Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This article "Slave Sales and Cape Town's Slave Tree Memorial" by Jaqueline Lalou Meltzer was previously published in the Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa volume 73, number 1 (June 2019): 17-36 and is reprinted with the permission of the Editor of the Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa. Click here to download the original article containing footnotes.

A quaint custom was observed in the Cape in the old days by the less inhibited citizens. They used to “bury the old year” a few minutes before midnight and immediately afterwards they greeted the New Year with shouts of: “The year is dead – long live the year!” That was in the days when New Year revellers of Cape Town belonged mainly to sporting clubs, and the Afrikaans name for them was klopse (clubs). The ceremony was preceded by festive marches to the yew [sic] tree that used to stand on Church Square. There they gave the old year, with all its disappointments, its fears and its sorrows, a symbolical burial, and one old writer describing the event in 1888 said that their torchlight processions with “impromptu bands innumerable” added “to the grandeur of the rites of the dead year.” Cape Times - 29 December 1979

Located on the traffic island in Spin Street in Cape Town is a memorial inscription which, built into the paving, is now almost illegible owing to the heavy flow of pedestrian traffic. It is just possible to make out the apartheid-style bilingual English and Afrikaans inscription, installed in 1953, as follows: "Op hierdie plek het die ou slaveboom gestaan | On this spot stood the old slave tree.

Slave Tree memorial on the traffic island in Spin Street (Jaqueline Lalou Meltzer)

The slave tree site has never been accorded national heritage status, either by the old National Monuments Council or by its post-1994 successor, the South African Heritage Resources Agency. It remains today a somewhat neglected memorialisation taken up in the course of its existence by the Cape Town Municipality. But the slave tree site has been kept alive as a site of slavery and oppression in the minds of people of slave descent. The Rev. Michael Weeder, today the Dean of St. George’s Cathedral, said, as he stood at the site of the slave tree in 1996:

What does this tell you about what happened here? Families were destroyed here. Children sold to one person, their mothers sold to another. A woman sold to a farmer in Stellenbosch, her man sold to a merchant in Cape Town. Can you imagine that? Can you just imagine what it was like, all the misery that happened here on the ground beneath our feet.

Weeder then told of a childhood memory: his mother would always say a prayer when she passed near this spot. When he asked her why she did this, he was told that bad things had happened there to our people. He added: “This doesn’t acknowledge what was done to our people,” he said, placing his foot on the memorial. “There is no sense of spirit here, no sense of the past. This is not a place where you can reflect on the suffering of those people. If you can’t see the country’s past, if you can’t hear the voices from the past, then you can’t understand the present.” It is time we bring historical research into a relationship with such strongly felt oratory in order to explore the memorial’s meaning and history and the extent of myth making in the course of memorialisation.

Trees and Sales of Enslaved People

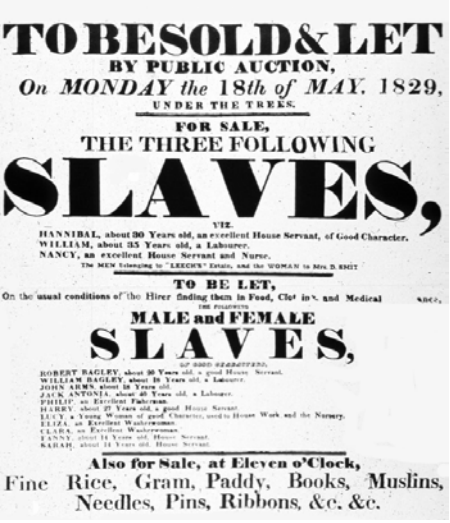

In the USA trees are sites of memory of racial lynching. Trees in Zambia and Ghana are memorialised as having connections to the selling of enslaved people, while slave sales took place “under the trees” on British St. Helena, according to an advertisement dated 1829.

St Helena slave sale advert (poster), 1829 (Slavery Images)

While there is a strong popular link between the sale of enslaved people beneath a tree in Spin Street/Church Square, no conclusive historical evidence has been found until now. The only visual representation of slaves being sold at the Cape (accompanied by the traumatic break up of the families) is an engraving done towards the end of the formal days of slavery which appeared in a British periodical in 1832 to promote the cause of abolition.

