his Itinerario (Navigatio ac itinerarium Johannis Hugonis Linscotani in orientalem sive lusitanorum Indiam).

Jan Huygen van Linschoten

Dutch Voyage

The Dutch merchants absorbed this plethora of information and formed a company, Compagnie van Verre (Landen) and raised capital. They constructed three warships for a voyage to the East Indies (Mauritius, Amsterdam, Hollandia) and a small sailing boat (Duifje) was included in the fleet. The primary purpose of the voyage was to established trade in spices. Cornelis de Houtman was in command and Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser, who had been trained by Plancius, was the chief pilot on the Hollandia.

An illustration of the fleet in De Houtnan’s journal

- April 2, 1595 - Texel – The fleet sets sail to the East Indies.

- April 26, 1595 - Canary Islands - Passage through the Canary Islands

- August 4, 1595 - Arrival in Mossel Bay

- August 8, 1595 - The crew goes ashore to get oysters and mussels

- August 11, 1595 - Mossel Bay, South Africa - Houtman resumes voyage.

- September 3, 1595 - Arrival in southern Madagascar.

- September 13, 1595 - Island of Nosy Manitse, off southwestern coast.

- October 9, 1595 - St Augustin Bay, southwest coast of Madagascar

- December 14, 1595 – depart St Augustin Bay.

- January 5, 1596 – Arrival at ST. Mary's Island, northeast Madagascar - On the way to Java they are forced by a storm to return to Antongil Bay

- February 12, 1596 - Saint-Mary's Island, NE Madagascar - resume voyage to Java.

- August 14, 1597 - Texel - Return of the first expedition

Mossel Bay

The expedition saw and rounded the Cape of Good Hope but landed at Mossel Bay (kown as De Baij van San Bras). They bartered with the local Khoi, exchanging sheep and cattle for pieces of iron – but no fruit and vegetables for treatment for about half the crew, who were suffering from scurvy. They then continued their voyage, with Madagascar the next destination, in the hope of finding fresh fruit and vegetables.

Madagascar

Diogo Dias was the first European to discover Madagascar, 10 August 1500, after his ship separated during a storm from the 2nd Portuguese India Armada which was travelling to India. The Portuguese traded with the islanders and named the island São Lourenço (after the festival day of the martyr, Saint Lawrence).

Diogo Dias's Ship

When De Houtman sighted Madagascar in September 1596, seventy-one members of fleet had died, most from scurvy. They set anchor off a tiny island where they buried many of the dead. Consequently, they named the island Dutch Cemetery (Caemeterium Battavorum on the map); it is now known as Nosy Manitse. Among the dead was the skipper of the Hollandia, Jan Dignumsz. His death set off one of numerous feuds that beset the entire voyage. Pieter Keyser, assisted by Cornelis de Houtman, made astronomical observations on Madagascar.

They proceeded further north along the coast of Madagascar to St. Augustine’s Bay where they traded with the locals and possibly derived some relief from scurvy. In December 1596, they then headed to St. Mary’s Island a short distance off the northeast coast of Madagascar. In January they departed the island and headed northeast for Java but were forced back to the nearby St. Antongil Bay for protection from a severe storm. They remained there for another month while they stocked up on provisions.

Java and return

The fleet then set off for Java where they had a tempestuous sojourn. Probably due to poor leadership they fought with the locals and ended up having to set the severely damaged Amsterdam on fire and scuttle it. Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser, the pilot died on the voyage in the east – the record of his observations was delivered to Plancius who created a celestial globe and sky chart. The remaining ships then went to Bali and set off for home on February 26, 1597.

They reached Texel on August 14 of the same year. Only eighty-nine of the 249 members of the fleet survived the entire voyage! Their haul of spices was much less than expected but sufficient for the merchants to make a small profit.

Epilogue

Although the first Dutch voyage was anything but a commercial and diplomatic success, it was the beginning of Portuguese decline and Dutch ascendancy in the spice trade. In 1602, the Compagnie van Verre merged with other companies to form the United Dutch East India Company (VOC), the first public company, which, in 1652, led to the settlement of the Dutch on the shore of Table Bay.

On a second voyage (1598–99), the De Houtmans established trade with Madagascar. They returned to Sumatra, where Cornelis was killed in a battle. Frederik de Houtman, who was imprisoned in Sumatra, studied the Malay language and returned to Amsterdam where he wrote the first Malay dictionary. He later served as governor of Ambon and the Moluccas, now part of Indonesia.

VOC trade in Madagascar included slaves (click here to read more). Some decades later, Pieter van Meerhoff, a VOC soldier, visited Madagascar. He had been on journeys through Namaqualand to the north of Cape Town and was the husband of Eva Krotoa – the first legal mixed-race marriage in the settlement. In 1668, he was on board the VOC’s Westwout that went to Antongil Bay on a slave trading expedition. He did not return. On the 27th of February of that year, he and eight other crew members died during a skirmish with the locals.

“That's the thing about old maps. They let you travel in space and time without moving your feet.” (Apologies to Jhumpe Lahiri, The Namesake, New York, 2003)

Roger practiced medicine, was associate professor of human physiology, and has been an executive and director of businesses locally and abroad. He has also collected historical maps of South Africa and the continent of Africa; these maps are now conserved at the University of South Africa and Stanford University, USA. His articles on the maps and Cape history have been published in international journals and local periodicals.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.