Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below Cathy Robertson tells the story of the meticulous restoration of Onze Molen in Durbanville in the mid 1980s. The article was first published in the 1986 edition of Restorica, the journal of the Simon van der Stel Foundation (today the Heritage Association of South Africa). Thank you to the University of Pretoria (copyright holders) for giving us permission to publish.

One normally associates the romantic vision of windmills, with their sails turning majestically in the wind, with Holland. A portion of the Cadastral map of Cape Town c.1893 indicates that this was a common sight along the Liesbeek and Black valleys too. The most familiar windmills were the truncated-cone tower-mills which were in evidence early in the eighteenth century. Only one South African windmill with wings has survived the ravages of time - Mostert's Mill in Mowbray. It was restored in 1935 by a famous Dutch millwright, Bremer. He left a maintenance manual for adjusting and repairing the mill and this is preserved at the mill.

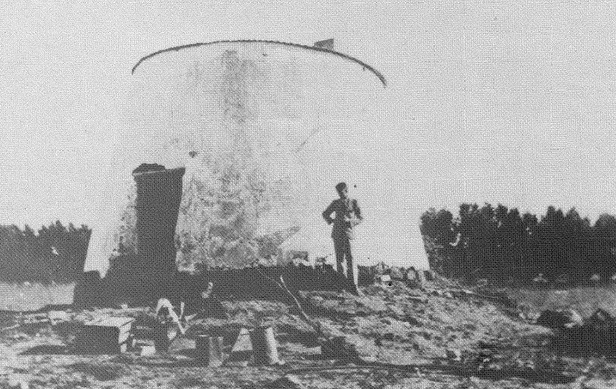

There were many watermills and horsemills in the country areas but very few windmills. A few simple tower-mills were erected in the Western Province. The tower of one still stands at Windmeul, Agter-Paarl, the base of another in the district of Malmesbury and a portion of a tower at Durbanville was used as a basis for the reconstruction of Onze Molen.

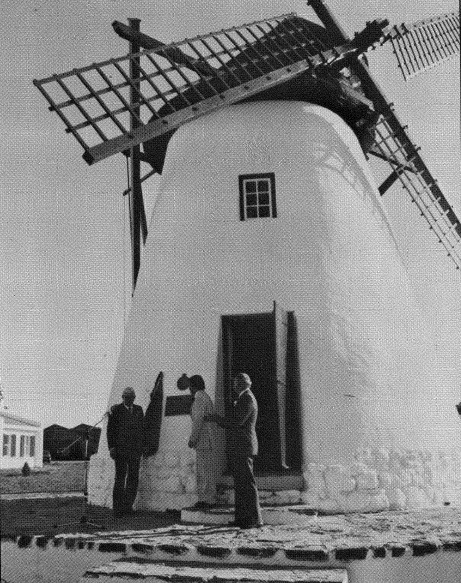

This windmill at Durbanville has been reconstructed as the focal point of a building project financed by the Natal Building Society, making it the second completed Cape windmill to have survived the past.

Opening of Onze Molen

Originally Johannesfontein, Onze Molen was the name of the farm on which the Durbanville remnant stood. The previous owner never saw it operating as a windmill, but he remembers it as a horse-mill. According to James Walton's Watermills Windmills and Horse-mills of South Africa, it is remembered as having had sails earlier this century by a number of the older residents. The original windmill was most probably constructed during the 1840s.

As there is no known millwright in South Africa, the reconstruction of Onze Molen windmill had to be undertaken by someone who would have to rely on personal research, intuition and sensitivity. Paul Woolley is that sort of person.

British by birth, Paul attended school at Rondebosch Boys' High School in Cape Town where he matriculated in 1970. Woodwork was one of his subjects. At school, he had always been a loner and spent a great deal of his time meditating.

This quest for spiritual fulfilment resulted in his entering a Ramakrishna ashram in Durban where he spent ten years. He returned to Cape Town in 1981 where he worked as an artisan for a property building and maintenance company. He decided to concentrate his skills on carpentry as he has always loved creating something with his hands. His talent was discovered by Len Raymond, Director of Daljosaphat Restorations, when Paul assisted him with the restoration work of the Zion Church in Paarl. He was Mr Raymond's obvious choice of craftsman for the restoration of Onze Molen.