“Sale of a Negro family at the Cape of Good Hope, 1824” (NLSA - Cape Town Campus)

Within the first fifty years of colonization Cape society had become slave based, with the majority of the population enslaved. The bulk of the many thousand slaves was the private property of European colonists. After land and buildings, enslaved people were the most valuable form of wealth. Property auctions on farms in the rural areas were a common feature of colonial life from the early times of the VOC (Dutch East India Company) and have been described in first-hand accounts by the colonists and documented by contemporary historians of colonial social life. Trees provided a handy reference point for outdoor sales and in summer offered shade for buyers, not relief for the human, objectified form of property. Enslaved people were elevated for inspection, as Lady Anne Barnard remarked during the First British Occupation and M. D. Teenstra in 1825. Most sales in and around town were conducted at the home of the dead person during VOC times.

Numbers of Asian slaves were transported to the Cape for sale by VOC officials, crew and passengers returning from the East en route to the Netherlands. Each person was permitted limited numbers of slaves but there were many clandestine enslaved people on board intended for sale for personal gain. Agents operating between the Cape and Batavia frequently set up sales of slaves in advance of the ships’ arrival at the Cape. Illegally enslaved people were probably sold on board or at private homes rather than in public spaces. Over the period of VOC rule many proclamations were issued forbidding or restricting such transactions but the Company yielded in time to financial pressures and the limited availability of Company ships, and towards the end of 1792, it granted conditional free trade to the colonists, which included permission to trade in slaves. At the same time an import duty of 10 rixdollars was implemented to improve the finances of the colony.

The VOC authorities at the Cape also sent ships on slaving voyages to different parts of east Africa, primarily Madagascar and Mozambique. The voyages, conducted by officials the like of François Renier Duminy, were to capture men, women and children for government labour, to be confined in the Slave Lodge. On their return officials and crew of the slaving ships likewise sold enslaved people at great profit, probably partly clandestinely. Sales probably took place aboard ship after docking in Table Bay or at the official’s home on a small informal sale—unless perhaps there was authorisation to sell slaves by public auction conducted by the Company’s vendumeester at their home or store. There is little reason to expect such sales to have been conducted overtly in public places such as in Church Square unless the slaveowners and traders lived there (Duminy and his brother-in-law François de Lettre for instance lived in Church Square) and the slaves were legally acquired. Slave traders and agents may have sold slaves outside their stores and houses as was done in town in the early years of the 1800s but no evidence of this has been found for the VOC period.

Enslaved people in large groups and at increasing intervals in the later eighteenth-century were brought to the Cape for private sale by foreign national slaving ships sailing to the plantations of south America and the Caribbean, with French ships increasing in the last decades of the eighteenth-century. In 1782 the VOC allowed the captain of the Sainte Anne on the way from Mozambique to Saint Dominique (later the independent black republic of Haiti) to sell, by public auction, numbers of many poor and emaciated slaves. Again one can only guess where such sales were conducted: perhaps on board, or at the Castle or prison built near the shore during the later eighteenth-century. On an earlier occasion a French sea captain had in 1773 asked that his ship La Digue sailing to Martinique be allowed to land a large group of slaves from Mozambique to recuperate. He was granted permission by the Cape administrators as long as the enslaved people were lodged in one of the most remote houses in Table Valley. Again in 1791 enslaved people from three French ships were landed for recuperation on condition they were housed at outlying and outermost houses and they were not walked in central town where they could give offence to decent citizens because of their visible sickness and nakedness! The early newspapers of the 1800s give abundant examples of sales of enslaved people brought to the Cape by French and Portuguese ships as well as their sale in gardens around town and at stores in and around the centre of Cape Town. It is possible that sales such as these had begun to take place in town stores and gardens during the last decades of the VOC.

VOC policies on many issues began to be reversed in the course of the last decades of the eighteenth-century as the Company went into financial decline. Karel Schoeman points out that in the 1780s and 1790s the Cape authorities had begun to buy slaves for resale to the colonists and in this way was also able to supply its own wants. A logical place for the sales of these slaves would have been the nearest open space in front of the Slave Lodge. At that time, the front of the Slave Lodge faced on to Church Square, while the back overlooked the Heerengracht, later re-named Adderley Street. Furthermore, during the last years of its existence the VOC at the Cape began to sell its own slaves from its outlying posts and in 1791 the Company reported the sale of some of the enslaved people at the Lodge. Perhaps these Lodge sales also took place in Church Square.

