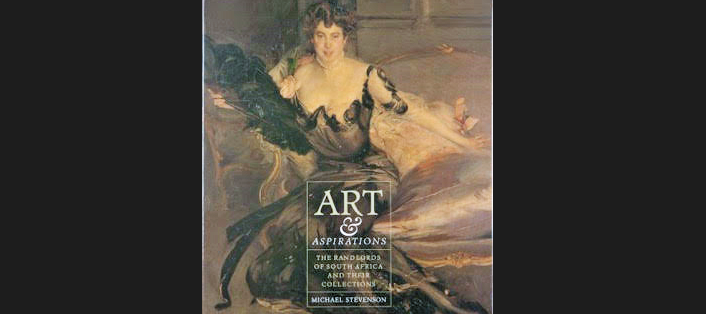

I turned to this book on my shelves because I sought some background information on the Hal Hurst full length portrait of the elegant Mrs José Dale Lace. This now almost iconic Johannesburg society portrait hangs in the drawing room of Northwards. The illustration of the portrait features on the contents page of the Stevenson book but despite its prominent position in the book, there is very little discussion about the background to the portrait or the artist Hal Hurst. I then tried for information about Miss Fairfax, the Rodin marble bust, a prize possession of the Johannesburg Art Gallery, but was again disappointed with no more than a caption and brief explanation.

Surely then, I had to read the Stevenson book to really absorb all the clearly rich other art history material.

José Dale Lace Portrait

Michael Stevenson is an art historian, scholar, gallery owner and dealer who has produced a number of important books. Art and Aspirations was the first of a number of books. The vast research captured in this first study led to the award of a PhD at the University of Cape Town in 1998. The book followed five years later. This lavish and very beautiful coffee table book was published by Fernwood Press in 2002. It is magnificently produced as a quality volume of art history. It is a glamorous book filled with splendid full coloured illustrations of the art assembled by just seven Randlords in five collections. The book has great visual appeal. It is unusual for scholarly research for a thesis to be given such stellar publishing treatment. Fernwood have established a reputation for fine books and in this case there is a list of the great and the good in South African business and academic circles who bought into the project and were rewarded with a highly collectible book (their names are included in a list of subscribers alongside the cartoon of Barney Barnato).

First impressions of this book are of a tantalizing mix of 19th century contemporary black and white photographs of the hubs of the South African industrial diamond facets, oil portraits of the Randlords and their wives, photographs and cartoons. For the architectural historian there are photos of the interiors and exteriors of their houses in Britain and South Africa and finally the many illustrations of the art works which are central to this study.

If you are a keen Africana collector, enjoy art history or are interested in the art collecting dimension of key figures in South Africa's mining past this is a "must own" title.

Of late the Randlords have not received a good press. History has not been kind to that amorphous group of immigrant entrepreneurs who came to South Africa in the wake of the diamond discoveries. They were the prominent millionaires who shaped the economy and politics of South Africa in the period 1880 to 1910. Most came from humble backgrounds from Britain and Germany (though J B Robinson was South African born). They deliberately strategized to make their fortunes and were the men who succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. Their wealth was built on mining enterprise, first in diamonds and later in gold. They were the owners of the mines and the financiers who bought and sold shares and sought to use their wealth to influence political events. They were the small group of men whose fortunes were made through share transactions, mine purchases and the flotation of the mining companies. The Randlords came to dominate the late 19th century economy. The current historical view is that their gains were ill gotten - grounded in exploitative practices in the recruitment of cheap labour and monopolistic and oligopolistic practices in diamonds and gold. They were capitalists of the worst type. They were a group who allied themselves with the politics and identity of British colonialism and did little for their adopted country. The "Rhodes must fall" campaign takes their moral high ground from this simplistic view of Rhodes and his ilk and his legacy. The institutions that benefited from the wealth and legacy of the Randlords and their successors, a century after the demise of most, seek to distance themselves from their financial foundations and benefactions.

Well, all of this is a caricature and historical analysis requires a much more nuanced and detailed study of the activities, lives and legacy of that relatively small group of successful mining capitalists who made their names and fortunes in South Africa before 1900. This book glosses over the making of wealth but is far more specific and detailed in the spending of wealth on art and the creation of art collection. Why did this group then move on to conspicuous consumption through the acquisition of European art?

Stevenson has given immortality to these selected Randlords by finding, cataloguing, studying and explaining how and why Sir Joseph Robinson, Sir Lionel and Lady Phillips, Sir Max Michaelis, Alfred and Sir Otto Beit and Sir Julius Wernher viewed art and created collections of old masters, Italian Renaissance paintings, and 18th century British society portraits. The spread of art collected made for diverse collections. The book is primarily about the homes, taste, style and artistic sensibilities and art collections of these specific collectors. How was newly acquired mining wealth spent on old art and what did the acquisition of high art do for the status of this select group of newly rich mining entrepreneurs are the central questions posed and answered by Stevenson. This is a study about the consumption patterns of these wealthy individuals who fulfilled their aspirations through the purchase of art and its display in their homes. The author argues that their purchases in the final decades of the nineteenth century preceded the interest by American collectors in the art market of London and Paris.