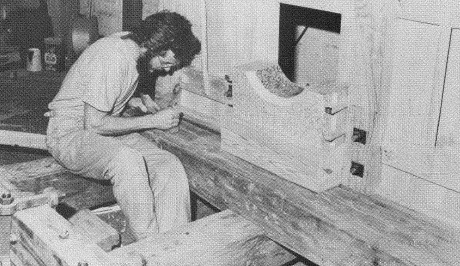

Paul Woolley at work

Paul's ability to meditate and reflect, and the rigid discipline he experienced in the ashram, have influenced his approach to his work. The only information accompanying his brief was Bremer's maintenance manual for Mostert's Mill. Unable to understand Dutch, he studied the illustrations in Anton Sipman's Molenbouw and lr. F. Stokhuyzen's Molens to absorb the essence of Dutch windmill construction, the predecessor of the first South African windmills. Paul tried to imagine how it had felt to be a millwright in early times as he wished to re-create the windmill of the past as authentically as possible. James Walton's book was also a valuable source of information.

Mostert's Mill was his real inspiration and provided most of the construction details for Onze Molen. All that remained of Onze Molen was a four-meter high trunk with a corrugated iron roof. This construction had provided adequate shelter for labourers on the farm. The height of the reconstructed trunk had to be determined by the existing base. It is higher than Mostert's Mill and narrower at its peak.

The wooden mechanism of the cap was carefully made in the workshop of Daljosaphat Restorations in Paarl. It was then dismantled, transported to Durbanville and re-constructed on site. As thatching the cap would have been difficult once it had been placed in position on the tall trunk, the cap was thatched on the ground and the entire structure was then hoisted by crane onto the trunk.

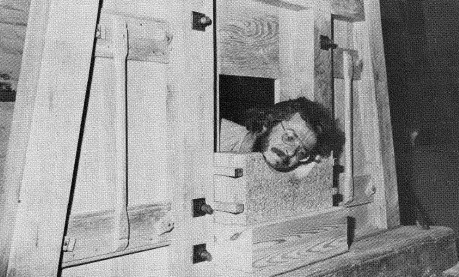

The framework of the cap rests on a circular wooden wall plate. The wind turns the sails which turn the drive shaft resting on a granite block resembling the block on which French Revolution victims rested their necks before being guillotined. The drive shaft turns the enormous wooden hand-crafted gear which is 1.5 metres in diameter. This gear activates another gear which sets the verticle drive shaft in motion. The vertical shaft operates the enormous millstones. Most South African mills only had a single pair of millstones.

Paul Woolley resting his head on the drive shaft block

The mechanism has a semi-circular Rhodesian teak brake, carved out of an old wine storage vat. The red of this wood contrasts warmly with the yellow glow of the American oak gear. A chain, which hangs onto the ground outside the mill, where it is secured to a pole, is connected to the end of the brake lever in the cap. This brake lever is a heavy wooden bar which is pivoted on one end and weighted on the other by a box filled with heavy stones. Paul has made this box beautifully, using old wood joined together with dovetail joints. When the chain is pulled the brake is released. It moves against the brake wheel, stopping the gear from turning. Millers had to be careful about applying the brake too suddenly in a strong wind. The wings were in danger of flying off or the pressure of the wooden brake shoe could generate enough heat to cause a fire. So the miller had to watch the weather constantly as bad weather could cause the windmill's destruction. When the mill was not in operation, the sails were removed and the wings secured.

The cap can be rotated on its base to face into the wind. As the wind at Durbanville comes mainly from the South East, Paul felt that the wings should face the wind. However, this would mean that the residents of the housing scheme around the mill would look onto the back of the mill. It was therefore decided to face the wings North West, crossing over the door which gives access to the tower. This position of the wings in millers' language means that the mill is not operating. Usually the wings were left in a perpendicular position, but to prevent anyone from climbing the wings, they could be left in a diagonal position. In this case, the stones had to be secured to act as an extra brake.

The essence of the past has been recaptured by the lofty elegance of the second windmill with wings in South Africa -a remarkable and worthy achievement for the developers, the Natal Building Society, and for Paul Woolley, South Africa's millwright of today.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.