Insolvency and Church Square

In 1803 the Dutch Commissioner-General J.A. de Mist, sent by the Batavian Republic to take charge of the Cape after the first British Occupation, passed South Africa’s first insolvency legislation among a number of other financial and social reforms, which did not include the abolition of slavery. Civic debt and insolvency had led to years of backlog accumulated by the Secretary of the Cape’s Court of Justice who acted also as Sequestrator. De Mist established a Desolate Boedelkamer (Abandoned/Unmanaged Estates Chamber) and in August 1803 one of the earliest mentions of the work of the Desolate Boedelkamer in Cape Town to settle issues of sequestration, insolvency and civil debt appeared in the press. This sale, which included the auction of slaves, took place at the house of the Hermanus Keeve, “exploicteur.” It set the pattern for the ensuing years of the Desolate Boedelkamer’s existence, and the decades beyond, with sales of fixed property (connected with enslaved people and moveable property), taking place in the country areas and towns at the house of the insolvent. Sales of only moveable property (including slave people) took place in country areas at various places including public offices; and sales of moveable property (including slaves) in Cape Town took place at the house of ‘exploicteur’. Throughout the duration of the Batavian Republic sales by the Desolate Boedelkamer of moveable property and slaves in Cape Town were conducted at the home of Hermanus Keeve at 17 Castle Street. After the Second British Occupation in 1806, they continued at his house, but under the authority of the renamed Chamber for Regulating Insolvent Estates (CRIE). Keeve, later referred to as Messenger of the Chamber, was replaced in 1815 by auctioneer John Blore of Plein, Long and Roeland Streets. As an example of the sales, the following people were sold on Saturday 26 July 1817 for the account of Jan Diederik and Nicolaas Johannes Vos:

Africa of the Cape, coachman; April of Mosambique, houseboy; Dollie of the Cape, houseboy; Mannon of Batavia, house and child maid, with her children Manna of the Cape (13 years) and April (10 years).

On Saturday 2 August 1817,

Frans of the Cape; Symon from Mosambique, a cook; Manuel from Mosambique, billiard marker; Doortje of the Cape; Caroline of the Cape; and Doortje from Mosambique

...were sold to settle James Dick’s debt. The numbers of enslaved people sold at such premises around the city centre steadily increased. In 1817 some 77 enslaved people were sold to settle slave-owners’ debts.

In December 1818 the Government dissolved the CRIE, replacing it with the Sequestrator’s Department. In late 1819/early 1820 the Sequestrator appointed auctioneer H. A. Smit whose premises were at 15 Grave [Parliament] Street in the vicinity of Church Square. Smit’s premises served until early 1826. All in all, a couple of hundred slave people were sold in the houses and stores of the Exploicteur, Messenger and Auctioneer between 1803 and 1826.

Other developments at this time help to flesh out the story of Church Square and slavery. The first is the sale of prize slaves advertised throughout the period. For instance, in October 1800 the Vice Admiralty Court decreed the sale of 34 male slaves at the storehouse of the Widow Oosterzee at the corner of Zieke and Lange Mark Streets. These slaves had been part of the prize cargo of Le Glaneur, captured by a squadron of the Royal Navy. And in 1806 the prize sale of “200 very fine male and female slaves” took place in the garden of Josias Brink. The sales of slave people in the open, often in large groups, became an increasingly common sight in and around Cape Town during the first decades of the nineteenth-century. On 14 April 1804 Paulsen de Oude advertised the sale of male and female slaves “in ’t openbaar” in Loop Street and in 1823 merchant William Robertson in Church Square advertised fabric sales which, should the weather be unfavourable, were to be held indoors. A slave selling connection with Church Square had begun to emerge. The merchant and later French consul, François de Lettre, who earlier had been part of the slave expeditions captained by François Duminy (his brother in law) lived in Church Square. In January 1803, by example, De Lettre advertised 20 slaves for sale and in July 1803 sales inter alia of sugar, toilet mirrors and six male slaves, to take place at his Church Square premises, an address which he later describes as being at the corner of Church Square.