Stevenson is an art historian and so the least satisfactory chapter of the book is in fact the first chapter where he attempts to set the scene by ranging quite widely over the origins of the wealth and aspirations of the Randlords. To do this effectively one needs a working definition of the term Randlords, perhaps going back to Emden and Wheatcroft. Stevenson goes for the dramatic and the shock tactic, by juxtaposing a full page sepia toned photo of "a black worker with smuggled diamonds", set against the well-heeled affluence of the white mine owners. There are some interesting grainy gritty photos of the Kimberley diggings with some early photographs of the aspiring to wealth younger Jules Porges, Barney Barnato, Herman Eckstein, Frederich Eckstein and Charles Rudd hard at work making their fortunes on the veld. This chapter tells a narrative story where extracts from memoirs are followed by choice quotes from novels and literary sources. This takes the place of a structured economic analysis of the origins of the wealth and company transactions of the Randlords. It appears that Stevenson considers anyone who was successful through ventures in mining part of the ranks of "the Randlords". But as other historians have pointed out being a "Randlord" was about political coalescence as much as about wealth. For example, there is a debate about whether Sammy Marks and his partner Barnet Lewis were actually Randlords. On the other hand it is too much to expect an art historian to also be an economic historian.

However, once the author uses his deep expertise as an art historian to present the substance of his research he commands his subject and becomes convincing and fascinating in the coverage of the main collections and the people behind them, readily slipping from patron to purchaser to art advisors, agents, auction houses and dealers. The art world of London in the late 19th century was a complex market. All of these Randlords bought art for their English homes both in London and the counties.

The strength of the book lies in the five chapters on the principal collections. Stevenson asserts that JB Robinson and the Philipses acquired art works to assert a cultured metropolitan identity. Robinson's acquisitions bought over a short period of time, filled the picture gallery and reception rooms of his town house in London on Park Lane. When Robinson came to disposing of his art through Christies in 1923 he found parting from his art impossible and at least some of his collection came to Cape Town and can still be viewed at the home of the descendants at St James.

Sir Lionel Phillips and his wife Florence Phillips purchased Tynley Hall in Hampshire and they chose pictures which were "a joy to live with" rather than worry about cohesion in collecting. The decorative effect of the Gainsboroughs, the Constables and the Nattiers (their choice fell on British and French fashionable at the time, 18th century works) mattered in their London home at 33 Grosvenor Square and they sold their art works in 1906 when they returned to South Africa. Stevenson examined the longer term legacy of Florence Phillips and her campaign to collect, fund raise and create the Johannesburg Art Gallery, after 1909 drawing on the expertise of Hugh Lane in assembling the public collection. The relationship between patron and agent is particularly well handled and we are reminded that despite her involvement in many other art projects in South Africa, Florence Phillips is best remembered for her Johannesburg Art Gallery initiative. Max Michaelis is remembered as the man who benefitted Johannesburg with its library of art books, and also for assembling the collection of old Dutch masters, given to South Africa and exhibited in the Old Tuin Huis in Cape Town. There is a fascinating analysis of what this bequest meant for South African and in particular Afrikaner identity, but the gift to Cape Town generated huge acrimony. There was a link too between public benefaction and the award of British titles (or should that be "reward").

Johannesburg Art Gallery (The Heritage Portal)

The most interesting question for anyone assembling any collection whether paintings, books or objects, is what happens to a collection after death. We are after all only custodians and curators of treasures. The final postscript concludes with regret that the Randlord collections ended fragmented and scattered among descendants, none remaining intact. It was only Rhodes' home Groote Schuur which was bequeathed with its contents to the State and there were very few art works. In contrast one looks to international examples such as the Huntingdon Library and European art collection preserved together with their gardens on the Huntington Estate in Pasadena California. But in fact here ownership resides with a Trust which restricts public admission via limited opening hours and a high ticket price (other than on a sponsored once a month open to all free day). Stevenson's conclusion is that the Randlords, individually or collectively should have established a national art gallery for South Africa and that the Johannesburg Art Gallery did not go far enough. We need to remind ourselves that tastes change and both the collecting interests and the viewing interests of new elites and gallery visitors concentrate on art by South African artists. European art tends now to be consigned to colonial categories and if you wish to see such art your best option is to travel to European and American cities. Florence Phillips was the only one of the Randlords who included African generated art in her collecting endeavors.

2016 Price Guide: Surprisingly this title is still readily available and for example can be purchased from Quagga Books in Kalk Bay for R420 or from Clarke's bookshop (of course if you turn to Antiquarian Auctions or to Amazon expect to pay well over $130). If you have not yet bought a copy, it is a strongly recommended title to be added to your wants list and is a most inexpensive title in South Africa, in contrast to far less impressive books on African art.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.