Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

I first met Lady Anne Barnard (1750- 1825) when she was in her mid forties. It was a brief encounter, in fact only a passage in the text of “The Table Mountain Book” by Jose Burman, that master storyteller of early South African travel. Lady Anne was reported to be the first European woman to climb to the top of Table Mountain (in July 1797) and I was resolved to find out more about her life and why a high born lady was living in Cape Town (Kaapsche Stad) at the end of the eighteenth century, during what became the first British Occupation (1795-1802).

Miniature portrait of Lady Anne Barnard nee Lindsay circa 1780 (Defiance - The Life and Choices of Lady Anne Barnard)

Lady Anne, at the age of 46, would accompany her husband Andrew Barnard (twelve years her junior) on a three month sea voyage to the Cape of Good Hope where he was sent as the Colonial Secretary, serving the first British Governor, Lord Macartney, arriving there in May 1797. Britain had deposed the “Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie” (VOC) at the Battle of Muizenberg (16/09/1795) and occupied the Cape to thwart the French from doing likewise. France’s revolutionary leaders had declared war on Britain, Holland and Spain in March of 1793, endeavouring to spread their revolutionary ideals even before Napoleon had risen to power. Consequent to events in Europe, the Cape could not avoid getting embroiled in a war where the two main belligerents were Britain and France (both competing to expand their trade and thus empires). The Cape was the halfway house between Europe and the Orient and both Table Bay and Simon’s Bay were used as anchorages by the fleets of several nations and not exclusively by the Dutch.

Lady Anne Barnard (nee Lindsay) resided in Cape Town for four and a half years (May 1797-January 1802) and has a special place in the history of the settlement of the Cape of Good Hope. Lady Macartney was unable to accompany her husband to the Cape and thus when the Governor took up his Office, he relied on Lady Anne to be his first lady and hostess, a role she was eminently suited for. The Cape had been run (since 1652) by the VOC as a replenishment station for its fleets of merchant ships on the long six month outward voyage from the island of Texel (Holland) to Batavia (Java) and their return journey back to Holland, thus on the British take over the population consisted of mostly Dutch speakers, whether employees of the VOC (colloquially called Jan Compagnie), free burgers, slaves or the indigenous Khoi Khoi.