On 19 May 1826 the Sequestrator’s Department announced a sale of moveable property (including Philida, a female slave, on account of Jan Daniel de Villiers) at his new store in Church Square adjoining the residence of Dr Van Oosterzee, at the corner of Spin Street. In the early 1800s De Lettre is listed at no. 2 Church Square, described as being on the corner of Church Square, viz. the corner with Spin Street. The street numbering of the Square at the time ran from the corner down towards the sea and then around the bottom end of the Square. No. 1 Church Square had by 1815 become the premises of the above mentioned merchant William Robertson and then later the home and store (in separate or conjoined buildings) of Dr Van Oosterzee. His store, located at or very near to the corner of Church Square and Spin Street, was taken over by the Sequestrator and from there slaves were bought and sold between 1826 and 1834/5 to settle sequestration and insolvency debt. This is precisely the site of the slave tree and later its memorial.

The year 1826 therefore marks the first use of Church Square corner for the official sale of enslaved people. The late 1820s saw a rapid increase of slave people sold to settle sequestrations and insolvencies at that site. For example, in the course of 1827, 212 people were sold in this way according to the newspaper notifications. Among those sold in January 1827 on the Church Square corner on account of Carel Albrecht Haupt were:

- Pluto of Mosambique, Carolus of Mosambique,

- Africa of Matjava,

- Carolus of Macao, Dansmeester of the Cape,

- Subo of the Cape (all labourers and gardeners)

- Partie of the Cape, houseboy

- Pierre of the Cape, houseboy and musician

- Constable of Bougies, butcher (absconded)

- Marie of Mosambique with her child Martha of the Cape

- Marie of the Cape, sempstress with her children Louisa, Henry, David

and Robert - Pamela of the Cape with her child William

- and further a fifth share in the slaves Dolphina and her children Job, Christian, Regina, William, Salima and Maddelia.

The new Charter of Justice for the Cape saw the closing of the Sequestrator’s department to be replaced by the new Supreme Court officials termed sheriffs. By June 1828, regular notifications by the High Sheriff’s office of sales of slave people at its stores in Church Square had begun. In the period immediately before the emancipation of the slaves in 1834, the numbers of slave people sold on Church Square declined rapidly. In 1834, numbers seem limited to about four slave people sold, including the sale of Abraham to settle a case of debt brought by Jacob de Villiers against the “Malay Priest” Magadas. In the course of 1835, the year after emancipation, the sale of the rights to the services of apprentices became the new normal. About four such sales took place in that year, with sales disappearing altogether by the end of the year.

Memorialisation of the site and the tree

In August 1898 the Cape Times reported the death of John, proper name Joemat, who for 35 years had been a familiar figure on Church Square selling fruit and sweets. His stall had been underneath a tree, the so-called ‘Old Fir Tree’, on the pavement in front of Hilliard’s drapery on the corner with Spin Street. Born on 25 September 1804, “Old John” was described patronizingly as “one of the old slaves,” and “according to his story, he was bought and sold again on the same spot where he kept his stall for so many years in front of Mr Hilliard’s store.” It was this testimony of John/Joemat that initiated the process of memorialisation of the slave tree.

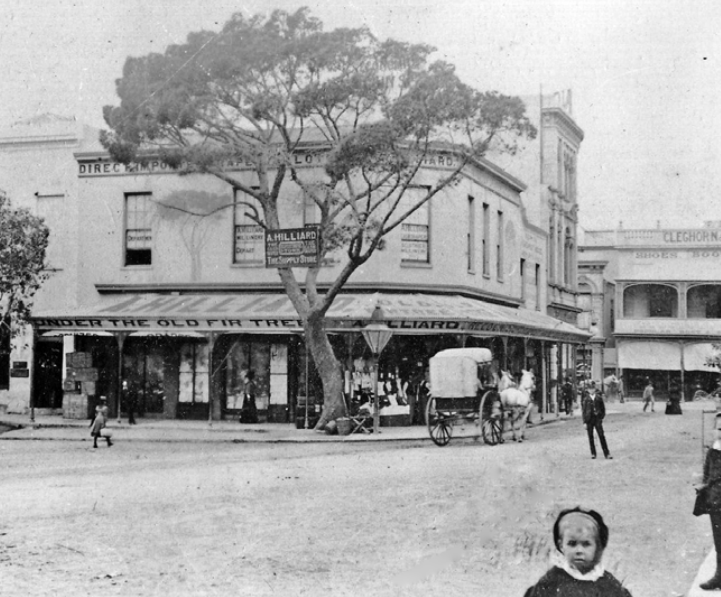

A photograph of Church Square depicts not only the large tree in front of Hilliard’s corner store under which Joemat sat but it also shows a little table beneath the tree which could well be his. The Sequestrator’s store is probably the building attached to Hilliard’s main building but fronting Church Square.

Church Square, ca. 1892, corner with Spin Street, showing Hilliard’s, the Slave Tree and perhaps Joemat’s table (WCARS, Photographic Collections)

In 1953 George Manuel, a journalist at the Cape Times, who had lived for much of his life in District Six, added further detail on Joemat:

There are still people in Cape Town who remember John Joemat, the wizened old Coloured man who for many years was as much a landmark on Church Square as the historic Fir Tree under which he had his fruit and sweet stall … Everyone knew and liked him in those friendly and leisurely days.

Manuel adds that Alfred Hilliard had in 1880 given Joemat permission to trade under the Fir Tree outside his linen and drapery shop, and that Joemat had had a strong affection for the storeowner.

There are no further confirmed personal or family details for Joemat other than that he was “Malay” and had sold koeksisters, a local Muslim speciality. According to records there are several slaves with this name. A Jumat April of Cross Street in District Six died on 27 August 1898 aged about 100.41 Several slaves called Joemat were sold in Church Square to settle debt, as for example, on 17 August 1827, Joemat, a coachman, the property of the merchant Fredrik Wilhelm Woeke. However, according to the Slave Office records, this Joemat was 43 years old in 1827. making him 114 years old in 1898 when John/Joemat of Church Square died. A family identification of Joemat, therefore, has not been possible. It is hoped that future slave and family research might yield a more complete identification of John/Joemat, who was sold and resold as a slave on Church Square.

The memorial

The slave tree under which Joemat sat near the corner with Spin Street and which was apparently in a very poor state, was cut down to a stump by the Cape Town City Council in November 1916.

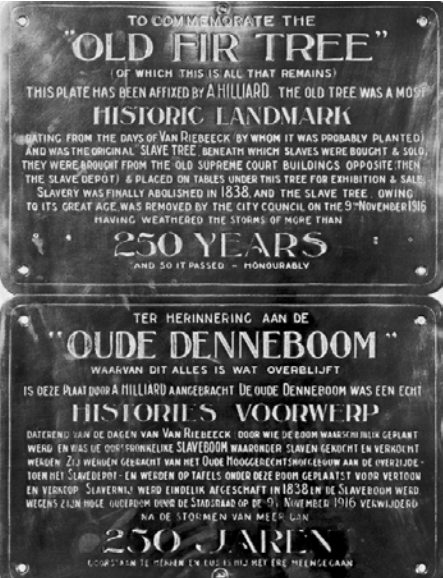

Bronze plaque attached to Slave Tree stump from ca.1916-ca.1951 (Iziko Social History Collections)

Some time soon afterwards, Alfred Hilliard spearheaded the project to manufacture the first plaque to commemorate the slave tree that reads:

To Commemorate the / “Old Fir Tree” of which this is all that remains / This Plate has been affixed by / A. Hilliard the Old Fir Tree was a most / Historic Landmark / the original Slave Tree beneath which slaves were / bought and sold. / They were placed on tables under this tree for exhibition & sale / Slavery was finally / abolished in 1838 and the Slave Tree owing to its great age was removed by the City Council on the 9th November 1916 / having weathered the storms of more than 250 Years /and so it passed honourably

Then, on 20 November 1951, the stump itself and the plaque were removed by the Council for purposes of widening Spin Street as an arterial to the central city.

Stump between two of Hilliard’s pillars (arrowed) (Possibly National Library of South Africa)

Several buildings were also demolished, including Hilliard’s on the corner of Spin Street and Church Square in front of which the stump had stood. The spot on which the old memorial had formerly been located found itself by 1953 in the middle of the widened Spin Street on the traffic island, and here a new memorial, sans tree stump, was constructed by the City authorities. This can be found there today.