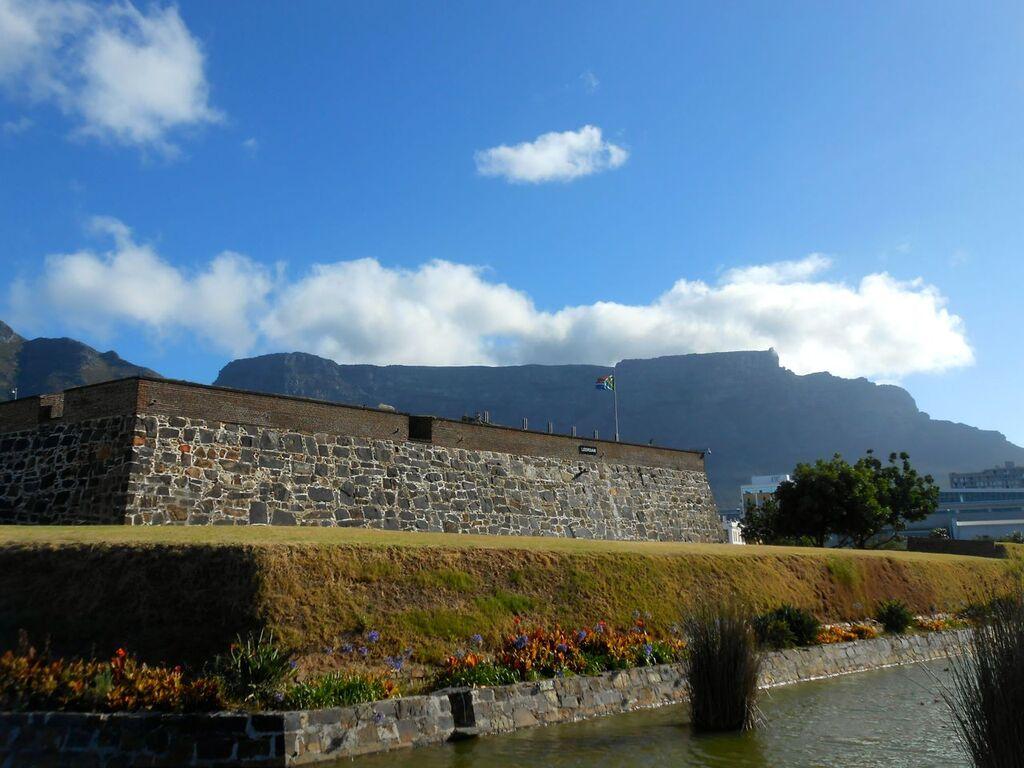

Lady Anne had many talents and was an accomplished musician, singer, painter and writer. Her letters of correspondence to Henry Dundas, the Minister for War and the Colonies give us valuable insight into what Cape Town must have been like 220 years ago; these are to be found in the book entitled South Africa a Century Ago: letters written from the Cape of Good Hope (1797-1801), first published in 1901. Not only do we have her writings but also her paintings (which hang in Cape Town Castle) which depict what she saw in Cape Town and its environs, for she was to travel as far as the Breede River to the East and Saldanha Bay to the north.

The Castle (The Heritage Portal)

Lady Anne was born into Scottish nobility on the 12th December 1750 at Balcarres House, in the East Neuk of Fife (north of the Firth of Forth), in sight on a clear day of Edinburgh across the Firth. She was the eldest child of the Fifth Earl of Balcarres, James Lindsay and his wife Anne (nee Dalrymple); she would have ten siblings, eight brothers and two sisters and when the last was born the Laird would be 74. Anne’s mother married the Laird, when he was 58 and she was only 22, this may well be the reason why Lady Anne would not accept proposals of marriage (20 in all) until she finally accepted Andrew Barnard’s when he was 30 and she 42. Their marriage at St. George’s, Hanover Square, London on 30th October 1793, was a simple affair for a few family members, she being given away by her youngest brother, Hugh and the ceremony being performed by another brother Charles. London Society was scathing over the marriage and Lady Anne was thought to have married below her station but as it happens their marriage proved to be a love match, not a common thing in Regency times.

Although Scottish by birth and upbringing, Lady Anne was more at home in London and she relocated there (along with her younger sister Margaret) from Edinburgh (then a five day journey by stage coach). Whilst still in her early twenties she became the darling of polite society due to her wit and charm at the dinner table and her singing and playing in the drawing room. She became friends with Mrs Maria Fitzherbert, a young widow, whom she later introduced to the Prince of Wales (later to become King George IV), the couple had a liaison which led them to secretly marry on 15th December 1785. The rub was that the bride was a Roman Catholic and under the Act of Settlement, 1689 he would forfeit the throne should he marry a Papist. More to the point the Royal Marriage Act, 1772 made any marriage illegal without the king’s consent, which would never be forthcoming (even if the king were mad, which King George III was). As it was the Prince would break off with Maria and reluctantly marry his cousin, Princess Caroline of Brunswick. When he died in 1833 a miniature portrait of Maria was to be found around his neck.

To say Lady Anne lived in interesting times would be no exaggeration as she witnessed great changes brought about by the Enlightenment, which in turn spawned the American and the French Revolutions and the rise of Great Britain as the major trading nation and sea power going into the 19th century, which in turn made the British take control of the Cape of Good Hope and as fate would have it bring Lady Anne to the southern tip of Africa, where she would spend her happiest days. She will always be remembered first and foremost for her time spent in South Africa as she set the scene for later generations (through her writings and paintings) of how life in the Cape was lived before the advent of our modern world.

Scroll down to the comments section to watch a wonderful insert on Lady Anne Barnard compiled by the team from Pasella.

References and further reading:

- “The Table Mountain Book” by Jose Burman, published by Human & Rousseau, 1991.

- “In the footsteps of Lady Anne Barnard” by Jose Burman, published by Human & Rousseau, 1990.

- “South Africa a century ago; letters written from the Cape of Good Hope (1797-1801)” by Lady Anne Barnard, Edited with a memoir & brief notes by W.H. Wilkins, published by Smith Elder & Co. 1910

- “Defiance, the Life and Choices of Lady Anne Barnard” by Stephen Taylor, published by Faber & Faber, 2015.

- “Wine, Women & Good Hope – a history of scandalous behaviour in the Cape” by June McKinnon, published by Penguin, 2015.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.