Much discussion concerning the tree’s history, date and preservation preceded the removal of the stump and the bronze plaque attached to the stump.

The Cape Argus described the manoeuvre in graphic detail:

After a dozen City Council workmen had struggled with it for three hours, the old slave tree stump in Church Square was wrenched from its roots today … After the thick dry roots had been cut, it was levered out of the ground—like a huge, rotted tooth—and with much grunting and groaning from the dozen workmen finally loaded on to a lorry. It was taken to the South African Museum where after a clean up it will join the other exhibits … Patched together with cement the stump weighed half a ton.

Initially in 1950, after the stump of the tree had been vandalised, Keppel Barnard, Director of the South African Museum, declared dismissively, “We do not go in for that sort of historic monument. I do not think we could place it in this museum.” However, on 24 September 1951, Barnard changed his mind saying reluctantly that “he was prepared to take the stump and plaque if the council did not want it, but felt it would be more suited to a civic museum,” and on 22 October 1951 he wrote accepting the donation. A thick slice of the top of the stump and the plaque today forms part of the Social History Collections of Iziko Museums of South Africa.

A botanist, Edith Stephens, had campaigned with the Natural History Club for the stump’s preservation. She asked that she might do a dendrochronology test before the stump was removed and reported:

it is not more than 165 years old … It must have been planted about 1786—more than 130 years after Van Riebeeck came to the Cape … the plaque has been misleading the public all these years [by claiming that the tree dates to the days of Van Riebeeck].

However, sophisticated techniques will in the future have to confirm Edith Stephens’ data as to both the age and type of exotic pine. Stephens had also been given permission to test a branch/fork of the Old Slave Tree preserved in the City Council’s historical collections. This hadbeen donated to the Council in 1945 by the Administrator of the Cape, later Governor General, Gideon Brand van Zyl, who had for many years walked past the slave tree to his father’s legal practice in Church Square where he also worked. He was later chairman of the National Mutual Life Association of Australasia’s South African board, which likewise had offices in Church Square. Van Zyl paid for a plaque to accompany the branch which reads:

Presented by the Right Hon. G.B. van Zyl, P.C., to the Council of the City of Cape Town, being a portion of the original “Slave Tree” said to date from the days of van Riebeeck, and beneath which slaves were bought and sold. The original fir tree which stood in the present Church Square, was felled by the Council on the 9th November, 1916. 31.12.45.5

Stephens identified the branch as that of a stone pine, concluding that the annual rings show that the tree grew vigorously enough in its youth to have been sufficiently large to have been a focal point for sales before the abolition of slavery in 1834.

Branch of the Slave Tree and plaque, Cape Town City Council (City of Cape Town)

The plaque and fork/branch are in the City of Cape Town’s collection and are at present loaned to the District Six Museum in Buitenkant Street. In his “Reminiscences,” Van Zyl recorded:

At the corner of Spin Street and Church Square the stump of an old fir tree still stands. This was the tree under which slave auctions were held and when my father owned the corner block he permitted an old Malay ex-slave to sit there under a large umbrella and sell his goods, chiefly he sold koeisisters and did very well. When the tree died it was cut off 3 feet above ground and a plaque giving its history was placed on the stump. A part of a branch which I kept I gave to the City Council ...

In tracing the story of this memorialisation it is of special significance that the site’s importance was highlighted by Joemat, a former slave. While Hilliard participated in the process of memorialisation largely, it seems, as a means of branding his store, father and son Van Zyl were probably interested in promoting a sense of Cape colonial history going back to the time of Van Riebeeck.

Conclusion

Church Square was a site of many sales of slaves between 1826 and 1835 and it was natural that the sales were conducted in the shade of the nearest large tree. The Slave Tree memorial stands as a symbol for the thousands of enslaved people sold in the country districts, suburbs and in town before the emancipation of slaves in 1834 as well as after emancipation when their labour services as apprentices were sold. The memorial highlights the shared historical experiences of oppression and a determination to persevere, survive and celebrate. It should be an inspiration for those wishing to understand the past and to map out an equal society for the future. It is time to upgrade the memorial and make it a national site of remembrance.

Lalou Meltzer is the former Director of Social History at Iziko Museums of South Africa

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.